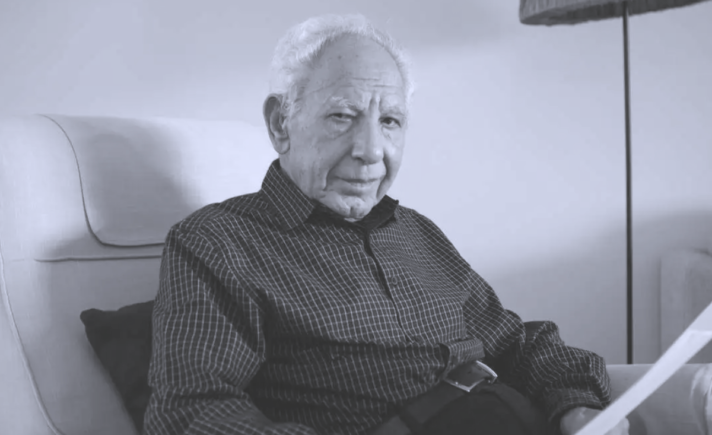

With your abduction and disappearance for more than six years now, I have experienced the worst that any man can experience. It has also been the most unusual of all the many crimes and brutal acts committed in our world. We were not—you and I, specifically—strangers to unusual harshness in our country, which offered some of the harshest and most unusual forms of life in the world overall. Yet, Sammour, nothing could possibly be worse for me than your absence.

When we were arrested in our early youths, we—you and I—were aware of people who had gone through the same experience. We were, to an extent, prepared for it. Arrest was always a strong possibility; a price likely to be paid for undertaking what we believed was our duty. There was art and literature about political prisoners, and their image was highly positive.

To this day, I have found neither art nor literature about forced disappearance, or more specifically people whose loved ones have been disappeared. Even with prison, one finds very little written from the perspective of the prisoners’ relatives or loved ones. Yet the prevalence of the prison case meant those of us involved first-hand grew close to inmates’ relatives during their years of imprisonment. Our own relatives were among them, as were many friends. As for the prison experience itself, it became relatively well-understood due to the writings of previous prisoners, including your husband and others you know personally.

Few, if any, people returned from “forced disappearance” in our generation. I don’t know if there are first-hand testimonies in this regard, and even if there are, it’s unlikely they would address the experiences of relatives; especially of mothers and wives. Historically, in our country, the disappeared were men, and women were the bereaved. My mother was one of them, as was yours. Mine departed us in the years of my small absence, while yours did the same during your large absence.

Today, as in previous Syrian generations, bereavement is a fundamental part of the experience of being a woman, since most of the deceased are men. From the little I know of other countries, in Turkey a group of mothers gathers every Saturday—the “Saturday Mothers”—in Istanbul’s Galatasaray Square to demand information about their sons and other male relatives forcibly disappeared since the 1980 military coup. In Argentina, the mothers of los desaparecidos, taken in the ‘70s and ‘80s by another military regime, would congregate every week for years in Buenos Aires’ Plaza de Mayo; hence their name, Las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo. In Morocco, there was a movement active in the early 2000s concerning those disappeared in the “Years of Lead” between the ‘60s and ‘80s, but it was seemingly less organized, and the authorities were able to shut it down. Our case is more complicated, Sammour. In our generation, there was only one disappearer—the Assad regime—whereas today the disappearers have multiplied: we have the regime; its militias; ISIS; Jaysh al-Islam; and many others. It’s said there are now 98,000 disappeared Syrians. For relatives inside the country to work openly against the disappearers is impossible. On the outside, such work as takes place is scattered geographically.

As a result of this lack of written work—testimonies, stories, poems—it’s not possible to speak of a “disappeared literature” in the way we speak of prison literature. In consequence, I’ve found nothing of help in dealing with this experience. The closest I had to a reference was my own mother during my, and then my two brothers’, disappearances. I call these merely “small” disappearances, since at least she knew where we were, and could visit from time to time. In your absence, I identify with my mother, and with all mothers of disappeared sons. I’ve become a mother to my disappeared wife; to you, Sammour.

Your absence has feminized me, by subjecting me to this feminine experience. Throughout these more than seventy months, I’ve been astonished by the cruelty and horror women are forced to bear, especially since only few of them are able to involve themselves in activism for the sake of their imprisoned or disappeared loved ones. Rarely is it possible for them to turn their anguish into a public cause. When they themselves are prisoners—and, in not a few cases, victims of sexual violence—an even smaller number of them are able to publicize or portray their experiences in any way, while some have been disowned by their families, or even killed to preserve so-called “honor”—“washing” away the “disgrace” by an act of unwashable disgrace.

There is no equivalent experience for men.

I’ve been able to follow your cause, with the help of friends, yet I still don’t feel I have the strength, firmness, or courage of my mother. How was she, and many other mothers, able to bear so much sorrow for so many years? I find it astonishing, especially since many of these mothers possess none of the tools—words written or spoken, images, lines, or melodies—that could aid them in portraying their painful experiences, or presenting them in public spaces, so as to receive solidarity and partnership. In the absence of such tools, the absence of people is multiplied, or absolute. It’s made worse still without the organization that brings relatives closer to one another and sustains them.

Perhaps tears help. They help women more than men, because men learn at a young age to repress them. I was no different. When my mother departed, I hardly wept at all, and was angry at myself in consequence. I needed to cry, but couldn’t. Since your absence, I’ve changed. How much I’ve changed…

I resisted breakdown by various means, Sammour, including tears. I can’t say I’ve experienced what my friend Souad Labbize says about tears; that they have a “poetic function,” one which “revives a broken face.” To me, tears make up for a lack of words, or a failure of words. They rectify the impotence of words, when the latter are unable to portray experience, as though the tears were alternative or complementary words. Perhaps women cry more because they are more deprived of speech, while men cry less because they possess speech more.

Another upshot of this transformation of mine is I hardly have any heroes now who aren’t women, unlike in previous years.

For some time now, the feminist slogan “the personal is political” has summarized my experience, even before I came to know that one of my intellectual heroes, Hannah Arendt, saw in it a defining condition of refugees. In our situation as refugees, the personal and political are condensed together. I’ve seen no problem in the word “refugee,” Sammour, unlike the German Jewish scholar who sought refuge in France for several years before settling in the US for the rest of her life. The word in which I’ve been unable to recognize myself is “exile,” and its derivatives. I try today to find a position for myself between the words, and I both succeed and fail.

As for your position, entirely absent for over six years, I find no words to describe it. Perhaps we need the language of theology to depict your prolonged, silent absence. The personal here is political-religious, and the political-religious is personal. This is a door to a large discussion, one which has opened and I hope won’t be closed any time soon. There isn’t much in the historical experiences of religion that may be compared to our general experiences in the revolution years, nor to our personal experiences since your disappearance. On this it’s possible for important things to be built; new and liberating beginnings.

The experience has changed me, Sammour, and you know I’ve always wanted to change. If it’s still nonetheless been one of the worst things any man can experience, this is not for any macho considerations to do with “protecting my woman” or “pursuing my enemies to the end” but rather because I know this totally unexpected experience was harmful to you, and that what helped you bear five months in Douma after I left was the thought that it would all soon be over, and together we would live, at last, “a life like life.”Referring to a line by the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish: “All that we dreamed of was a life like life.” Your pain regarding the unexpected and dreadful is what torments me and fills my heart with agony. It’s for that pain that I act to be a host and equal—and a narrator.

What I didn’t realize in the past was that change is, for the most part, a tragic experience. The first change didn’t only take lengthy years in prison from me, but the life of my mother too. The price of my change today has been to live as a refugee, and then for you to disappear almost immediately afterwards. A woman gave me her life, her presence, and her freedom, in order for me to change twice. I sometimes think, Sammour, that I pay the terrible price of my craving, of my deep internal desire to change anew, to live a third life. Two lives were not enough for me. The tragedy came from what appeared to be the depth of my freedom and renewal, from a fate I fondly carried with myself; a fate “written on the forehead” in one way or another.

For as long as you remain absent, I will work to ensure that the change for which you pay the price—without my being able to help—is a truly transformative change, one of wide-ranging meaning and freedom, bringing life to others. You and I have no children; perhaps our contribution to public change might be the progeny we leave for those after us.

I say “our” contribution, because you are present and part of it at all times. You are its hero and impetus, because my commitment as a changer, and as a mother to you, is to work for your absence to be a public force for change; living, meaning, remaining.

[Editor’s note: This article was originally published in Arabic on 19 October, 2019.]