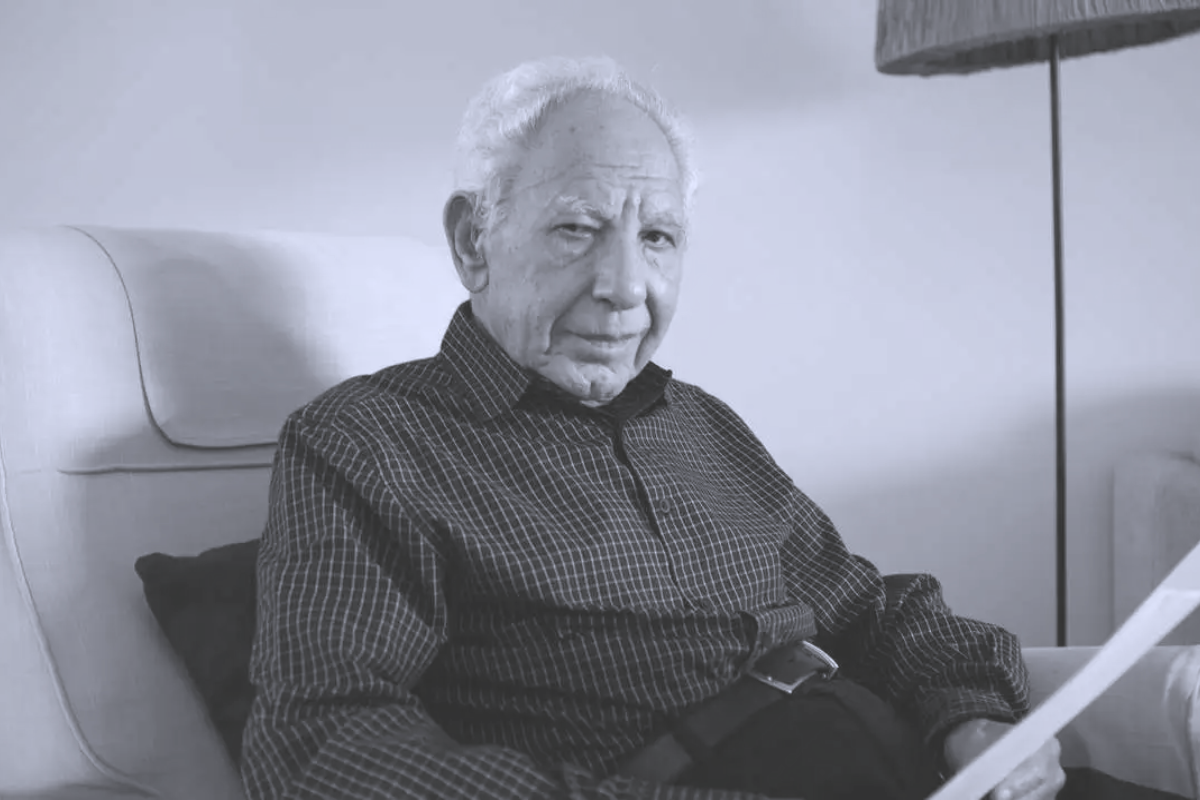

There is no better phrase to describe Riad al-Turk, who departed our world on Monday, than the French expression animale politique, a ‘political animal’. The French expression is commonly used to praise and appreciate the political competencies of certain leaders; it encompasses the principles of dedicating one’s life to politics, commitment to serving a public cause, stubbornness and perseverance, and the distinguishing of politics from other neighbouring fields such as ideology, religion, community and society, in a way that Riad himself once summarised in 2005 with the phrase ‘payment on receipt’. What he meant at the time was that the opposition should not make any concessions to the regime without securing something concrete in return. This man lived most of his life in a society deprived of political life, with scant benefit to the potential political credentials of its residents, all because of one deified despot who put Riad al-Turk in prison for seventeen years and eight months between 1980 and 1998, whose son then imprisoned him for 15 months between the beginning of September 2001 and mid-November 2002.

After his second release from prison, when he was seventy-two years old and enjoyed widespread popularity, many suggested that he leave direct party work and that his role should shift to some sort of trans-party national authority, one independent of the existing political parties. Riad al-Turk, who was good at listening and then ignoring, listened and ignored. I believe that behind this lay the instinct of the ‘political animal’ who realised that politics was first and foremost a balance of power, and that without organisation there would be no hope of influencing these balances. At that time, in interviews and in his lecture at the Atassi Forum on August 5, 2001, he spoke about the balance of weakness between the regime and the opposition. He knew the opposition and its weaknesses well, but he estimated that the regime was just as frail. However, the scales of the opposition were not weighing down, what was less dysfunctional became more dysfunctional, and the efforts to build an opposition bloc that was both balanced and radical did not succeed. Perhaps Riad al-Turk did not make things easy for some potential partners – and the reason for this was not exclusively that these partners could not tolerate the adversity that he was experienced in enduring.

Riad al-Turk lived a life of struggle and dedication without ever expecting a reward. He wanted to change Syria democratically, but he did not succeed. Perhaps what hurt him the most was that he had to leave the country in 2018, when he was 88. He left so as not to die cooped up inside, causing troubles for his comrades with his death just as he had caused in his life. The man whose life partner, Asmaa al-Faisal, died that same year while in the care of their daughter Nisreen in Canada, died in the care of their second daughter, Khuzama, near Paris. The two daughters were children when their father was arrested in 1980.

Riad al-Turk was arrested in 1959 during the days of political union between Syria and Egypt, and was subjected to extraordinary torture, as a result of which he lost his hearing and almost lost his life. In fact, a rumor spread at the time that he had died; this was after his comrade Farajallah el-Helou had been killed by torture in the same period, which forced the union’s regime to show him live on television to deny the rumour of his death. Riad al-Turk would later say that everything he lived after that, that is, everything after the age of 29, was too old.

After the defeat of June 1967, al-Turk was among the Syrian communists who supported Palestinian and Arab guerrilla action against Israeli colonialism, displayed an independent attitude towards the Soviet Union, and showed Arab nationalist tendencies, at a time when this meant a closer relationship to the political, and defining oneself more with the political than the ideological. When the Syrian Communist Party split in 1972, the majority of the members of the Political Bureau (5 out of 7) and a significant bloc, perhaps the largest of the organisation, were against the bloc of Secretary-General Khalid Bakdash. The latter took the initiative, along with the other member of the Political Bureau, Youssef Faisal, to issue a statement on April 3, 1972, in which he spoke of an “adventurous, opportunistic revisionist clique” led by Riad al-Turk. Al-Turk was at the head of this relatively large, incohesive bloc, and after a few months, three of the five members of the Political Bureau returned to the original Soviet-backed party, but not before the name ‘Syrian Communist Party – Political Bureau’ stuck to this revisionist party.

Opposition to the regime was not a controversial issue at the time, and the party’s fourth conference in 1974 was still talking about a progressive nationalist regime. Only after the Syrian intervention in Lebanon in 1976 did the party transform into an increasingly radical opposition to the regime and become conscious of itself as a democratic opposition. Here we come across a political transformation represented by an increasingly powerful dictatorship that had been ruling the country for 6 years at that time; a period that, despite its brevity by today’s standards, remains the longest continuous period of rule for a Syrian president after independence. In my view, it coincided with a geopolitical shift, represented by the Hafez al-Assad regime installing its defence lines outside the country (namely, in Lebanon) and its inclusion in the Middle Eastern regional structure as a reliable dictatorship that fulfilled its international obligations. As Minister of Defense before 1970, Hafez al-Assad had prevented any armed Palestinian resistance from the Syrian front, despite the occupation of Quneitra and the Golan Heights and despite the presence of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees in the country. Therefore, the Palestinian armed resistance moved after Jordan to Lebanon, whose land Israel was not occupying, and not to the closest country, Syria.

The slogan of the Communist Party – Political Bureau was: “Liberation, Popular Democracy, Scientific Socialism, Arab Unity,” but after the Fifth Congress in 1979 it became “Liberation, Democracy, Socialism, Arab Unity,” which indicates a combination of the autonomous tendencies and the decline of the ideological determinant in defining the party. The issue of democracy has become central in defining the party and distinguishing its policy. However, the name of the party’s bulletin remained Nidal ash-Sha’b (The People’s Struggle), which was the name of the bulletin of the Syrian Communist Party before the split, along with the symbol of a hammer and sickle, and the slogan “Workers and oppressed peoples, unite!” It is the modified (or “revised”) Leninist version of the Marxist slogan, “Workers of the world, unite!” This shows that the party was still communist, but at the same time was changing. He continued to struggle for communist legitimacy for many years after that.

But perhaps due to the formative experience – that is, the split – the Communist Party – Political Bureau inherited a strong schismatic predisposition that was repeated several times, perhaps fueled by Riad al-Turk’s solid and uncompromising personality. A year after this conference, most of the party’s members were arrested, including the first secretary of its central committee, Riad al-Turk himself, and he would once again be subjected to brutal torture, which was nonetheless “nothing” compared to his torture during the period of the Unity regime, as he himself said to Muhammad Ali al-Atassi and Lubna Haddad in the film Ibn el-Amm (The Cousin). He was the only communist detainee who was not referred to the Supreme State Security Court in 1992, and he remained confined to a single cell in the Military Investigation Branch until his release from prison in 1998. He was described as a prisoner on behalf of the palace, i.e. a personal prisoner of Hafez al-Assad himself. He was released with the intervention of French President Jacques Chirac, who talked about him during a visit by the Syrian despot to Paris at the time. Al-Turk’s case was an item which French human rights and political bodies were able to include on that visit’s schedule. During his time in Paris, French newspaper correspondents met Hafez al-Assad and asked him about Riad al-Turk; he replied that al-Turk’s communist comrades had expelled him from their party, and that these comrades were regime-supporters (and the second half of the sentence is true, and it remained true after Khalid Bakdash’s party split and another party led by Youssef Faisal himself emerged from it; the two parties form part of the regime’s dysfunctional National Progressive Front to this day.) This was the same interview in which Hafez al-Assad denied that he was preparing his son, Bashar, to succeed him. Every Syrian knew that Bashar would be his father’s heir: only the father did not know!

Incidentally, I heard from Riad al-Turk personally that he met Hafez al-Assad once in 1974, and one of the things he said to him was: “We’ve thrown off our shackles!” Hafez al-Assad responded to him, “You will not completely throw off your shackles until you are fully independent from Moscow!”

After his release from prison, Riad immediately returned to political work, as befits such a political animal. He wanted to rebuild his party and reinvigorate the opposition to a degree that caused the late Jamal al-Atassi, who was at the head of the National Democratic Rally – the opposition political alliance, founded in 1979 and “lying in wait” since 1980 – to fear the daring of his friend, who was nearly seventy at the time. After almost two years, and a month or so before Hafez al-Assad, Jamal al-Atassi passed away. His memorial service took place in the Al-Sham Hotel movie theatre and was attended by Mustafa Tlass, the long-time Minister of Defense at the time. Riad al-Turk did not speak at the memorial. The spokesman for the National Democratic Rally, Hassan Abdul Azim, spoke and thanked General Mustafa Tlass for attending the ceremony. Riad left the hall angrily, wondering aloud: “What does this worthless person have to be thanked for?”

At the time of Bashar’s succession, Riad al-Turk stated in an interview that he would not vote for him, and that Bashar did not need his vote. In his lecture (which Al-Jumhuriya republished yesterday), he presented a plan for national reconciliation which might have spared the country much of its later tribulations, had it not been for the selfishness of the Assad regime and its lack of loyalty to the country.

In 2005, the Communist Party – Political Bureau clandestinely held a conference in which it changed its name to the Syrian Democratic People’s Party. Perhaps there has been insufficient discussion about this change; and perhaps in doing so the Democratic People’s Party displayed an intellectual atrophy, something the general intellectual atrophy of the non-Islamic Syrian opposition (as well as the Islamic one) did nothing to alleviate. On the contrary, the transformation required greater activation of the intellectual front. At seventy-five years old, Riad al-Turk was not now the first secretary of the new party, but he was practically its centre of gravity. This, coupled with an inherent schismatic predisposition, led to crises that could have been avoided. Riad al-Turk personally embodied the political continuity between the Communist Party – Political Bureau and the Democratic People’s Party, and the latter’s inheritance of the former. This was unfair to him, to the two parties, and to his old comrades, most of whom distanced themselves from both parties with varying degrees of bitterness.

Before the revolution, Riad al-Turk, with his aptitude for pithiness, said that Syria could not remain a “kingdom of silence”. When the Syrian revolution began, the octogenarian was part of it from the beginning and throughout.

Though it appears that the ranks of the Democratic People’s Party expanded at the beginning of the revolution, its expansion was limited by its rigid organisational and psycho-political structure.

On October 7, 2013, the regime arrested one of the leaders of the Syrian Democratic People’s Party, Fa’eq al-Mir, whose fate is still unknown to this day. In Fa’eq, various facets of the Democratic People’s Party were condensed: its radicalism, its popular spirit, and its tragic constitution with its precarious combination of idealism and realism, made even more precarious by the inhuman political conditions in the country and the region.

With the departure of “the cousin”, as he was affectionately nicknamed, against the backdrop of long years of Syrian tragedy, the division of the country, and a world whose desperation and extremism has culminated in what Gaza has been witnessing for nearly three months, the phrase “We have thrown off our shackles!” can be a promise to ourselves to continue the struggle that Riad al-Turk dedicated his life to, and a declaration of our determination not to let any power whatsoever fold us under its arm.