1. Introduction

Driven by the realization that the political and funding ecosystems within which we operate are broken, a few of us, feminist collaborators started the Syrian Women’s Political Movement (SWPM). We envisioned a unique feminist partnership model with feminist donors.

The challenge was to set a new precedent. Current institutions often end up conforming with existing patriarchal norms and structures, designed to cater to able-bodied privileged men. This results in maintaining hierarchical dynamics, creating rigid timeframes, and sustaining unequal payment structures. Our thinking was to create a model that could surpass these hurdles.

However, such freedom comes at a cost while navigating a deeply entrenched patriarchal tide within society, culture, and people’s mindsets. Despite these challenges, our partnership model has thrived, positioning the SWPM as a strong and recognized women’s political movement in the Syrian context, and internationally, while also serving as a model for other women’s political collectives in the region. The persistent influence of patriarchal systems necessitates ongoing creativity and collective feminist approaches to subvert existing structures to find unique solutions for long-term success.

2. Traditional Institutions vs. Feminist Institutions

Institutions are generally designed to accommodate men’s needs and experiences, often neglecting women’s responsibilities and time commitments outside formal institutional settings. These biases stem from long-standing power imbalances and cultural expectations that assign caregiving and family management roles predominantly to women, without acknowledging their contributions. As a result, women often face significant challenges in balancing their responsibilities within the family and their professional settings.

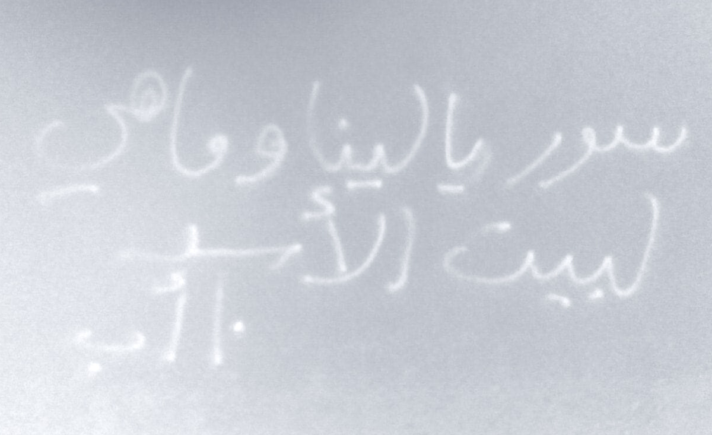

Traditional institutional structures have typically been designed around the ideal worker who can dedicate full-time hours, remain flexible, and prioritize work over personal commitments. This model tends to disregard or undervalue the unpaid labor and caregiving responsibilities shouldered by women outside of formal institutional structures. Consequently, when it comes to promotions and job opportunities, women may face disadvantages due to the perception that their caregiving responsibilities limit their availability, level of professionalism or commitment to work. And on top of this, the important work that women do in the private sphere, which is perceived by women as emotionally fulfilling and a source of pride is generally ignored if not altogether underestimated. The words, “housewife,” – ست بيت – or caretaker come with connotations of lesser status, and are sometimes used to devalue a person. Unfortunately, these important roles are often not recognized or valued within formal institutional settings when it comes to promotions and job opportunities. In fact, there is a deep level of denial of the rich nature of such expertise and experience. These caregiving roles generally require high skills in managing delicate situations and allocating resources, and conflict resolution skills not to mention pedagogical and education abilities. In such highly demanding contexts, women hone many of their capacities, including emotional intelligence, navigating conflicting demands, and management skills. And yet these abilities are not taken into consideration in the public sphere. And these particular skills, over the past few decades, have become in high demand in the workplace. However, the gender bias in institutional structures reflects systemic inequalities and societal expectations that have historically marginalized women and limited their access to power and decision-making roles.

This significance of rethinking these issues could have profound implications and practical consequences. Gender biases and stereotypes can lead to unconscious biases in hiring and promotion decisions, making companies and organizations miss out on unique skills and talents. In addition, these biases help perpetuate traditional gender roles and norms within institutions and hence reduce the potential for creative new contributions. As mentioned above, these biases contribute to a lack of public and cultural recognition and validation for the time and effort invested by women in caregiving and family management. Evaluation within these systems is often based on an industrial understanding of efficiency and quantifiable accomplishments, further reinforcing traditional gender roles and expectations, while also assuming full-time commitment.

Feminist institutions, despite their mission to challenge and dismantle patriarchal systems, can sometimes find themselves trapped within the same power dynamics and structures theyseek to overcome. This includes Syrian non-profit and civil society organizations as well as political initiatives and programs. In order to operate and secure resources, these institutions often have to navigate and conform to existing systems of power and resources, compromising their ability to introduce new creative angles, let alone challenge and transform them fully.

To address these systemic issues, a fundamental shift is needed in institutional cultures, policies, and practices. To create truly transformative feminist institutions, it is crucial to continuously question and challenge existing systems of power and resources. This involves advocating for new models that prioritize flexibility, and work-life balance, and questioning the structures and assumptions that perpetuate gender disparities. Implementing policies that promote flexible working arrangements, timeframes, and accommodating practices can help create a more equitable environment. Recognizing and valuing the diverse contributions and particular skills of women, including their caregiving roles, is essential for achieving gender equality and creating institutional structures that truly support women’s advancement.

By actively engaging in this new thinking, alternative political discourses could evolve where feminist institutions can work towards reshaping the cultural and institutional landscape to be more equitable, inviting, and reflective of the diverse experiences and contributions of all individuals.

It is worth mentioning, that there has been a growing recognition and questioning of these institutional norms, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the crisis has exposed the inherent flaws and inequalities within these systems at their peril. The pandemic has provided an opportunity for reevaluating traditional structures and norms, opening up new spaces for discussion and reform that challenge the patriarchal foundations of most of our work culture.

In response to the existing burdensome and inflexible institutional makeup, the SWPM was created as a pilot model for an institution that would challenge existing systems of power and resources to open doors formally closed to women, specifically within the political scene. The SWPM was born after the many and repeated attempts by Syrian feminists over the years to become part of the existing political institutions that operate within the already existing Syrian political bodies. Such attempts resulted in continuous failures. The political spaces were not welcoming to women who had been challenging the existing systems. The women had independent voices and demanded their full voting and decision-making rights. The founders of the SWPM then did the unthinkable. They created a political structure, an institution, that was led by feminists and ruled by feminist values. The movement’s aim was to challenge the status quo by working in parallel with the already existing political bodies. The SWPM based its vision and values on feminist ideals that are not echoed in the current universe of political paradigms. The movement did not base its legitimacy on the militarized patriarchal systems nor was it based on the credibility gained from international donors and stakeholders. On the contrary, its legitimacy rose through the connections and promotion of the voices and needs of the people on the ground: women, children, and all those marginalized.

3. Unique Feminist Partnership Model

The SWPM, the first women’s political platform in the MENA region, created a feminist partnership model with its feminist donors that has proven to be a powerful strategy to counter the patriarchal biases and constraints faced by feminist institutions. By choosing not to register itself and instead partnering with WILPF, the SWPM has found a way to operate outside the existing patriarchal political institutions that limit its reach and impact. WILPF, as a well-established institution, has provided its operative mechanisms to support the SWPM in functioning as a feminist organization, free from external interference or dictation. The SWPM, in turn, established its own internal structures, bylaws, and ways of work that are not bound by the chains imposed by traditional institutions, and ones that align with feminist principles. Through this partnership, WILPF provided the SWPM with supportive policies that allow it to function as a feminist institution. WILPF receives funding on behalf of the SWPM, granting the movement the freedom to pursue its political agenda while allowing it also to operate outside the constraints of patriarchal institutions.

This feminist partnership has not only enabled the SWPM to thrive but has also positioned it as one of the strongest and most recognized women’s political platforms in the Syrian political landscape. Its success has caught the attention of other emerging women’s collectives in the region, and elsewhere, who came to see it as a model to emulate. There have been several contacts, for the purposes of peer learning from such women groups including from Mali, Venezuela, and the Afghan Women Coordination Umbrella.

Nevertheless, the challenges posed by the dominant patriarchal values in the daily experiences lived by women across so many societies create a difficult environment for feminists to sustain their work. The persistent mindsets and ingrained cultural sensibilities hinder the intellectual and physical movement of women and block the advancement and effectiveness of the organizations they are part of. Overcoming these difficulties and roadblocks requires ongoing creativity and the ability to transform existing systems and ways of thinking and operating. Such reforms necessitate a collective feminist approach, where the power of the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The partnership between WILPF and the SWPM exemplifies this collective power, enabling them to challenge and subvert the oppressive systems that have long plagued institutions and hindered gender equality.

4. Feminist Support and Solidarity

The partnership between the SWPM and its feminist donors was not formed in isolation but was rather shaped and inspired by the support, solidarity, wisdom, and contributions of feminist leaders, and mentors who shared the belief in feminist values. Effective collaboration among feminists proved to be a crucial factor in the success of this feminist partnership. It is effective because feminists understand that their work is built upon the foundations laid by those who come before them.

The co-founders of the SWPM recognized that they were standing on the shoulders of feminist giants who had paved the way for progress and justice. This acknowledgment of the collective efforts and contributions of feminists throughout history strengthened the SWPM movement and reinforced its commitment to creating new avenues for women to make an impact. The collaboration among feminist members of the SWPM and their partners, especially on the ground in Syria, has been a testament to the power of shared knowledge, experiences, and collective work. It is through these collaborations that feminist institutions such as the SWPM learned how to gain the support of others, amplify their influence, and navigate the rugged terrains presented by patriarchal societies, cultures, and mindsets. By standing together and recognizing the interconnectedness of their work, the SWPM feminists have built upon the achievements of those gone before and are paving the way for the ones to come in the future.

5. Building Legitimacy and Credibility with Women on the Ground

The SWPM recognized the importance of collaboration and established partnerships with various organizations and individuals, both within Syria and in neighboring countries, as well as with women in the diaspora. These collaborations were based on principles of mutual respect, shared goals, and the freedom to lead on initiatives. This leadership position gave the SWPM the positionality and authority to collaborate with other organizations, and pool resources, expertise, and networks to implement projects and initiatives that support women’s advancement and evolve the SWPM’s feminist agenda. These partnerships allow the SWPM to leverage the strengths and capabilities of each organization involved in order to create a collective force with legitimate aspirations and credibility to work for positive transformative change.

Crucially, as an independent entity without official registration, the SWPM has had the flexibility to engage in partnerships on its own terms. This meant that it was able to maintain it political autonomy and ensure that its feminist principles and values are upheld in all collaborative efforts. As a result, the SWPM is not bound by the restrictions or bureaucratic processes that registered institutions may face, allowing it to forge partnerships that align with its vision and strategies without all the formality. The movement’s relentless efforts contributed in doubling the number of women involved in political processes reaching, for example, 30 percent representation in the Constitutional Committee.

Through these partnerships, the SWPM has tapped into the knowledge and experiences of women on the ground in Syria, as well as neighboring countries, and the diaspora. In turn, this way of operating ensured that its work was always informed by the realities, needs, and priorities of Syrian women in diverse contexts. As explained above, the SWPM valued the rich and diverse experiences and expertise of women who can bring a lot to the table, including and even more so to the political table. The SWPM invests in women’s social skills, networking abilities, and experiences in caretaking, making them serious stakeholders in any political process and negotiation. The SWPM recognized the high stakes women have in the well-being of those close to them and the larger community which positions them as fitting political negotiators. They stand to gain a lot in resolving any conflict. Hence, the emphasis by the SWPM to include women on the ground in the design of projects and decision-making processes has increased a sense of ownership among its members. This inclusion inspired the members to contribute actively and initiate projects, events, and programs.

The SWPM took a proactive role in creating news paths, political initiatives, and engagements at the international level and on the ground in Syria. By arranging public events during the Commission on the Status of Women at the United Nations, and at the Human Rights Council in Geneva and participating in briefings at the Security Council in NYC, the SWPM impacted the narrative on Syria by putting women at the forefront. In addition to press engagements and diplomatic visits, the SWPM created opportunities for Syrian women’s voices to be heard and hence created the contexts to reclaim their agency and presence, locally and globally. As a result, the success in expressing their political demands demonstrated that the SWPM’s commitment was not just to amplify their own voices but rather to ensure that their active participation was leveraging the demands of all Syrians invested in democracy and human rights.

Engagement with Syrian civil society was another crucial aspect of the SWPM’s work. They recognized the importance of including civil society perspectives and priorities. The women advocated strongly for engagement with civil society and highlighted key issues such as detainees and humanitarian concerns. By prioritizing the voices and priorities of the Syrian people, the SWPM aimed to enhance the credibility of the peace talks and worked to instill confidence in the political process.

Through these various strategies and initiatives, the SWPM played a pivotal role in advancing women’s political leadership and promoting gender equality within the Syrian political landscape. They were also instrumental in raising the profile of the Syrian cause at large. Their achievements serve as valuable lessons and inspiration for other women’s movements and political processes worldwide.

In summary, the SWPM’s model of collaboration and connections with organizations and individuals is built on mutual respect, courage to lead, and the advocacy of shared goals. By partnering with like-minded entities and engaging with women across different settings, the SWPM expanded its reach, strengthened its impact, and remained true to its feminist principles.