I’ve spent a lot of this winter in Tripoli, with my mother. One afternoon she comes back home from an outing with some friends, and says, “Sometimes, all you need is a walk down the street with people you like.” My mother is like that, poetic and wise, and I’m often transcribing—or stealing—her sentences.

Over the past fourteen years she’s lived in Tripoli, my mother has made some very close friends. Her friends are at different stages of life; some, like her, are in their fifties with adult children living their own separate lives; others, in their thirties, have children still in school.

My mother, who was not able to complete her law degree in her twenties, returned to the Lebanese University’s Faculty of Law only a couple of years ago. Inspired by each other, her friends have either completed or are completing their degrees in philosophy, nutrition, civil engineering and sociology. Some Sundays they drink coffee by the sea in Mina or have lunch at one of the cafes in Dam wel-Farez. They have a lot in common: they’re funny and fierce, hardworking, generous.

But I suppose the uniting force behind their close friendship is the simple fact that they are Syrian women in Tripoli—specifically, Syrian women in Tripoli married to Lebanese men.

***

In 2019, UNDP commissioned a report as part of its conflict analysis series. Written by researcher Bilal Ayoubi, it investigates intermarriage between Syrians and Lebanese in two areas in northern Lebanon: Tleil, a village in Akkar, and Qobbe, a neighbourhood in Tripoli. Though both areas host a substantial number of Syrian refugees, Ayoubi finds that intermarriages are much more common (or at least more spoken about) in Qobbe than in Tleil. Most Lebanese respondents, in both areas, were generally uncomfortable with the idea of intermarriage. Only a few interviewees thought them positive or likely to improve community relationships. This is concurred with a 2013 survey by FAFO, which finds that around 82% of Lebanese respondents are uncomfortable with the idea of someone in their family marrying a Syrian.

One of my first research projects, in 2018, was on ‘social cohesion’ among Syrian refugees and Lebanese host communities. It was a large-scale project and I had to conduct over a hundred interviews and focus groups with municipalities, community members (both Syrian and Lebanese), activists and NGOs.

After most discussions, I would head home with a bitter taste I couldn’t wash down. I thought I had understood racism towards Syrian refugees, the politics of scapegoating. But the interviews and focus groups forced me to confront the pulsing anger, the hatred even, which existed or which had come to exist between Lebanese and Syrians. For many Lebanese women I interviewed, Syrian women were a threat: they populated their towns and cities, gave birth too much, and were uneducated.

Such perceptions exist across Lebanon to varying degrees, and are expressed through sets of codes and mannerisms which depend on several factors: the sectarian and socioeconomic leanings of an area, its political history and class dynamics, the history of Syrian agricultural labour in the area, and geographic location (including degree of urbanisation and proximity to the Syrian borders). I tried to take note of areas more accepting of Syrian refugees, and the reasons for it: as is often the case in qualitative research, mixed findings and outliers dominated, but despite this there was something quite exceptional – as there usually is – about Tripoli.

Several studies have found that Syrian refugees often prefer to live in Tripoli because of established links between Syria and Lebanon, especially those between the cities of Homs and Tripoli. Both cities are majority Sunni, and have relatively conservative social norms. Since transnational marriages between Lebanese and Syrians from those areas have historically been common, it was natural for Lebanese in-laws to facilitate the arrival of Syrians after 2011, and it was for this reason that many from my mother’s family moved to Tripoli. And although the city has long been considered unsafe—largely because of its history of armed clashes and bouts of Sunni fundamentalism—Syrian refugees tend to prefer it to other areas, perceiving it as safe for them.

Several studies have found that Syrian refugees often prefer to live in Tripoli because of established links between Syria and Lebanon, especially those between the cities of Homs and Tripoli. Both cities are majority Sunni, and have relatively conservative social norms. Since transnational marriages between Lebanese and Syrians from those areas have historically been common, it was natural for Lebanese in-laws to facilitate the arrival of Syrians after 2011, and it was for this reason that many from my mother’s family moved to Tripoli. And although the city has long been considered unsafe—largely because of its history of armed clashes and bouts of Sunni fundamentalism—Syrian refugees tend to prefer it to other areas, perceiving it as safe for them.

***

“It was only after moving to Tripoli that I actually felt I carried the Lebanese passport,” Zeina*, one of my mother’s friends, tells me. Zeina is originally from Damascus and, like my mother, is married to a Lebanese man from north Lebanon. At first she lived with her husband in Akkar. There, she says, she faced significant racism – especially from Christian villagers unable to overlook her Syrianness. They disapproved of how much Arabic she spoke, expecting her to incorporate more French, or English, into her everyday language. This concurs with Ayoubi’s study, which finds that Lebanese people in Tleil, a Christian-majority village, are averse to the idea of intermarriage in part because they are wary of demographic shifts as well as cultural dissonances.

When Zeina’s family moved to Tripoli, this changed in an almost radical way. Zeina, who is now in Europe with her family, continues, “My years in Tripoli were among the best of my life.”

Most of my mother’s friends feel this way. Yara*, for instance, has now lived in Tripoli for almost as long as she lived in Aleppo. “Of course I feel a sense of belonging to Tripoli,” she says. “It’s been home to me, and my family, for years now.”

Diana* has also had a longstanding relationship with Tripoli: she finished her undergraduate at the city’s Lebanese University branch, and even when she lived in Talkalakh, the village in Syria she (and my mother) grew up in, she would often visit her aunties in Tripoli. “I’ve been coming to Tripoli since I was a little girl,” she tells me. Diana hasn’t had to think of whether Tripoli feels like a home, because it has naturally always been one.

Not everyone’s feelings are so uncomplicated. “My relationship with Tripoli changes everyday,” says Rana*, a relative newcomer to the city. “I continue to feel like a guest here–so, I choose to show it my best face, and it shows me its best face too.”

***

Identities are constructed and imagined, then reconstructed and reimagined time and time again. Tripoli was long known as Tarablus el-Sham (Tripoli of the Levant, or Tripoli of Damascus) to distinguish it from the capital city of Libya. In many ways, the city’s complex history, at least its more modern one, is a reflection of its complex relationship with Syria.

In 1520, the Ottomans split the Levant into three vilayets: Aleppo, Damascus, and Tripoli. The latter extended from Byblos to Tartous, and included the towns of Homs and Hama. British traveller, John Carne, noted three centuries later, in 1820, that “Tripoli is the best looking town in Syria, the houses being built of stone.” A century after him, the French mandate would carve out a Lebanon and a Syria in 1920, rupturing a more or less organic relationship between Tripoli and its Syrian counterparts. In the century that followed, Lebanon has had to confront its fragmented and militant sectarian identities while Syria has had to confront its bloody, authoritarian one. The 1960 book by John Gulick, “Tripoli: A Modern Arab City”, argues that many Tripolitans had always felt they “rightfully belonged to Syria.”

The civil war in Lebanon and the Syrian occupation have had horrific consequences on Tripoli (and the rest of the country). During those years, the Syrian regime entrenched the divide between the city’s communities—between Sunnis, Christians, and Alawites, as well as among Sunnis themselves. In a paper on Sunni Islamism in Tripoli and the Assad regime, Tine Gade argues that “the Syrian presence created alliances, conflicts and divisions still present in Tripoli today.”

For decades, the Sunni-Alawite divide within the city has been instrumentalised by political parties especially in the Syrian-backed Jabal Mohsen and anti-Syrian regime Bab el-Tebbaneh—two of the most impoverished and ostracised neighbourhoods in the country, ironically separated by the bullet-ridden Syria Street.

I don’t think any other city in Lebanon responded more passionately than Tripoli to the Syrian revolution in 2011 and 2012. Alex Simmons, in an article on Tripoli’s revolving stalemate, writes, “The Syrian uprising sparked intense solidarity on the streets of Tripoli, which holds closer historic ties to Homs and Hama than to Beirut, and still nurses bitter memories of the regime in Damascus.” And perhaps no other city was as polarised by the war that followed. It intensified the grievances of the Sunni community, and it made palpable the profound distrust towards Lebanon’s security apparatuses. Intermittent suicide bombings and armed clashes persisted in the city, closely following the pro-regime, anti-regime, and Islamist divisions within Syria. Meanwhile, thousands of Syrian refugees arrived in Tripoli and have continued to arrive since 2011, often settling into the city’s most impoverished neighbourhoods.

After over a decade of a severe, protracted refugee crisis in Lebanon, the distrust, anger, fear and disillusionment have only expanded and taken on new faces. A recent study on the urban displacement of Syrians in Tripoli describes them as ‘in limbo’, with living conditions having deteriorated over the years. The study quotes a Syrian respondent as saying, “Each year is worse than the previous year. When I first arrived, there was more freedom, [it was] more comfortable. Now, day by day, it is getting worse and worse than before.”

For recent studies I conducted for the UN Women and Lebanese Reforestation Initiative, I interviewed dozens of families in Tripoli, many of whom expressed growing anxiety and animosity towards Syrians. One Lebanese man told me, “We welcomed them in, yes, but now that our situation [as Lebanese people] is getting harder and harder, what do we do with them?”

***

Not too long ago Diana was at the library, buying school books for her children. After Diana asked her a question, the librarian laughed cruelly and asked, “Oh, you’re Syrian?”

“Yes.”

“So, are you a refugee? Why are you here?”

Diana told her she had been living in Lebanon for over a decade now, and that her husband was Lebanese.

“All these years here,” the librarian said, “And you haven’t changed your language?”

“You mean… my accent?” Diana quipped back.

No matter how accepting Tripoli might be, my mother and her friends say there are often lingering questions and unspoken judgments once their vowels are uttered. “My accent follows me everywhere,” Zeina says. This is something I have noticed with my mother: once Lebanese people establish that she is Syrian, they often follow up with, “Oh, but you don’t look Syrian.”

For many Lebanese, whether in Tripoli or outside, there is a desire to distinguish between refugees and Syrians who lived in Lebanon before 2011. Diana elaborates, “When people meet me, they immediately want to know—when did I come to the country? Before or after 2011?” Yara adds that this question is asked to suss out what ‘type’ of Syrian she is.

This is where the difference lies, of course. My mother and her friends are able to negotiate with the city, to find their footing in it, because they are middle-class Syrian women, married to Lebanese men, and were in Tripoli before the war. They somehow deserve to belong, unlike other Syrian women.

***

My mother’s relationship with the city is intimate. She circles the Rachid Karami International Fair for evening walks, picks out pomelos and figs from the city’s cartsellers on her way home. She doesn’t know all the names of the city’s dwellers–the shopkeepers and cartsellers and neighbours—but she misses them when she’s away, and they miss her, too.

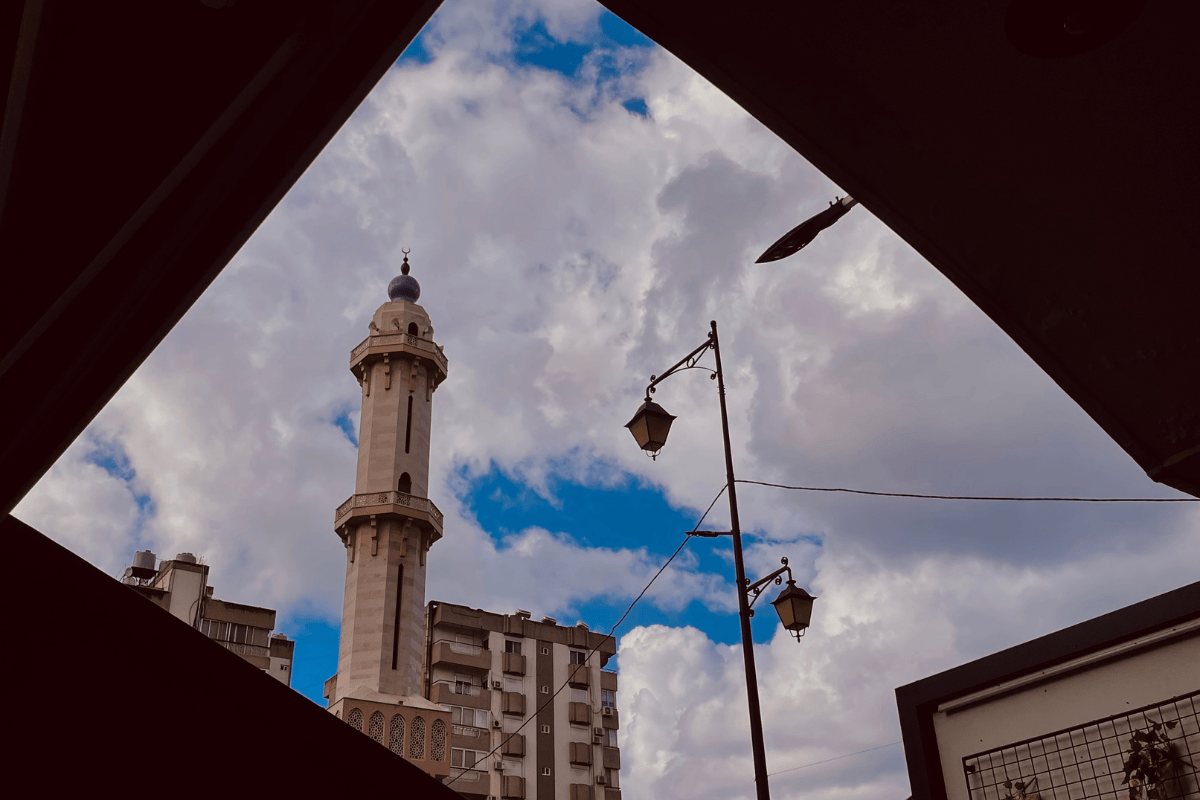

Her friends also have their own personal versions of Tripoli. The perfume shops in Nadim el-Jisr; the citrus boulevards lining Riad el-Solh. Sahlab and habayeb (a dessert made from wheat-grain, chickpeas and orange-blossom water) from El Masri when it rains. Poetry readings at Safadi Centre, and coffee after in Mina. Ice-cream—for the kids, and the mothers—in the summer, during road trips to Ammoua Forest in Akkar and Oyoun el-Samak in Donniyeh. The sound of one mosque chanting over another. Their friendships, with each other, but also with Lebanese people—those they study, work, laugh, and share the city with.

Her friends also have their own personal versions of Tripoli. The perfume shops in Nadim el-Jisr; the citrus boulevards lining Riad el-Solh. Sahlab and habayeb (a dessert made from wheat-grain, chickpeas and orange-blossom water) from El Masri when it rains. Poetry readings at Safadi Centre, and coffee after in Mina. Ice-cream—for the kids, and the mothers—in the summer, during road trips to Ammoua Forest in Akkar and Oyoun el-Samak in Donniyeh. The sound of one mosque chanting over another. Their friendships, with each other, but also with Lebanese people—those they study, work, laugh, and share the city with.

***

Tripoli was given the moniker ‘The Bride of The Revolution’ during the October 2019 protests. If a bride is supposed to be tenacious and resolute, with a repressed anger that needs to explode, then it’s a fitting title for the city during that historical moment. The term personally annoyed me—not only because it was trite, but because it expressed a romanticised fascination with Tripoli. For many, it was shocking that Tripoli could be the epicentre of the October protests. In reality, the city has never been as homogenous or static as people make it out to be: it is a midpoint between geographies, a cultural archive of many histories, a potpourri of political and social and economic identities.

When people find out I have lived in Tripoli, or that my family’s base remains there, they assume that at least one of my parents is a Tripolitan. But neither of them grew up there, or had any sort of attachment to the city. In fact, the only reason we moved there is because it offered many possibilities in terms of schooling and community-building. It was also close to Talkalakh, the Syrian village my grandparents had lived in before the war. Tripoli became the midpoint between a potential future for my brothers and me in Beirut, and a dissolving past of our lives in Talkalakh.

***

The drive from Tripoli to Talkalakh, I remember, was quite short. As a child it was not clear to me where Lebanon began and Syria ended—in my head, it was one long road with the same trees.

Today, when I speak to Zeina, Diana, Rana and Yara, they all say their relationship to Syria has fundamentally changed. For some, the continued dominance of the Assad regime has damaged their relationship with the country beyond repair.

“Where my parents are is where I belong,” Yara says. “It’s not a matter of land or house, it’s a matter of people.” For Rana, her relationship is no longer to the cities she grew up in, but rather their inhabitants. “My relationship to Syria is in my relationship to its people, and not the actual space itself.”

Yara adds, “Seeing what happened to my parents, to my loved ones, to every Syrian, makes me not want to attach myself to any place. If at any moment, someone can lose it all – what is the point, really?”

***

In April 2022, an overloaded boat sank off the coast of Tripoli. The boat was carrying over 80 Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian passengers. Survivors of this tragedy say Lebanon’s naval forces rammed the boat more than once.

This dangerous and desperate journey, from Tripoli to Europe, has become growingly common. Tripoli has long been considered the poorest city in Lebanon, arguably even in the Mediterranean, and the economic and political situation is unbearable for many.

It is this socio-economic background which we must bear in mind when considering the lived and perceived grievances that working class and middle-class Lebanese people feel, especially in historically neglected areas. All of this is compounded by the (unfortunate) inability of many Lebanese to distinguish between the Syrian regime (and its long oppressive history in their country) and the Syrian people; the population strain and limited access to resources; and the populist media narratives used, over and over again, by political parties across the board to incite local communities against each other. A thorough understanding of this intricate topic would take countless more interviews and focus groups, and no small amount of humility, and is sadly beyond the scope of this article.

***

Adrienne Rich, another poet whose lines I often steal, writes, in her poem ‘What Kind of Times Are These’:

“There’s a place between two stands of trees where the grass grows uphill […]

this isn’t a Russian poem, this is not somewhere else but here,

our country moving closer to its own truth and dread,

its own ways of making people disappear.”

As I read and re-read this poem, I greedily consider it a depiction of Lebanon and Syria—their sombre and disappearing histories, the recklessness of trees on concrete borders. Rich, in this poem, is responding to Bertolt Brecht who, in the 1930s, wrote, “What times are these, in which / A conversation about trees is almost a crime!” How dare we talk about beauty, Brecht wonders, when we live with such horror? A century later, Rich reminds us: “in times like these / to have you listen at all, it’s necessary / to talk about trees.” Those same trees, that same sea. The image is blinding in its simplicity: our peoples may continue to love and hate one another, but I suppose, in order to do that better, and more effectively, we must ‘move closer to our truth and our dread’, to what separates us and, more importantly, what does not.