This text is inspired by the testimonies of many Syrians imprisoned by the Israeli occupation. Some are my own experiences, while others I only heard or read about, but carried with me long afterwards. Pronouns may change throughout the stories, as at times I combined several testimonies in a single speaker. While this may risk adding some confusion to the text, most of us do not recall everything that happened with perfect clarity; perhaps as a way of coping with the brutality of these experiences. We forget minute details. Denial and the suppression of memory are eminently human traits. When writing about events imperfectly remembered, we do our best to fill in the gaps. From a glimpse here and a feeling there, we rebuild and restore the complete narrative. All history is narrative, and narratives differ in how such gaps are filled. I may omit certain details here and there, out of forgetfulness or oversight, or out of the prudent dissimulation that still enshackles me, and all those in this text. Hopefully, the day will come when such shackles are released forever.

At the outset, I had sought to document the memory of the resistance movement waged by Syrian inmates in the Israeli occupation’s prisons. This long-forgotten history is rich in meaning, significance, and symbolic value. Yet I wouldn’t wish to reduce these experiences to mere symbolism. 54 years on from its inception, this narrative is an integral part of a larger story; one of Syrian men and women, many of whom lost their lives as a result of imprisonment. Others lost their hearing, or lost years and decades through life sentences. Some lost their families while stuck in a cell, and others lost the ability to sleep without nightmares. Since they are human beings, moved by the greater Syrian loss—that of freedom—I will attempt to honor their sacrifices in order to defy that loss. This will not be through documentation in the legal sense, but rather documentation which allows the reader, if only for a few moments, to see through the eyes of those who were there.

I dedicate this text to those men and women—those who were martyred; those who were freed; and those yet to come.

Arrest

I can remember the time exactly—3:02—because I looked at my phone as soon as I heard those sudden, heavy pounds at my door. I was alone, and my heart was beating fast. A few seconds later, from the sounds of heavy army boots that I heard running up and down the stairs, I realized with terror that soldiers had come.

They pounded at the door. When I didn’t answer, they tried to break it down. I don’t know why, but I tried to hide somewhere in the room. As soon as the soldiers got through the door, I realised hiding would scare me more than confrontation. I came out, and after a short interaction in which I cursed at them in fluent Hebrew, they took me away. I couldn’t resist much. Other comrades did in fact attempt to resist the soldiers during their arrests. At least one of them had to be drugged by the soldiers to pacify him as they arrested him. I saw it: they forced a cloth soaked in liquid onto his nose, and as he inhaled he lost consciousness completely. It was more of an abduction than an arrest.

They searched my room, finding nothing apart from some books, a Palestinian flag, a Syrian revolution flag, and a poem by Muin Bseiso hanging on my wall. I felt no fear as they forced me into the military jeep; instead I felt a sudden sangfroid, and a sense of calm mixed with unexpected derision. I didn’t care about their insults, or the plastic ties binding my hands so tightly they began to bleed.

After my arrest, I was beaten badly. My head hit against a wall, and I started bleeding from deep within my ear. No first aid was provided, nor was I allowed to go to the bathroom to clean myself up. I was left like this for days, until blood coagulated deep inside my ear, blocking it. Later, when I was finally allowed to clean it properly, the dried blood was excruciatingly painful to remove, as though part of my brain was coming out with each lump. Whenever I’m asked about my arrest, one fact always sticks out to me: I lost seventy percent of the hearing in my left ear.

Equations of fear

My friend, who I’ll call “N;” the daughter of a freed prisoner; is the one who worries me most, as she is deeply affected by each arrest. She has seen arrests from an early age. Her childhood was shaped by prison releases, prison visits, and incursions by the occupation’s military coming after her relatives. This childhood raised in her a deep love for Syria, and for the act of resistance, as well as an ongoing, uncontrollable fear of imprisonment. Hers is a time-honored equation of fear.

The suffering caused by imprisonment is never limited to the prisoner themselves; it extends to their families, who also experience the meaning of loss. What affects N even more, each time there is an arrest and/or imprisonment, is that the families of Syrian prisoners have to face the captivity, absence, and loss on their own, given the fear among the rest of the occupied community, as well as the wilful neglect of the Syrian state. Everyone imprisoned was taken precisely for breaking this equation of fear. Since my arrest, my little sister has been afraid of “Hebrew” soldiers, as she calls them, more than any other child in the Golan. As for me, nothing scares me anymore except the fear in her eyes. This is a new equation of fear.

Interrogation

At first, I was placed in a room right next to the interrogation rooms. I was interrogated for fourteen hours straight on the first day; fifteen on the next day; and I don’t even know how many on the third and fourth days. Some people have had to endure this for months on end. I was tortured using the so-called shabeh (“ghost”) method, with a putrid bag placed on my head for many hours. The interrogation also included sleep deprivation, beatings, suffocation, denial of toilet use, deprivation of food and family visits, and deprivation of medicine and sanitary products. This is all in addition to psychological torture, which was often more difficult than the physical aspects. These are but a few summarized examples for those who imagine the occupation’s prisons are humane or devoid of torture.

For those who want details, I’ll say this: the on-duty policeman who received me dragged me into a narrow yard, where I could see my childhood friend hanging there in a shabeh; his hands hanging upward; the filthy bag covering his face. I didn’t dare call out to him by name, but I felt safe. It was certain that he hadn’t confessed to anything.This passage is dedicated to the sacrifices of the liberated comrade Ayman Abu Jabal, and is inspired by his prison memoirs.

They placed my head inside that bag, handcuffed me, and raised my hands up in the same position I’d seen my friend in. I didn’t say a word as they left me there in the sun. He said nothing, and neither did I. I was there for several hours, looking at him. I wanted him to get a little closer, to feel him next to me, but I held my emotions. Numbness had begun to creep into my elevated hands, and after hours of being in the shabeh position under the sun, they put me back in my cell. It was night time. I tried to enjoy the view of the stars in the night sky for a few seconds, before the dungeon engulfed me once more.

The next day, as I was taking out the toilet bucket from my cell, I saw some of my comrades. I had trained myself to get used to the sounds of screaming, moaning, and beating coming from their cells. But suddenly, after this brief encounter, I could no longer stand the noises. For several days, nothing changed: no one paid me any attention; the officer would bring me food without a word. Suddenly, I began to lose my temper: What has come over them? Why aren’t they coming? Have they forgotten I’m here? I started to miss the sounds of pain that had brought me such deep dread and terror. Now, it was as if I were in a place deserted by its residents.

I had obsessive, frenzied thoughts: Why don’t they take me to the interrogation room? Let them do to me as they wish; beat me, hang me up by my hands, bring that bag of filth and leave me under the scorching sun! Do anything, just don’t leave me here consumed by loneliness! I became afraid of the sleep for which I had longed. I would think, then think again. Perhaps my comrades had betrayed me? I can no longer hear them screaming. They must have confessed! I’ll betray them too. I’ll admit to everything.

Silence

When I saw my comrade after long days of solitary confinement, he asked me, “Will this hell ever end?” I said, “I don’t know.”

A heavy silence reigned. It haunted me, just as it does now as I write these words. Despite the brutality, I said nothing. This extraordinary ability to be silent was the reason I survived. In the silence, I went to other places in my mind. My mind was dissociating, transporting me to another world entirely.

In captivity, non-confession is a moral virtue that a person learns long before they embark on resistance. It is a value that many could not live up to, due to the brutality of the interrogations and the methods of torture used against them. Those who break are not to be blamed, for silence is twice as painful as speaking.

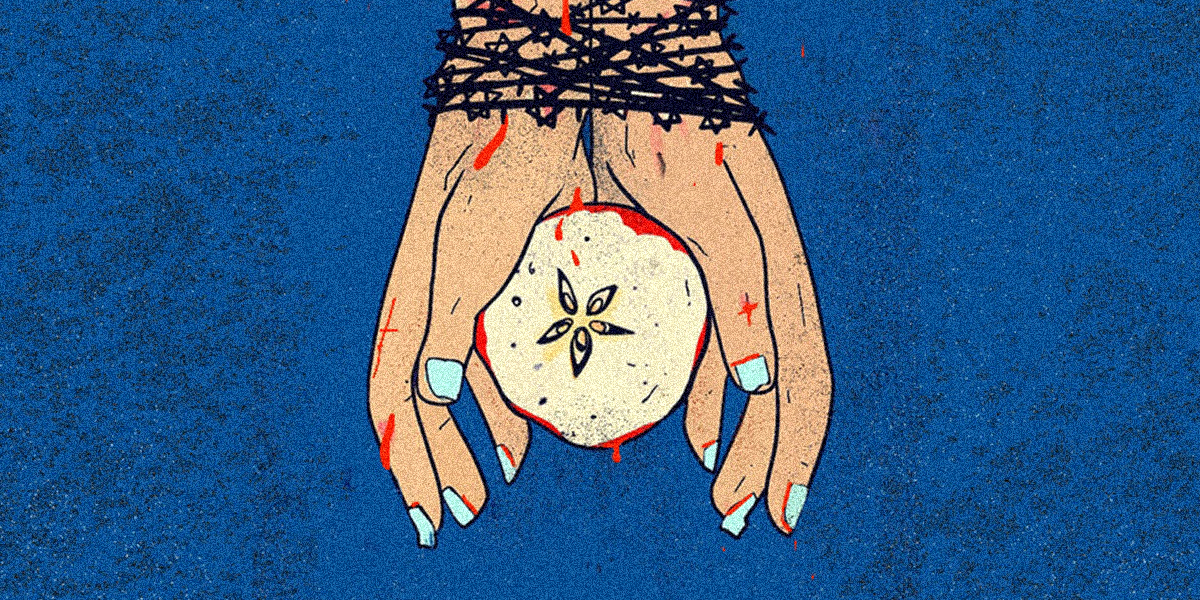

I slept poorly in the interrogation cells. When I left them, my limbs were covered in blue bruises from the biting cold. I smelled so bad I nearly fainted myself, and my clothes were worn through. I had had no change of clothes for the entire time of my imprisonment. I also couldn’t really eat. My movement was restricted by the tremendous pain deep inside me from the lack of food. It hurt to urinate, because of the severe beating of my hungry, aching organs. I used to eat the fruit that sometimes came with the meals; an apple or piece of plum. Whenever I ate an apple, I would smile, thinking of the Golan proverb about how there were five seeds in an apple, not six, forming a pentagram star like on our flag, not the hexagram of theirs.

Silence becomes your companion during interrogation and imprisonment, and indeed afterwards. This “cost” me years of companionship and closeness to Syrian prisoners, especially the veterans, who are almost never heard speaking about themselves. They may discuss the ongoing situation; prison-related events; deals made; but never share information about their resistance work, even today, after decades of activity, captivity, and release from prison. It’s almost impossible for them to share their feelings, weaknesses, or details about the torture they endured. Their refusal to divulge information comes on the one hand from their discipline and commitment, as well as a continuing deep belief in the cause. Yet their silence is also a personal one, through which they seek to avoid the rush of pain their repressed memories might evoke.To the comrade Yusuf Abu Shakib, who taught me the importance of love when it comes to the cause; and who shed a tear in front of me which I will never forget. As for the younger prisoners, they speak a little, but only rarely. In all cases, silence is our companion. But sometimes, the silence itself is fatal, like a slow death.

In court

In another time, before the age of pragmatism and individualism in which we now live; when principles still mattered; a large number of prisoners from the occupied Golan were tried in absentia due to their refusal to stand before an Israeli judge. To rise out of respect for the judge at the beginning of a court session may seem a simple and blameless act. To the prisoners, however, it meant recognition of the legitimacy of Israeli courts. They were shackled, exhausted, and battered after their tortuous journeys, and, instead of standing before the judge, they sang the Syrian national anthem in court. For this reason, they were tried in absentia, and years were added to their already incredibly long sentences. The most severe penalties were handed down. They were made to pay for upholding not only the Syrian identity of their land, but also the moral symbolism of Syria.

As for myself, I stood.

Orphans united

One comrade, trying to convince a group of young and enthusiastic men who had not yet suffered imprisonment, says, “How alone we were!” A veteran adds, “He’s right.”

In 2004, we Syrian Golan inmates were in prison. Most of us were serving long sentences, and our conversations at the time centered around the prisoner exchange deal between Hezbollah and Israel. We all crowded round the radio to hear the names of the hundreds of prisoners included in the deal. It was a painful scene, with comrades celebrating the news of their liberation, next to others whose names went unmentioned. One name after another, starting with those with the longest sentences, until the list was finished. Hezbollah’s leader, “His Eminence” Hassan Nasrallah, mentioned not one Syrian prisoner from the occupied Golan. A heavy moment of silence passed, broken by Nasrallah’s voice, as he said something to the effect of, “As for prisoners from the occupied Syrian Golan, we did not include them in the deal, because they accepted Israeli nationality. Therefore, we say, ‘May Israel do as it pleases with its citizens!’”

For the unfamiliar, the story of the occupied Syrian Golan can be summarized very simply as follows: occupation and military rule; popular uprising; siege; hunger; oppression; and martyrdom; all for the sake of our continued rejection of Israeli citizenship. This is the essence of our entire struggle in the Golan. Did Nasrallah, the so-called “Leader of the Resistance,” really not know this?

The cliché resurfaces: “How alone we were!” I think to myself now: how alone were we, really? As alone as all other Syrians? We shared more with other Syrians than I’d imagined at first. Even if we had little in common, what we had was crucial, and more than any of us had thought. To this day, our common lot is a loss of freedom, and a sense of unity; the unity of orphans; orphans of the body politic.

After the deal, Palestinian prisoners would often tell us, “We don’t even have a state, and yet military factions negotiate for us and try to get us released. You have a state holding remains of Israeli soldiers! You ought to be stronger than us, and enjoy real support, not the other way around.” Usually, after such exchanges, silence prevails, at least for me. Do you remember the silence I talked about? This is our third common denominator.

In the enemy’s cells, during family visits, I hear about the Assad regime’s massacres of civilian revolutionaries. I decided to go on hunger strike, hoping my solidarity might break the concrete walls of Gilboa prison; break the ceasefire line and its barbed wires, and reach Daraa, if not further. In my absence, in the cell to which I was abducted, the Assad regime erased me, too. Upon my release, only a few came. My name has been wiped from all Syrian media and government records. An interview with my sister on Syrian TV was cut short when she mentioned me. Later, I saw my name on the lists published by Zaman al-Wasl of those wanted by the Syrian regime’s security branches. Here I am, in the enemy’s dungeons, paying with years of my life: absent from the Golan itself, while the Golan is absent from Syria. All the while Syria; far from both me and the Golan; is trying to render me absent as well.

I went on hunger strike for three days. Some of the prisoners expressed solidarity with me. Few understand the strong link that exists between the two causes. People have forgotten that a bridge exists between Palestine and Syria, built by the bodies of the Golan’s martyrs and prisoners. The prison administration punished me harshly to stop me resuming my strike. I was not allowed visits for a month, and was made to pay a fine. I was also transferred to solitary confinement for 72 hours, and prevented from receiving or sending any messages.To our compass, the freed captive Wiam Amasha.

“How alone we were,” and still are. If we oppose the Assad regime, we’re ignored in the prisoner swap deals, and in public opinion generally. If we support the regime, we’re exploited in the propaganda of the so-called Axis of Resistance. In both cases, we’re used in order to compare the occupation’s prisons with those of the regime, and told by those who like such comparisons to “Thank God that we’re Syrians blessed to be under occupation.” Alone we resist; alone we are forgotten; and alone we resist being forgotten.

No one sees us as people, due to ideology and interests.

The book

I asked the jailer for a book. He said, “We only have one book,” and brought me a Qur’an. I asked my family for a book, and they brought me Yassin al-Haj Saleh’s memoir of his time in Hafez al-Assad’s prisons. I asked the jailer for my book, but he refused, saying “terrorist” books were forbidden. I told my family to take the cover off and replace it with a cover of a religious book. They put a cover of a Qur’an on, and I was able to read al-Haj Saleh in prison after all.

During an earlier prison stint, I had asked the jailer for a book, and received the same reply: “We only have one book. Do you want the Qur’an?” I said yes, and began to recite the chapters (suras) in order: al-Fatiha, al-Baqara… and that was it. Al-Baqarah is so long! I grew angry, and didn’t finish it. I ignored the chapter order, and went looking for nice verses here and there throughout the Holy Book. Thus I can say that reading just two suras was enough to get me released.

On a third occasion, I smuggled out my first poetry collection using what were known as “capsules.” And in another poetry book, I smuggled out a poem dedicated to the Syrians in Assad’s prisons:

Here, as well as there, the policeman would be

As fragile as dry grass, did he not

Lean on a rifle

Guarding his dunes of fear

Against the pulse of revelation

In a song.

If some insults are exchanged,

The intent remains clear:

Nothing but conforming to false masks.

These two are twins

Of one umbilical cord.

Their shadow on the ground

Is one massacre completing another.To my dear friend above all else, the liberated comrade Yasser Khanjar. The poem, titled “Between Two Cells,” is his, written from his Israeli prison cell to Syrians jailed by the Assad regime.

More recently, I managed to smuggle out a political article, which was published. As a result, I was tossed into solitary confinement for many long days in the Negev desert prison.To the freed prisoner Sidqi al-Maqt, despite everything.

*

It’s difficult to write this piece without stopping. It may even be a mistake to do so. My heart beats fast as I immerse myself in the writing. I see what seems like a reel of memories: blurry images in black and white, and sometimes sepia, like footage of the story. To dive into the depths of denial and forgotten memories, trying to extract a truth written in literary style, is a terrifying prospect. The depths of memories, and what they mean, almost suffocate me. The seas of this history of pain are expansive, and I will never do them justice. Ultimately, this text tells only part of the story, which is part of my own story; of all of our stories. It is an attempt to integrate the personal into the collective, because I cannot achieve both separately: I cannot write about myself as distinct from them. I fear I would do neither side justice. And to see justice done is the goal, over here as over there.

[Editor’s note: This article was originally published in Arabic on 23 July 2020.]