My friend and I have a strange ritual – once in a while we call and ask each other whether the regime will fall. Sometimes it’s the Assad regime, and sometimes it’s Putin, and today it’s the Israeli occupation and the global regime of oppression that underpins it. The collapse seems imminent yet impossible to imagine. Why?

The delusion that Palestinians and Palestinian resistance can be erased or forgotten has become accepted as real by Israeli settlers and their international allies. The Israeli security intelligence apparatus was genuinely convinced that Hamas was solely focused on securing economic welfare and its political goals within Gaza, and had abandoned the idea of the resistance and liberation of Palestine. They have come to believe the false reality that they themselves have carefully crafted: that Palestinian resistance is a forgotten and abandoned cause, that Israel can sustain its illegal existence indefinitely because it has the military upper hand. The news of normalisation with Arab states both contributed to this sense of the occupation becoming the permanent norm, and was the product of its development. As citizens and politicians implemented the occupation regime, its paradox evident through the simultaneous use of language such as “second Nakba” and Israel’s “right to exist and defend itself”, it wasn’t clear which version of reality they really believed in. Israeli settlers bought this idea too: that in return for their support, whether explicit or tacit, and the contribution of their bodies to the “demographic majority”, they would be protected and would be victorious.

On the surface of normalisation, there seemed to be a quid pro quo logic. The UAE, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco were expected to be given access to lucrative trade deals, exclusive defence contracts and security cooperation, as well as political benefits. These security and economic privileges are in a domain where only the ruling class gets to benefit from them, especially the military and security cooperation used to surveil its citizens. It could not be more obvious that the most tangible result of this normalisation has turned out to be discreditation of these countries’ governments in the eyes of the majority of their citizens. Juxtaposed with Palestinian suffering, the very idea that anything about Israeli occupation is “normal” seems surreal, as if belonging to an alternate reality. Parallel to normalisation with Israel, some of the same countries have normalised with the Syrian government. This is no coincidence. Current events in Palestine demonstrate that the dysfunctional systems propped up by some politicians and citizens today are not just the Israeli and Syrian regimes, but an entire regional and global order of racialized capitalism and neo-colonialism. The capitalist project is based on catastrophic hubris of infinite economic growth at any cost on a planet with limited resources. An order built on false belief is fragile. It opens itself up to threats that are ignored and erased by its imaginary reality.

Yassin al-Haj Saleh writes that normalisation with the Assad regime is baseless from a rational point of view, and that the explanation lies in the field of the irrational, an extremely common ideal shared more and more by the Arab “elites”: politics without politics, rights, debate or even society. This ideal consists of a purely material modernity: guarded havens for the oligarchs and semi-slavery conditions for the majority, exemplified in MBS’s NEOM and its “Line”, and the New Administrative Capital in Egypt. This is the exact same utopia offered to Jewish citizens of Israel. There are uncanny similarities between the language and symbolism deployed to make this idea not only normal but appealing, through media such as travel vlogs from Syria, the artificial environment of the Tel Aviv beach promenade and Dubai skyscrapers and malls, that obscure the absurd violence they rely on. Such fragile luxuries are not sustainable at their human cost. Popular protests in support of Palestine show that people all around the planet see, on a global scale, the connection between these marketed fabrications and the high fences and barbed wire keeping them out.

Normalisation with the Syrian regime means that its participants accept the notion there is no alternative to Assad and seek to build another false reality under the guise of stability. The regime seeks to create a reality where the Syrian revolution has lost, and Syrian popular resistance is exiled from history itself. The Syrian opposition at the same time does not exist and presents a grave danger, defeated and dangerous, reconciled and rebellious. Mere months after normalisation under the pretence of stability, Syria faces a wave of unrest stretching from the north to the east and south of the country: protests in Suwayda, clashes in Deir ez-Zor, the attack on the Homs Military College, and intense shelling in Idlib and Aleppo provinces by the regime forces.

Journalist and documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis explored this surreal senselessness of a world of “politics without politics” in his 2016 documentary “HyperNormalisation”. In an interview about the film, he explains how he was inspired by this concept, coined by a Russian historian Alexei Yurchak who was writing about what it was like to live in the last years of the Soviet Union: “In the 80s, everyone from the top to the bottom of Soviet society knew that it wasn’t working, knew that it was corrupt, knew that the bosses were looting the system, knew that the politicians had no alternative vision. And they knew that the bosses knew they knew that. Everyone knew it was fake, but because no one had any alternative vision for a different kind of society, they just accepted this sense of total fakeness as normal.” Curtis traced how, from the 1970s onwards, politics stopped saying that it could change the world for the better and became a wing of management, saying instead that it could stop bad things from happening. The normalisation with Israel and normalisation with Syria is precisely a manifestation of that management system – and it does not stop bad things from happening at all.

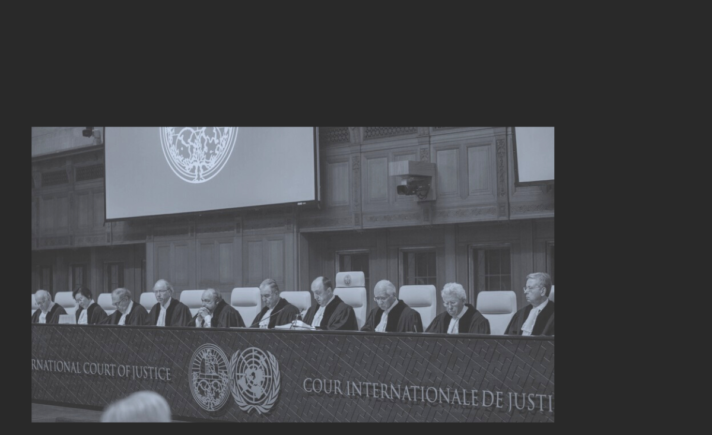

The regimes propped up by normalisation are both strong and fragile, similar to how, for Yurchak, the Soviet Union was simultaneously “eternal and stagnating, vigorous and ailing, bleak and full of promise.” Politicians don’t have an alternative vision to the brutality of the Israeli occupation or the Syrian regime. They are only trying to keep the world stable by managing the global system, without any regard for human life. In this sense, normalisation of mass murderers is a logical outcome of such a system. The absolute majority knows that the regional order, with its borders and its powers, is dysfunctional, corrupt and murderous and that the international system is failing. In recent years we have witnessed the normalisation of the failure to address the civil war in Sudan, Russia’s war against Ukraine, ethnic cleansing in Artsakh, Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, Ethiopian civil war, conflict in Myanmar, earthquakes, floods, and hurricanes, just to name a few. Western countries that claim to be guardians of universal values such as democracy and human rights watch on, complicit. Their position has eroded their credibility and created a vacuum which other actors have felt compelled to fill. Many of those who had hopes and expectations for the international community have resigned themselves to disillusionment and despair. Whatever institutions and rules this international order produced are irrelevant. Even the borders it produced throughout the 20th century are constantly contested by fighters and smugglers or paragliders and bulldozers.

A ceasefire without Palestinian right of return and an end to apartheid, settlements, and colonialism only prolongs the suffering of Palestinian people. It is urgent to imagine an alternative to the endless occupation in order to be able to resist the oppressive structures intertwined with it everywhere in the world. For Yurchak the spectacular collapse of the Soviet Union was both unexpected and imminent, and Soviet citizens both didn’t expect it at all and were prepared for it at the same time.

For years, Palestinian and Syrian friends and comrades have asked me if I truly believe that Palestine and Syria will be free, and I have always said yes. They will never be able to kill, torture and imprison every single one of you, and since your demands have not been answered, the struggle will continue. Perhaps it was always easier for me to imagine, at a distance from the brutality of these regimes, having grown up in Moscow, amidst the modernist ruins of something that was supposed to last forever.