Reading Lebanon: A Country in Fragments by Cambridge University’s Dr. Andrew Arsan feels like reading a socio-political biography of the country’s millennials, myself included. My mother was pregnant with me when the Syrian regime bombed our home, and shortly before I was born the Lebanese government passed an amnesty law forgiving most crimes committed during the fifteen-year-long war. I was 9 when Israel was forced out of Lebanon; 14 when Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri was assassinated and I went to my first protest opposing Syrian troops’ presence in Lebanon; 15 when Israel bombed Lebanon (again); 17 when Hezbollah took over parts of Beirut and Mount Lebanon; 20 when the Syrian revolution started; and 24 when I took part in the “You Stink” protest movement as an organizer in its early phases. The latter was also when I left Lebanon, first temporarily and now who knows. Today I am 28, a reluctant member of the diaspora who only visits Lebanon when I have to, though I am currently writing this from my childhood home in Mount Lebanon.

I mention this because I don’t think it’s possible for me to fully dissociate myself from this review, nor do I believe it would be better for me to do so. At the time, I thought my childhood was like any other, though, in retrospect, I think the kid who celebrated his 14th birthday the day the author and democracy activist Samir Kassir was assassinated must have known things were not normal. I don’t know. Like many members of my generation, Hariri’s assassination was the turning point. Of course, those who lived under Israeli occupation until 2000 have never really known normality. For us, unlike our parents, Hariri’s assassination didn’t evoke memories of the civil war because we never lived it. We did, however, feel the tension throughout the country. I remember being in school when it happened. Despite being several kilometers away in Collège des Sœurs des Saints Cœurs Ain Najm, we felt the explosion, and saw the smoke rise out of Beirut. I remember us students watching the film West Beirut when it happened, and I remember being near one of the many car bombs that followed it. At least, I think I do. My subsequent dive into memory studies has led me to cast some doubt on the accuracy of my own memories. Were we watching West Beirut on the same day, or was it before or after? How far was I from the car bomb?

For these reasons, Lebanon: A Country in Fragments has had a sort of therapeutic effect on me. Perhaps that’s why it took so long for me to actually write this review, despite reading the book in 2018, and why a second read was needed. In the thirteen years that Arsan looks at—2005 to 2018—Lebanon has had thirty-four months without a president; a war which left over a thousand killed in 30 days and displaced a quarter of its population; forty-eight separate bombings and twenty-one assassinations or assassination attempts, mainly targeting anti-Assad figures; a potential civil war; conflicts between religious sects, the army, Hezbollah, and/or Syria-based groups; and over a million refugees fleeing the violence in Syria. These are the thirteen years that have followed the Cedar Revolution of 2005 which forced the other invading army, the Syrian one, out of the country.

With this in mind, the most compelling idea in Arsan’s Lebanon is that the country is, actually, not that extraordinary. After all, the intersection of neoliberal economics, the rise of populism and its xenophobic sibling, economic precarity and public disillusionment is hardly specific to the country. This is not how Lebanon is often portrayed, however, whether in the media or in academia. The tendency to resort to various deterministic interpretations is often taken for granted, be they of the sectarian or geopolitical kind, or indeed both, reflecting wider tendencies of looking at the region, including by its own inhabitants. Some sections of the left might resort to economic determinism as well, downplaying the ways politicized identities can either transcend or reinforce class structures depending on a variety of factors. Arsan’s book proposes a different route. He seeks to “map out the landscapes of everyday life,” a history of the present which inevitably includes the anxieties of the past and the future. His main argument is that Lebanon matters because “it is a microcosm of the contemporary world, a Petri dish in which we can observe the microbial strains of late modernity.” How so? The following extract, best quoted in full, lays it out:

“From the glinting lures of populism, with its dual illusion of government for the people, by a man of the people, to populism’s obverse, technocracy and its fantasies of an antiseptic world of expertise, cleansed of inconvenient political realities; from the strains put on the social body by mass displacement, to policies that foster inequality and precarity in the name of perpetual growth and the exhausting sense of living in a time of permanent crisis—so much of what seems to characterise our contemporary condition can be found in Lebanon. By concentrating, if even for a while, on this small country, we can better understand the workings of those techniques of government, those dispositions and ideologies, those bundles of words and practices and sentiments that frame the way we live now. And perhaps nothing defines our contemporary predicament more than the sense of living in a permanent present.”

Arsan, Andrew, Lebanon: A Country in Fragments, Hurst & Company, 2018, p.4.

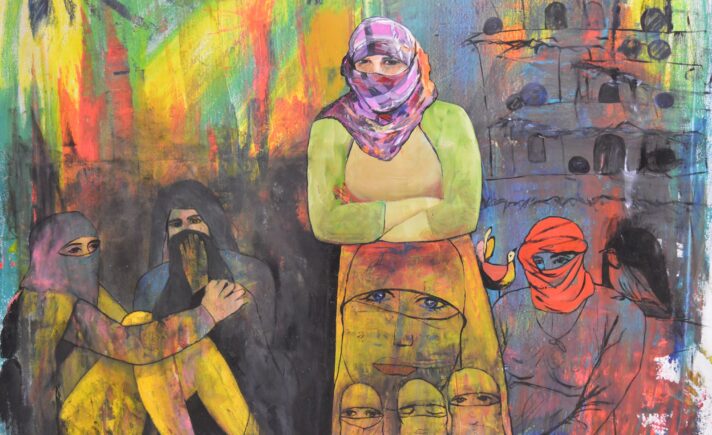

Lebanon seeks to understand, and explain, Lebanon on its own terms. Only by doing that can the story of this complicated country be fairly told, and this book is, if nothing else, fair. It doesn’t shy away from Lebanon’s most horrific, poorly-kept secrets, such as: the conditions of quasi-slavery that hundreds of thousands of domestic migrant workers are forced into under the country’s notorious Kafala (sponsorship) system; the Syrian migrant workers and refugees who have repeatedly built and rebuilt the country while Lebanese parties participate in its destruction, and while all the other parties demonize them; the Palestinian refugees who are no less unfortunate despite sharing the same land for the near-totality of Lebanon’s history; the neoliberal capitalist elites who have rebuilt a war-torn capital, turning its city center into a ghost town while privatizing every inch of public space left (“founded on an understanding of the citizenry as an aggregate of atomised consumers”) and made the country more accessible to Gulf Arabs than to the country’s own residents; its opportunistic, clientelist networks of warlords-turned-politicians and their associates that reinforce sectarian divisions and unite against secular and democratic alternatives whenever convenient; its disoriented/ing and exhausted/ing civil society that continues to try and change a remarkably persistent system while struggling to untangle itself from class and nationalist distinctions; its ever-worsening environmental crisis that may threaten the country’s very existence; and even its famed nightlife and constant obsession with sexualizing women in an already deeply misogynistic political culture, not to mention the dangers that toxic masculinities pose to women and/or LGBTQs.

Unusually, and to Arsan’s credit, the book also shows that Lebanon’s ongoing crises cannot be understood without also understanding the dynamics of its bigger, more brutal sibling, Syria, and the criminal dynasty that has been ruling it with an iron fist for nearly five decades, as well as that of the country’s southern neighbor, Israel, and its militaristic and settler colonial politics against Palestinians. In addition to the 1982-2000 Israeli occupation, the post-1990 era under Syrian ‘tutelage’ turned the country into little more than a puppet state until 2005, leaving it with a generation of Syrian-trained mukhabarat (in effect, secret police) who continue to intimidate activists to this day. This helps understand why Lebanese history, and particularly its civil war past, is often framed as though the country is but a mere stage upon which the world’s actors play out their battles. But while there is no doubt that regional and international powers have a sizeable influence, that influence cannot explain alone how and why Lebanese actors have regularly put themselves at these powers’ disposal.

Where does that leave us? Is there any point in hoping things can change in Lebanon, or are we doomed to live in a country that seems to share all the characteristics of a war-torn one without actively being at war? These questions are difficult to answer, as currently the closest thing to optimism in Lebanon is of the “blithe inhumanity and seemingly endless resources of Panglossian” variety that some appeal to when talking of the devastation in Syria and the apparent economic opportunities offered by “reconstruction.” There may never be enough irony in this world to accommodate the fact that many in Lebanon are now talking about “reconstruction” in Syria after both the Assad regime and the Lebanese government spent over a decade saying the same thing about Lebanon. And if that wasn’t enough to lose hope, one need only be reminded of how frequent it is for commentators and policy makers from Tel Aviv to Washington to speak of the inevitable upcoming Israeli war on Lebanon, or indeed of how normalized a more general anticipation of violence is in Lebanon itself.

The picture is a grim one, and Arsan doesn’t mince words in describing the country. Instead, he inserts the many modes of resistance that people in Lebanon engage in on a quasi-daily basis, interspersed between the many more social pressures to conform. The symbolic violence, to use Bourdieu’s term, inflicted by these social structures—and sometimes actual violence, particularly towards women, people of color, refugees and/or LGBTQs—is dependent upon a self-sustaining system that benefits a fragile and transnational upper class, itself deeply embedded in these structures even when not in full control of them. To see the modes of resistance, however, one must be equipped with the willingness to understand personhood in Lebanon as, in the words of anthropologist Suad Joseph, relational. As Arsan writes, “individuals are never bounded entities, independent of others, but see themselves—and are seen—as bound up in a complex, tight skin of interpersonal relations, which define, sustain, and constraint them.” Therein lies the most accurate framework to understand modern society in Lebanon. These interpersonal relations are more often than not repressive in the sense that they are more likely to create obstacles than opportunities: “Lebanon’s citizens are drawn inexorably into an uneven force field of obligations and constraints, which differ according to their confessional status and the varying legal regimes to which they are perforce submitted.”

Only then can we see the significance of what women’s rights activists, to choose one example, have managed to achieve in the past few years. In Lebanon, political sectarianism and patriarchy work hand-in-hand. Lebanese women are restricted on everything from marriage to inheritance, divorce, and custody, to varying degrees depending on religious sect. In response to the women-led campaigns for the right to remove one’s confession from civil registers, the State made clear it would always treat us as belonging to one or another of the recognized sects, with no departure possible. The only option to escape one sect is to convert to another one. This reveals a deep-seated worry among most politicians in Lebanon. They are unable to control a democratic society which views individuals as having agency, at least in principle. This is why, despite all the difficulties laid out in Lebanon, it remains a book that can serve as a manual for those in Lebanon wishing to understand their country better in order to change it.