In Al-Wujuh al-Bayda’ [White Faces], Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury recounts the fictional murder of Khalil Ahmad Jaber, a telecom worker residing in Mazraa, West Beirut at the height of the Lebanese Civil War. Jaber was gruesomely tortured, his body beaten and burned. The murder is depicted from the point of view of an unnamed narrator, a political science graduate and travel agent residing in Beirut at the time. Bored of the monotony of war town Beirut, he develops an earnest interest in unsolved gruesome murders to keep himself occupied.

The narrator interviews five individuals with varying relations to victim. The story is then presented from the point of view of these witnesses: a civil engineer and neighbor of the victim, Jaber’s wife who witnessed his slow mental demise, the widow of the next-door building’s doorman who gave the victim some food once as he wandered around, a fida’i [fighter] and college dropout who very briefly came across the victim, and finally his daughter a victim of domestic abuse. Each of these witnesses provides a lucid and convoluted testimony surrounding their interactions with Jaber. Rarely do any of them stay on course, meandering into self-absorbed monologues. The accounts circle into a racket of porous information and hearsay. Jaber’s murder is never solved.

Khoury purposefully employs repetitions and run on sentences leading the reader into fruitless alleyways and dead ends. The violence and trauma depicted in Khoury’s novel is suffocating and dulls our ability to rationalize it. By stacking these contested narratives together, the novel acts as a dense sinkhole that sucks any avenue towards resolution or justice.

* * * * *

Today, if you open the Wikipedia page of the Lebanese Civil War, scroll down and look at the summary table you’ll find a packaged synopsis of winners, losers, results, casualties etc. In the “Belligerents” section, you notice four columns neatly stacking the various fighting sides. The quadrant below lists an array of the usual suspects leading them: Pierre Gemayel, Kamal Jumblatt, Hafez el Assad etc. Staring for a few minutes at this encyclopedic pastiche one might develop an assured sense of what happened during the fifteen-year conflict. The traditional narrative of a war fought between different religious communities holds sway. However, when inspected carefully, the summary box barely holds up under historical scrutiny.

The Lebanese Front quadrant, for example, omits us how Christian groups regularly fought amongst themselves over terrain and influence. Nor that the Lebanese Front itself came to an end when Bashir Gemayel, son of Christian leader and head of the Phalangist party Pierre Gemayel, decapitated all other Christian factions as he sought to “unite” them under his Lebanese Forces (LF) banner. The column also hides the numerous times Camille Chamoun, former president and head of another powerful Christian party, used to allow trucks full of ammunition to restock Amal fighters during episodes in which Amal, a Shiite group formed by the disappeared cleric Musa el-Sader, fought Palestinian fighters in the southern suburbs of Beirut.

The rest of the page itself is rife with misinformation. The Zahle Campaign section, for example, in which the Syrian army laid siege to the largely Christian town in the Beqaa valley and held minor skirmishes with Lebanese Forces concludes with a line that could only have been written by a Bachir Gemayel sycophant “This campaign paved the way for Bachir to reach the presidency in 1982”. The page about the Damour massacre, where Palestinian forces and leftwing secular Lebanese militias committed a massacre in the predominantly Christian town of Damour frames the massacre in sectarian terms by shifting the blame towards “Sunni militias” and while editors casually add the testimony of a witness claiming: “They were coming, thousands and thousands, shouting ‘Allahu Akbar! (God is great!)”.

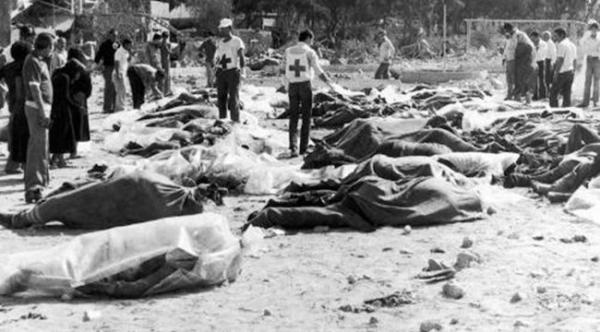

The page on the infamous Sabra and Shatila massacre is also a disaster. On September 16th, 1982, LF troops massacred almost 4,000 Palestinians in the besieged camps of Sabra and Shatilla in West Beirut with the aid of the Israeli Defense Forces. The IDF had invaded Lebanon, taken over Beirut, and exiled the PLO from the capital. The massacres received significant worldwide coverage and ultimately led to the dismissal of Ariel Sharon, defense minister and architect of the invasion at the time.

However, the dominant narrative on the massacres is that they were a form of retaliation. Two days prior, LF leader Bachir Gemayel was assassinated in an explosion. He was sworn in as Lebanese president less than a month before. Both Lebanese and Israeli accounts, blame bloodthirsty uncontrollable components of the LF seeking to avenge Gemayel and his aborted presidency. Yet historian Seth Azniska uncovered in newly declassified Israeli documents that Gemayel and Sharon discussed plans to permanently deal with the Palestinian camps in West Beirut long before Gemayel became president or Sharon’s troops laid siege to the capital.1 What happened in Sabra and Shatila was not a retaliation, it was premeditated.

This is the fundamental issue with Wikipedia as history. Anyone can simply write, edit, and alter the facts of any conflict to suit their own personal biases and uphold problematic discourses. In the thickness of these contested narratives, the facts disappear.

* * * * *

There are three things they teach you when you start a PhD in History: first, that you don’t really know anything and can’t simply know everything. Second, while historical processes are complex, that doesn’t make them inexplicable, on the contrary, but there are contingencies and multiple forces at play. Three, avoid the centripetal current of determinism, if you think something was inevitable what’s the point of studying its history?

Yet the Wiki page for the Lebanese Civil War fails at all three tenets. It’s designed and written to give its readers the pretense that they know everything and that long and complicated conflicts with several dynamics at play can be packaged into neat, serialized narratives, ready for consumption. The “Background” section of the Civil War starts with the sectarian fighting that occurred in Mount Lebanon during the mid-nineteenth century, when the region was under Ottoman rule. The rest of the section reeks of the inevitability of the conflict, absolving actors of their culpability. This is a recurring theme about the Civil War, that it was inevitable, that the country was doomed for conflict since its inception. Yet an entire country doesn’t simply slide into a Civil War. There are actors, agents, people who made decisions to cancel each other out and establish their dominance over others. There were structural reasons based on geographical and class cleavages that played important parts. Furthermore, the victims of the civil war, the dead, maimed, and disappeared, get minimal attention. Their suffering is but an afterthought in what was inevitably a geopolitical power play among global actors taking advantage of the fratricidal Lebanese.

Wikipedia elegantly packages local conflicts into segmented periods, factions and personalities that show a neat divide of winners and losers with clear timelines, maps, and bullet points. Easily created and consumed, those pages are nevertheless politically contested, given they can be written and edited by anyone, from any side. Though the democratization of news and information is welcome, what it has in effect led to is at best a collapse of critique and nuance, at worst, a platform for the manufacturing and distribution of misinformation.

The Syrian Revolution is another example where Wikipedia and social media platforms obfuscate the reality on the ground, rendering citizens invisible, and affording abusers and criminals the space to avoid justice and escape culpability. Firstly, if you Google search “The Syrian Revolution” the top answer is the Syrian Civil War. Once you click on it, the “Syrian Revolution” isn’t even there, what we have is also another protracted civil conflict, that renders civilians and victims invisible. Wikipedia editors could care less about how the regime brutally and violently suppressed a civilian uprising demanding democratic reform and justice.

However, Wikipedia is hardly the sole culprit in the internet’s misinformation problem. Twitter is main a cog in the misinformation machine. Twitter acts like a black hole that depletes facts and churns out the most deranged discourses.

* * * * *

The Syrian Revolution turned me into a Twitter addict. As an undergrad at the American University of Beirut I obsessively followed Syrian news on Twitter. I quickly honed down on a set of accounts to follow that kept both my excitement and rage fed. Along with Egyptian revolution, it was the first time a popular uprising played out in full, minute to minute, on a social media platform for all of us to watch. I had my own list of citizen journalists and reporters, from all major Syrian cities, tweeting daily about their lives. This was another facet that made the Syrian Revolution so accessible but also facile for consumption. The discourse wars however would soon render those voices invisible.

The Houla Massacre was the first time an online event sent me into a panicked frenzy. Pictures started creeping up late the night of May 25th, 2012.2 Bodies of children strewn around, stretched on concrete floors, plastered in blood. I remember feeling my stomach turn upside down. Para-militias attached to the Syrian regime attacked the defenseless town of Taldou in the evening killing 108 Syrians, among them 49 children. The Wikipedia page of the massacre provides equal space and merit to the government side which claims that it was actually Al-Qaeda who committed the atrocity. Never mind that Taldou was surrounded by regime forces and loyalist towns. The regime account on Wikipedia would have us believe that Al Qaeda terrorists, who were already present in Taldou, committed the massacre to show the regime in bad light. Another conspiracy against the impervious and noble Syrian regime. That night I learned that the Arabic words for melee weapon was silah al-abyad or white weapon.

Twitter became a battleground for supporters and opponents of the Syrian revolution. The opponents, a loose band of western leftist posters, avowed anti-imperialists, Hezbollah supporters, and Russian bots slowly but surely roamed the revolution’s events online, spamming bloggers, journalists, and Syrian citizens. Every regime crime or aggression was turned on its head and deemed a western PSYOP seeking to bring down a valiant anti-imperialist regime, unbending to American imperial pressure. The ease and ubiquity in which modern day disinformation is produced and distributed come as a consequence of the online wars over the Syrian Revolution.

The chemical attack on Ghouta and subsequent massacre was a particular inflection point. It both broke the online left but also cemented the regime’s ability to obfuscate and escape culpability of its actions as long as it had an effective hive of online supporters following suit. In the early morning of August 21st, 2013, the Syrian regime fired Sarin rockets at the Damascus suburbs of Ghouta killing over 1,500 Syrians. As soon as news broke out the war over the narrative of who was responsible was also let loose. There was enough open-source data on various social media platforms to demonstrate that the regime, solely, was responsible for this crime, as the venerable work of the likes of Bellingcat demonstrated. Not that many of us supporters of the Syrian Revolution had any doubt. Only the regime had chemical weapons, only the regime had demonstrated their willingness to mass murder thousands of Syrians so that the failed son of Hafez El-Assad can keep his throne. Regime supporters on Twitter and Facebook even dealt their hand early on celebrating the attack. Yet as soon as international actors became involved, the discourse quickly changed to deny, distract, and deflect from the regime’s culpability. The same script that was doled out in the wake of Houla was played after the Sarin attacks. Even Seymour Hersh, famed for uncovering US atrocities in Vietnam and Iraq, got in on the act, sullying his reputation to argue that it couldn’t have been the regime behind the attack, it must have been some Western-Islamist conspiracy. Hersh and other leftist western journalists, enraged over the lack of accountability for American atrocities in Iraq, would form a band of useful idiots covering up regime atrocities. The Wikipedia page of the Ghouta massacre relies on Hersh’s report to construct the regime’s side of the events. It sits there, neatly in a section below the factual events on the ground, providing some sort of false equivalency, a reassured sense that both sides of the story can be heard, that murderer and victim both deserve a right in telling what happened.

Not only did Twitter become a platform that amplified the worse conspiracies about Syria, but also as the war bloodily progressed, the myriad of citizen bloggers and journalists that ensured the voices of those protesting were heard – a feature that made it so attractive to start with – began to disappear from the platform. Journalist Austin Tice’s final tweet from 2012 is still up there informing us of his birthday plans with a local Free Syrian Army unit. HamaEcho, the pseudonym of a young Sami from Hama, and a great source of news from the beleaguered city in central Syria, who also disappeared, last posted “#offline forever. We are going to Ghouta soon. I have a bad feeling about this but the only thing that can happen is martyrdom or victory.”

Another extinct account was that of BigAlBrand, from Homs. I intimately followed Big Al. One night when the bombing on Homs was relentless, I naively sent him a private message offering our house in Lebanon in case he and his family needed some place to stay. I felt embarrassed a few moments later having not thought it through. How would I explain it to my parents if this stranger actually took me up on my offer? Big Al disappeared in 2013. He posted on his blog a year later that he was captured and tortured by regime forces. Big Al posted again a few times in 2016 and 2019. Last we know he was a refugee in Istanbul, alive but hopeless. I wonder how many Big Als never made it from regime prisons. Going over all these tweets today a sense of helplessness and dread takes over me. I shudder of what might have happened to Austin or Sami. Their tweets are still up there, strewn across old Twitter, like a charnel house filled with my youthful aspirations.

* * * * *

In Fall 2014, I moved to London to pursue a graduate degree. The moment I landed I eagerly sought a political group at my university I could join so we could hold events about the Arab Spring. I joined the local pro-Palestinian advocacy chapter. At one of the first meetings, an abrasive Latinx student, who presented himself as a fervent ally of all oppressed peoples came up to me and introduced himself. He asked me where I’m from, I said Lebanon, the conversation quickly turned to the events of the Civil War, he was eager to share with me how Christian militias were hellbent on destroying the Palestinian revolution. Though I nodded, eager to demonstrate my leftist credentials, I timidly countered that frankly the Lebanese left and even some Palestinian factions equally engaged in blatant sectarian killings.

On February 4th, last year, the body of Lokman Slim was found in his car near Sidon in Southern Lebanon. Slim was a Shiite Lebanese archivist, historian, and activist. I did not know Lokman, but I was vaguely familiar with his work at Umam, an organization he founded dedicated to documenting and preserving the memories of the Lebanese Civil War. Through Umam, Slim even interviewed and collected testimonies of LFII fighters who participated in the massacre of Sabra and Shatila. He was a man zealously committed to the notion that for any form of transitional justice to occur in Lebanon a record and documentation of events must be kept. The road to justice, to moving on, lay in our ability to archive and acknowledge.

Slim was shot four times, he was recently organizing and meeting with other Shiite dissidents. A few hours after his death, a clear and succinct discourse was being shared online by those who opposed his work from reactionary anti-imperial leftists to Hezbollah supporters. The discourse sat on two pillars: first, he had been living in an area under Hezbollah control for so long, why would they kill him now? Second, it was in fact Israel who killed him to sow discord and mischief in the country. It was the same old script we have seen Hezbollah apologists peddle whenever the group did something outlandish like invade Syrian towns or kill other dissidents in Lebanon. These apologists will deny, obfuscate, and muddy the waters along a well-structured discourse just enough to deflect responsibility. Any truth of the circumstances will take longer to come out precisely because of the overabundance of information available online, and the availability of tools for anyone to manipulate the facts.

The Middle East today is sinking in deaths and forced disappearances where accountability and justice are nonexistent. Online platforms help perpetuate this miscarriage of justice. Wikipedia and Twitter are mercilessly patrolled by a zealous bots and willful idiots ready to deflect and deny the culpability of our rulers in our oppression. At his eulogy at his home in Haret Hreik, standing, minuscule, over a smiling portrait of her son, Lokman’s mother charged those attending to continue her son’s work. If we are to carry on Lokman’s legacy and honor the memory of the thousands of victims of the Arab regimes of oppression, the least we should do is to properly document, archive, and retell their stories in the hope that one day we may hold their killers accountable.