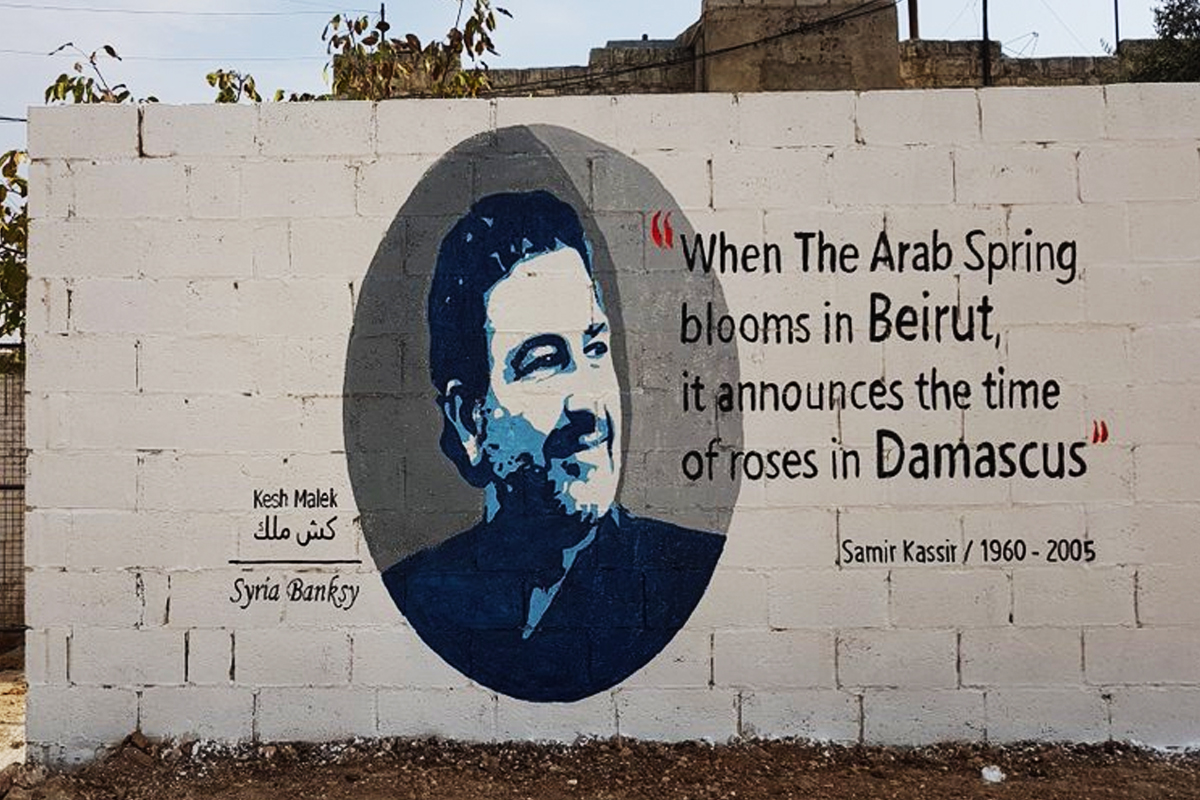

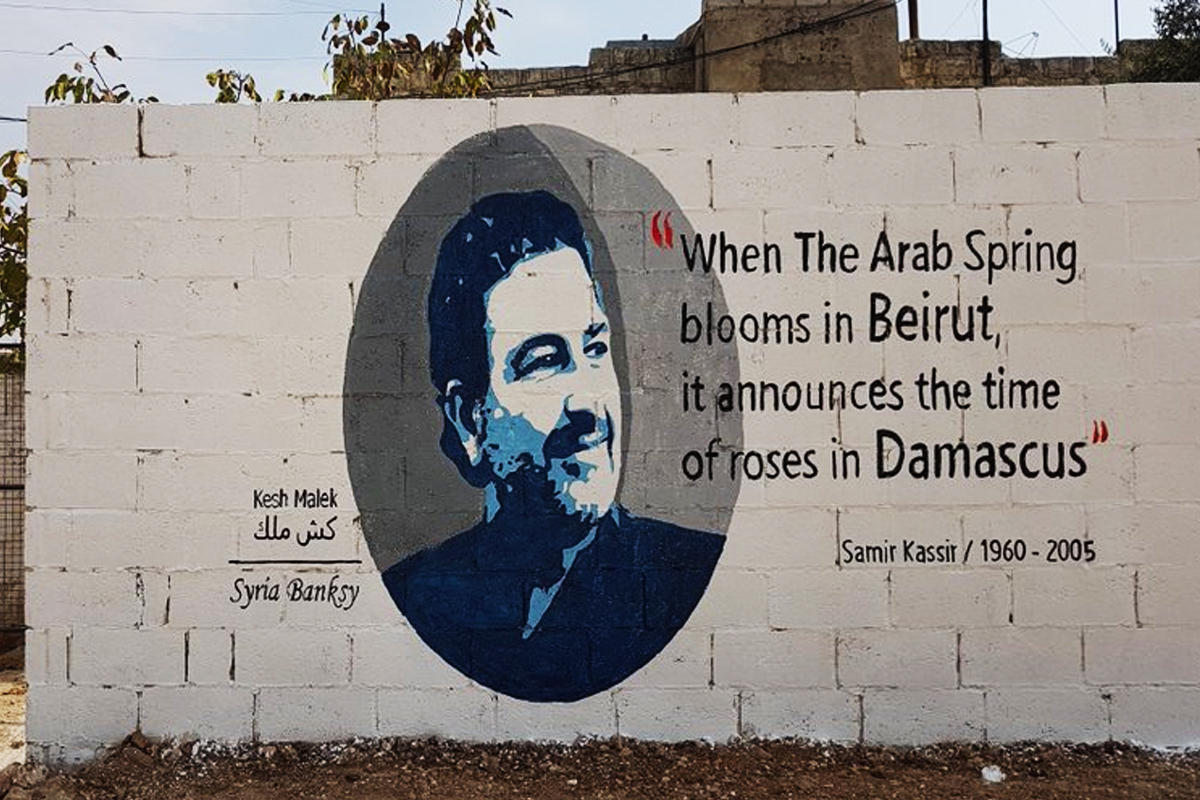

On 22 October, five days into the ongoing Lebanese uprising, an artist based in Syria’s Idlib drew a mural of the late Palestinian-Syrian-Lebanese intellectual Samir Kassir with the quote: “When the Arab Spring blooms in Beirut, it announces the time of roses in Damascus.” Kassir wrote these words on 4 March, 2005, less than three months before his assassination, in the context of Lebanon’s Cedar Revolution against the Syrian regime. Six years later, in March 2011, the time of roses came to Damascus.

Today, Lebanon is undergoing another moment of awakening, but one which comes eight years after that same regime turned its weapons, once again, against the Syrian people. Since then, over a million Syrian refugees have fled to Lebanon and, in recent years, worsening economic conditions have provided Lebanese politicians with more material with which to scapegoat Syrians.

At the same time, Syrians (and Palestinians) are participating in Lebanon’s ongoing protests, but most, including the co-author of this piece, choose to do so from the sidelines out of fear of being targeted by security forces and/or sectarian media outlets.

The emotions felt now by a majority of Syrians in Lebanon are thus as diverse as the protesters themselves. They range from sweet nostalgia to profound melancholy; from pure euphoria for another people’s uprising in the Middle East, to feelings of sheer panic at the thought of potential backlashes against Lebanon’s refugee community.

With the revolution now well into its second month, it may be time to reflect and consider some of the pressing flaws of this beautiful uprising in the spirit of one of the words most hyped-up in recent years among young activists from various backgrounds: intersectionality.

As the political establishment uses its usual tactics of sectarian fear-mongering, fake news, and disinformation to counter the popular movement, Syrians in Lebanon have additional concerns and fears that should be addressed at a wider popular level.

A diversity of reactions

The revolution has so far been exemplary in its creative approaches, from the reclaiming of privatized public spaces to hosting public discussions, lectures, and even brunches; to roadblocks and hilarious banners.

One manifestation of this creativity has been chants heard on a daily basis throughout the country. These often borrow from pre-existing tunes or words adapted to suit the local context. Most notably for our purposes, they have included adaptations of famous Syrian chants such as “Yalla erhal, ya Bashar” (“Come on, leave, Bashar [al-Assad]”) and “Hurr hurr hurriyeh” (“Free free freedom”).

The “Yalla erhal” song has been especially popular, with renditions varying from replacing Assad’s name with that of various politicians, especially the president, to “Come on, rise, Beirut” and “Come on, go down to the streets.”

These adaptations of Syrian chants are one reason some Syrians are reacting positively. As one Syrian told the authors, “We are a part of this society, so even if we’re not the ones giving speeches, we should be physically present in order to bolster the power of the masses and support them in raising their voices against those in power.”

At the same time, others are genuinely worried. Another Syrian said, “This revolution isn’t ours, and there’s no point being on the ground since it will be used against us to call us instigators.”

Yet, whatever their impressions, one dominant feeling expressed by every Syrian activist involved in the debates surrounding the Lebanese revolution is that of nostalgia mixed with undeniable envy.

Many Syrians, particularly those in their mid-to-late-20s, were taken back to their memories and hopes from the early days of the Syrian revolution, when the first protests included peaceful resistance, symbolic acts, and a non-sectarian community feeling. They were roughly the same age as many Lebanese protesters are now when they took to the streets of Daraa, Homs, Aleppo, Latakia, Damascus, Daraya, and so on.

This walk down memory lane is quickly accompanied by a feeling of envy, itself often combined with shame. The Syrian revolution wasn’t able to remain this peaceful for long. In Lebanon, the relative safety of protests has allowed for room to grow.

Syrians, by contrast, had to quickly adapt from mass protests to escalations of regime violence, mass disappearances, and the widespread use of torture tactics against any individual unable to run or hide.

Fear of the army and the flag

The continuous outpouring of support and respect for the Lebanese army has also made some Syrians feel uncomfortable. To Syrians, the military’s presence is associated with its connection to the regime and their experiences of violence and oppression.

As for the Lebanese, many have expressed gratitude for the army’s presence and behavior so far, seeing it as a protector against Israel and a preferred alternative to Hezbollah. The fragile nature of the Lebanese state and the volatility of the country’s economic situation seem to have limited, for now, the Lebanese military’s willingness and perhaps even ability to inflict violence.

But they still do represent a part of those in power, and have at times inflicted violence on Syrian refugees.

The same goes for the usage of the Lebanese flag and, less frequently, the army flag. It’s being used by protesters as a symbol of unity against sectarianism, and is seen by many as a much-needed alternative to the plethora of sectarian party flags that so dominate Lebanon’s landscape.

To Syrians, however, the omnipresence of Lebanese flags is also a reminder of their foreign status, of being merely temporarily tolerated. As much as the Lebanese excitement for their movement is justified, it does raise fear of a populist and nationalist movement and government that might not only cease tolerating the Syrian population in Lebanon, but possibly prepare an active campaign of deportation.

Thus, one realistic way for protesters to address this concern is to demand that the army be held accountable by civilian courts, which it currently is not.

The fear of being scapegoated

These concerns are worsened by the fact that the current president, Michel Aoun—himself a former army general—and his son-in-law, Gebran Bassil, the current caretaker foreign minister, have been particularly obsessed with Syrian refugees. In a recent speech marking his third anniversary in office, Aoun even listed an increase in refugee returns (explicit deportations were not mentioned) as among his finest “achievements” within the first 30 seconds.

Aoun’s TV station, OTV, and political party, the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), have indeed developed a reputation for scapegoating Syrians. One pundit on OTV even made it very explicit, saying, “Just as we went to Syria and buried their revolution, we will bury this revolution in Lebanon.”

True to form, OTV has repeatedly focused on the Syrian presence—real or imaginary—among Lebanon’s protesters. It has been part of the narrative of the ruling establishment, and particularly the FPM, Amal, and Hezbollah, that the protesters are all funded by foreign powers; a conspiracy theory familiar to any Syrian.

With this in mind, it is unsurprising that Syrians express hesitation and genuine fear of being seen in the revolution. Even those who remain hopeful and positive towards it find themselves in an uncomfortable position, often wondering whether they would be welcomed as participants or not.

Hope for a better future

Samir Kassir linked Lebanon and Syria in ways that have been forgotten by many Lebanese, including those who rose up against the regime’s occupation. Whether or not this bond is strengthened again will depend on whether Syrian refugees, and possibly even the older community of Palestinians, are scapegoated, which in turn will depend on whether protesters themselves resist, alongside Syrians and Palestinians, against these tendencies.