Six months to the day since the enormous blast that ripped through Beirut’s port last summer, Lebanon awoke Thursday morning to news of yet more horror and criminality.

Lokman Slim, a pillar of Lebanese civil society, known for his work memorializing the 1975-90 civil war, as well as his vocal criticisms of Hezbollah and its allies, foreign and domestic, was found shot dead in his car in south Lebanon, after visiting friends in the town of Niha on Wednesday. He was 58 years old.

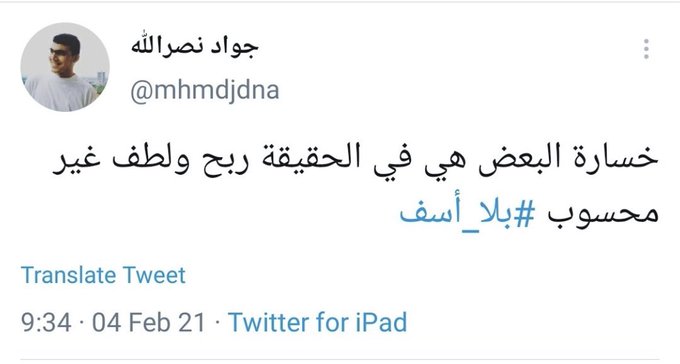

As the gruesome news spread on Lebanese social media, fingers were quickly pointed at Hezbollah, the de facto authority on the ground in the area where he was killed, whose official media outlets have explicitly denounced Slim for years. A Twitter account believed to belong to the son of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah appeared to celebrate the news of the assassination, saying, “The loss of some is in fact a gain and unexpected mercy #No_Sorrow.” The tweet was later deleted.

Without doubt, Slim’s criticism of Hezbollah—and the Iranian and Syrian regimes, and Lebanon’s own corrupt ruling class, and tyrannical authoritarianism of all stripes—was an important part of his activism, from which he did not shy. On any given day of the week, he could be found on any number of Arabic TV stations voicing his perspective as one of Lebanon’s relatively few Shiites prepared to speak out publicly against the powerful Shiite Islamist Party of God. For Western journalists in Beirut, such as this author, he was always willing to offer his time to comment on the issue of the day; forcing us to marvel on each occasion at the fearlessness with which he spoke his mind, despite the constant campaigns of harassment and threats he faced.

Yet Slim was always far more than a mere media pugilist and TV talking head. Through the UMAM Documentation and Research NGO that he founded and ran, he worked meticulously to build up an archive dedicated to the memory of Lebanon’s 1975-90 civil war. Among the invaluable artifacts he collected and exhibited to the public, free of charge, was the bus that was shot up by militiamen on 13 April, 1975, in the massacre that is generally taken by historians to mark the war’s starting point. If the day ever comes that Lebanon creates an official museum consecrated to the war, it will owe a considerable debt to Slim’s efforts.

And he did much more besides. Another of his NGOs, Hayya Bina (“Let’s Go”), taught English to women in rural communities and sponsored dialogue between clergy of different faiths, among other activities. Syrian friends and colleagues, too, have met the news of his murder with grief, recalling his outspoken support for the Syrian revolution, and his work highlighting the suffering of prisoners in the Assad regime’s dungeons; particularly in the award-winning film he co-directed with his wife, Monika Borgmann, about Syria’s notorious Tadmor prison. Slim knew as well as anyone how inseparably interlinked are the Lebanese and Syrian systems of violent oppression, and how one cannot hope to resist the one without also combating the other.

His personal life was lived with extraordinary courage. In July 2006, when war broke out between Lebanon and Israel, Slim happened to be in the United States. While everyone in Lebanon with the means to do so was scrambling to flee the country, Slim made a point of flying into it, aboard a French military helicopter from Cyprus, to return to his house in the heart of Beirut’s southern suburbs, which had by then lost all its doors and windows as a result of Israel’s punishing bombardment.

Slim remained in this house for the rest of his life, despite the years of organized and systematic defamation, harassment, and threats he would continue to face; in official Hezbollah media such as al-Manar, as well as unofficial mouthpieces like al-Akhbar newspaper. I know I wasn’t the only visitor to his street—smothered with Hezbollah’s yellow-and-green flags, and posters of the young men killed fighting in Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere—to have been perplexed at Slim’s choice of residence. Yet he appeared to see it the other way around: why should he have to move because of them? While avowedly secular, and nobody’s idea of a religious conservative, I got the impression he felt an unspoken, instinctive attachment to the older Shiite traditions that predated the Iranian Revolution and its novel ideology of conquest and aggression; an identification with the traditions of tolerance and moderation that had generally been the way of south Lebanon’s Shiites for centuries before Khomeini’s alien fanaticism arrived in 1979.

In our last meeting, several years ago in his office, he said a sentence which for some reason has often recurred to me. Engulfed in his cigarette smoke, with his trademark wide grin on his distinctly reddish face, he laughed in his deep, raspy voice that Hezbollah’s outlandish claims against him—that he was a “traitor” and “Zionist agent,” and so on—had gone from being an accusation (tihme) into a mere joke (nikte); something nobody seriously believed or really cared about anymore, even among the Party’s base. It’s a revealing remark, in retrospect; suggesting he never truly imagined Hezbollah would bother to do him physical harm. He’d got away with it all for long enough, after all.

Today, we learn anew that the accusation is no joke whatsoever. The clouds above Beirut’s still-obliterated port have grown yet darker, and no free-thinking mind in Lebanon will sleep easily tonight. In the memory of Lokman’s fearless grin, however, they may find courage—and in the silhouettes of his cowardly murderers they may know their enemy.