[Editor’s note: This investigation has been nominated for the 2020 Samir Kassir Award for Freedom of the Press. It was originally published in Arabic on 16 May, 2019. The reporting was carried out with the support of the Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism (NIRIJ), under the supervision of Kami al-Melhem.]

13-year-old Hibatullah stood in a long queue with a group of women waiting for bags of rice and pasta to be distributed by a charity in eastern Aleppo’s Bustan al-Qasr neighborhood. She held up the hem of her black dress as she walked so as not to stumble. Perhaps she had borrowed it from her mother’s closet, or received it from a clothing donation campaign. This was in mid-2016, while east Aleppo was still under the control of Syria’s opposition factions.

In the scorching forty-degree heat, Hibatullah failed to find her name, or her mother’s, on the charity’s list of beneficiaries. Asked to leave the queue, she sat on the sidewalk and fell into a fit of sobs. Her posture and gait revealed the roundness of her belly, and the pregnancy she tried to hide from those around her. Turning to this writer, sitting next to her, the girl said her only brother was an Islamic State (ISIS) fighter in Manbij, to Aleppo’s northeast. Now wailing, she added that her brother had married her off to his Saudi commander, which was how she had ended up pregnant.

“I know nothing about my husband; not his real name, nor his family, nor even his whereabouts,” she said. They had only been married a few months when the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) entered Manbij, and her husband escaped, leaving her and her mother to face their fate alone. A child pregnant with another child, Hibatullah and her mother then returned to Aleppo.

The fabric covering Hibatullah’s head slid down, and she hastened to wrap it around her again, revealing only her weary face and tired green eyes. “I wear loose clothing so people don’t ask me about my pregnancy,” she says. “I don’t want to be ridiculed.”

That was how we met Hibatullah. After our brief encounter, we kept in touch by phone, and we learned that she carried the child in her womb throughout her forced displacement on one of the infamous green buses to a camp for internally-displaced persons (IDPs) in Atma, on the Turkish border, in late 2016. There, she gave birth to her daughter Farah, and began seeking a way to register the newborn in the civil records.

This is the story of many children born to legally-unidentified fathers, and mothers who married foreign fighters, in a social and legislative environment that refuses to recognize such marriages, and in some cases even considers these children to be “terrorist bombs” or “the fruits of extremism.”

Jihadist matchmaking

The year 2012 saw dozens of foreign fighters arriving in Syria, often individually and in a disorganized manner. Upon entering Syrian territory, these fighters initially joined the rebel factions that existed at the time. By the end of the year, there began to emerge brigades with Islamist, Salafist, and/or jihadist leanings, some of them linked to al-Qaeda, such as Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS, before the latter broke away. Other groups adopted al-Qaeda’s ideology without formally pledging allegiance to it, such as Jaysh al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar, Jund al-Aqsa, and the Turkistan Islamic Party in Syria.

By mid-2015, more than two thirds of Syrian territory was controlled by these armed groups, particularly ISIS and al-Nusra, now known as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). As they grew, ever-larger numbers of non-Syrian fighters flocked to the country.

“Some brought along their wives, but as their stay lengthened, and they began to live in relative stability, most started seeking wives from the areas they controlled,” says Asaad al-Mahmoud, a researcher based in Idlib. “The jihadist aura that was associated with them; the money they brought with them or obtained as spoils of war; and the positions they held all attracted no small number of women to marry them.”

Jihadist organizations would often send “matchmakers” to residents’ homes, knocking on doors looking for girls old enough to wed, according to multiple eyewitness accounts. One such “matchmaker” was a woman who used to find wives for foreign HTS fighters in the rural villages south of Idlib. She said she met a number of fighters through her son, who had joined the group, and that she found them to be “well-mannered and keen to get married.” She added, “I know most of the girls in my village, and I chose for [the fighters] women from poor families; or older women; or widows or divorcees.”

Crucially, most of these marriage contracts were carried out using the husbands’ noms de guerre, rather than their legal names, added the woman, who asked to remain anonymous.

Syria’s eastern provinces appeared to be where marriages to foreign fighters were most prevalent. Areas such as Raqqa, Deir al-Zor, and the countryside east of Aleppo saw more children born of unconfirmed parentage than other places that weren’t under jihadist control, such as Azaz, Marea, the Hama countryside, and the villages west of Aleppo, according to the researcher al-Mahmoud. As for the areas still controlled by HTS to this day, marriages to foreign fighters continue to occur.

A dangerous environment

In a dangerous environment, where residents are forbidden to talk to the press, obtaining even a rough estimate of the number of children born to unrecognized parents is a challenge. This report draws on four months of meetings with judges, civil servants, and local councillors, as well as a survey in several areas in northern Syria conducted with assistance from humanitarian organizations.

Al-Jumhuriya obtained tables documenting the names of 1,826 children in Idlib and its surrounding countryside, as well as the provinces north and west of Hama, collated by a campaign titled “Who Is Your Husband?” The tables were provided by Muhammad Nur Hamidi, a former judge and regime defector active in the campaign. Most of the areas in question were controlled by HTS at the time of writing. The data indicate these children were born of 1,124 out of 1,735 recorded marriages.

It ought to be noted that Judge Hamidi was kidnapped shortly after providing us with the data, though he was subsequently released in exchange for a ransom.

In the countryside north and east of Aleppo, where Turkish-backed “Euphrates Shield” militants currently predominate, the investigation team spent four months interviewing members of local councils; civil registry employees; and judges in the three largest civil courts—those of al-Bab, Jarabulus, and Azaz—as well as other courts in Marea and al-Rai. The team also compiled documents related to attempts to confirm family lineages, and surveyed relevant cases in IDP camps. By reviewing the names collected, and excluding duplicates, the team found there were approximately 1,000 children of unrecognized parentage in these areas. An additional 1,000 were estimated to exist in the west of Aleppo province, where HTS seized control from opposition factions Nur al-Din al-Zenki and Ahrar al-Sham in early 2019.

Unfortunately, when it came to Raqqa and Deir al-Zor, the team encountered great difficulty gathering information or making estimates with any degree of accuracy. These had been ISIS’s key strongholds, in which the largest number of foreign fighters resided, before the US-led Coalition and SDF overthrew the jihadists’ rule.

Due to the infeasibility of entering these areas, and our inability to obtain permits from the SDF, the investigation team instead decided to survey camps housing IDPs from Raqqa and Deir al-Zor in Idlib governorate.

Over 4,000 children

On 27 November, 2018, we obtained the necessary permits from the Ministry of Justice of the so-called “Salvation Government,” and from Public Prosecutor Muhammad Qabaqabji. We contacted IDP camp administrators in Sarmada, north of Idlib, to conduct field visits and meet with women who had mostly come from Raqqa and Deir al-Zor.

This “Salvation Government” was established in early November 2017, operating in areas controlled by HTS across most of Idlib, rural Hama, and the countryside west of Aleppo. It is widely understood to be the civilian face of HTS, even if it officially denies links to any armed faction.

As the investigation team arrived at the camp administration center, seeking access to a camp in the village of Khirbet al-Joz, on the Turkish border west of Idlib, one member was apprehended and detained by a group of HTS gunmen. He remained in their custody for four weeks, during which he was interrogated on espionage charges, and his mobile phone and camera were confiscated, before he was eventually released through personal connections.

We later learned from sources inside the camp that it was home to over 350 cases of marriage to unrecognized persons.

This journey through multiple areas fought over by various military factions resulted in the documentation of more than 4,000 children of unconfirmed parentage across northern Syria. An additional 4,000 women and 8,000 children born to foreign jihadists are located in three camps in parts of the country’s northeast controlled by the SDF, according to Kamel Akef, a spokesperson for the Foreign Relations Office in the Autonomous Administration responsible for the territories in question. These women and children reside in designated sections of the camps, and are subject to tight security surveillance and control.

According to al-Mahmoud, the Idlib-based researcher, the true number of children born of undocumented parentage likely exceeds the above figures, “if we add other exceptional circumstances, such as women married to unidentified Syrians or those without civil records, and widows afraid of documenting their marriages since their husbands are linked to ISIS or other Islamist factions.”

“Who will marry my daughter?”

Of 25 women who married foreign fighters in 2014, seven returned to the town of Bashqatin in the countryside west of Aleppo. One of them is Amina, the 30-year-old wife of Abu Omar al-Misri, a fighter in the Usbat al-Ansar Brigades who later joined ISIS and moved with Amina to Raqqa.

In late 2017, Amina stood before a judge in the court of al-Qasimiya, 15km west of Aleppo, hoping to be legally recognized as a wife. She held a worn-out piece of paper containing neither her husband’s legal name nor those of the witnesses. “This is all I have, and the judge did not recognize it,” she said, before carefully folding the marriage contract back into a plastic bag.

At the time, the court was affiliated with the Nur al-Din al-Zenki movement. When control of the village then passed into HTS hands, Amina says she lost all hope.

The situation appears even more complicated for Thuraya, a 33-year-old from the village of Anjarah west of Aleppo, and a mother to four children from three marriages. After her first husband—an ISIS member who was also her cousin—was killed in Raqqa in 2014, she married a Libyan fighter, with whom she had a son. When this second husband was killed, ISIS married her off to a commander whom she said was once a Russian officer, with whom she had her youngest daughter, now two years old.

As for her two sons from her initial Syrian husband; 9-year-old Ali and 7-year-old Muhammad; they do not attend school, and a similar fate may await her third son, now four years old. Thuraya’s greatest anxiety, however, is for her youngest daughter. “In the eyes of the law, I am unmarried,” she said more than once during our interview. “I don’t know the name of my husband, and I didn’t even speak his language. Who will marry my daughter when she grows up?”

Thuraya followed all the procedures required at al-Qasimiya court, yet her children remain without established parentage. This has affected her ability to obtain humanitarian aid. “Every time I contact aid organizations, they ask for family records or a family ledger, but the civil registry has not issued me any documents confirming my marriage.”

Data obtained by the author indicate that 260 requests for marriage confirmations have been filed in al-Qasimiya court alone. In the city of al-Bab, east of Aleppo, 90 lineage confirmation requests were filed, 16 of them involving non-Syrian Arab or European husbands. Idlib’s main court declined to disclose its number of equivalent cases.

As for the Jarabulus court, more than 100 such unresolved requests have been filed, according to Muhammad Ayman, the head of records at the court, who said fear of prosecution prevents hundreds more women from filing similar petitions. “The camps are filled with such cases,” he told Al-Jumhuriya.

Three separate laws

Courts in the areas controlled by opposition factions recognize as many as three distinct sources of legislation, depending on the particular group regnant in the area. Courts in the so-called “Euphrates Shield” region, for example, use Syrian law with certain amendments, while those in the rural areas west of Aleppo (at the time of writing) and certain parts of Idlib not under HTS control use what is known as the Unified Arab Law. As for HTS and other Islamist factions across Idlib, they enforce their interpretations of Islamic law.

For all their differences, the courts agree on not recognizing marriages to unidentified persons, or confirming the lineages of children born to such marriages, according to Zakaria Amino, a lawyer working in courts in Idlib and the countryside west of Aleppo. This was corroborated by another lawyer, Abd al-Aziz al-Darwish, who has represented a number of women in cases filed in western Aleppo Province. “Women do not get the results” they’re looking for, he says.

As for the eastern and northern countrysides of Aleppo, which are under the control of Turkish-backed “Euphrates Shield” factions, the courts there refuse to confirm parentage without a complete set of identification documents for the husband, according to Muhammad Adib Kersho, a judge in the courts of Azaz and Marea, as well as Muhammad Haddal, a judge in the Suran court. “A woman has no right to submit a request using [her husband’s] nom de guerre; the law does not permit this,” said the latter.

An exception was Muhammad Qabaqabji, the public prosecutor in the “Salvation Government’s” Ministry of Justice in Idlib, who said he regarded these marriage contracts as valid. “As long as the husband is known to some people, and his location and description are known, it is not a requirement to know his legal name,” said Qabaqabji, just days before being assassinated by an explosive device on 22 March, 2019. Qabaqabji claimed his senior, the “Justice Minister” Ibrahim Shasho, shared this opinion, though the “ministry” has taken no action to resolve the cases that have been filed.

According to Muhammad al-Ahmad, an Islamist researcher from Idlib, a verbal agreement was reached between the city’s dignitaries and the “Ministry of Justice” to confirm marriages and lineages involving unidentified persons. Per this agreement, a wife was required to file a judicial claim, attaching a certificate of identification for the foreign fighter, recording his name or nom de guerre, corroborated by two witnesses and stamped by the faction to which he belonged. “It was agreed to open a new record in the civil registry for foreigners, so that children would be recognized as descending from their fathers,” says al-Ahmad. “If [the father’s] name were unknown, [the child] would be named after their father’s country; e.g., ‘the son of the Egyptian’ or ‘the Iraqi’.” This agreement seems never to have actually been implemented, however: a personal status judge in Idlib, Omar Abd al-Qadir, told Al-Jumhuriya, “We do not accept filings that do not use real names.”

“Permissible but sinful”

Most of the judges, lawyers, and employees interviewed were sympathetic to the wives and children of foreign fighters. It was not uncommon for their religious jurisprudential opinions based on the fatwas of clerics to be mixed with those derived from civil law.

The head of the Idlib lawyers’ syndicate, Abd al-Wahhab al-Daif, opposed the registration of children born to unknown fathers, decrying the “great sin and a social crime committed by the fathers who agree to marry off their daughters in this way.” A child’s parentage could not be confirmed before their parents’ marriage itself was established, he said, adding that such a marriage was “not permissible, because it is a marriage of ignorance, and to be ignorant of the identity of either spouse in the contract is religiously forbidden.” According to him, this opinion was based on a fatwa issued by the Istanbul-based Syrian Islamic Council.

In fact, the fatwa in question describes such marriage contracts as “permissible but sinful,” due to the “harm and damage done to the wife, in social or civil terms.” A child resulting from such a marriage is a “legitimate child,” according to the fatwa, which adds that if the unknown father belongs to an “extremist group,” then it is “preferable” that the marital contract be forbidden.

In short, then, most of those interviewed agreed that marriages involving unidentified persons were illegitimate, whether in areas controlled by HTS or the “Euphrates Shield” zone. A minority considered the marriages valid but “objectionable” (makruh). As for Syrian civil law, it regards such cases as “categorically null and void,” according to Judge Muhammad Nur Hamidi, who said it was obligatory for spouses’ real names to be known and identified.

Prayer, then suicide

In a camp in the village of Deir Sarhan, west of Aleppo, a woman in her fifties lives with her three-year-old granddaughter in a tent containing only a gas stove for cooking, two mattresses on a plastic mat, and a few pillows.

In June 2018, Umm Hamida awoke to find her 21-year-old daughter dead in a prayer robe. Next to her was a Qur’an and three empty boxes of blood pressure and diabetes medication.

“Her face was wet with tears, even after her death,” the woman recalled, holding her granddaughter to her chest.

According to Umm Hamida, her daughter committed suicide after incessant harassment from her relatives. “They used to call her an ‘ISIS wife,’ or an adulteress.”

“Hamida believed in God,” her mother continued, but poverty and harassment drove her to end her life. “In the tent, I found a dinner plate and a cup of coffee. Before she died, she ate and drank coffee, read the Qur’an, prayed, then took the medicine.”

Hamida was not the only wife of a foreign fighter to take her own life; we heard similar stories across multiple regions. Most of these women used medication overdoses, or the infamous so-called “gas pill,” which can be bought from a corner shop and is used as a pesticide for agricultural crops.

“What crime have these children committed?”

By the end of 2018, there were 36,356 widows and 189,924 orphaned children in Idlib and Hama, according to the Northern Syria Response Coordinators team. Between 2011 and August 2018, some 13 million Syrians were displaced; more than 6 million of them to elsewhere within the country, according to Pew Research Center data. In northern Syria, most families in need seek aid from humanitarian organizations. Yet this is not an option for families with children of unrecognized parentage.

After escaping ISIS and returning to al-Bab in 2016, Umm Taha now lives with her two children in a camp on the Turkish border, lacking any official documentation and thus deprived of access to aid and the opportunity to educate her children. Looking at her eldest son, who is now of school age, she laments his future. “The camp administration refuses to sponsor the children or give them aid, so my boy Taha cannot enter the school.”

At the age of 30, Umm Taha married an Egyptian judge in the ISIS court in al-Bab. They had met in 2013, when she filed a suit against her abusive brothers, whom she said treated her like a “servant,” and beat and insulted her. After repeated visits from the judge, on the pretext of checking up on her and her brothers’ behavior, she ended up marrying him, finalizing the contract in his court, using his nom de guerre.

The rules governing humanitarian organizations forbid the provision of aid to people of unestablished descent or those without official papers, according to Ahmad (a pseudonym), an NGO official in al-Bab.

“There are strict instructions against this, but we often defy them for humanitarian reasons,” he tells Al-Jumhuriya. “What crime have these children committed?”

Sara Salah is a mother of three, all of whom also lack official documentation. She married a Tunisian fighter at the request of two of her brothers, who were ISIS members. Both were killed in the 2016 Battle of Manbij, while the SDF captured her third brother.

“I tried to obtain a paper from the civil registry, or to file a claim to confirm my marriage so I could put my children in school, but to no avail,” she says.

Most children of unrecognized parentage are under the age of six, and so not yet old enough for school. Nonetheless, “the issue requires an urgent resolution,” says Faysal Darwish, head of the Aleppo Education Directorate. “The directorate is trying to provide all facilities for the enrollment of children in schools.”

“How can we give a student a certificate for completing a stage of education without knowing their parentage or even their surname; when they have no ID papers, nor even a legal nationality?” asks Anas (a pseudonym), an official in an education center. Nor is the issue merely an administrative one. “These students are affected psychologically whenever they’re asked about their fathers, or mocked by their peers in the classroom. Most of them suffer from introversion, or display hostility.”

A counterfeit solution

Umm Abdullah, an Aleppo resident, is a mother to a boy and girl from a Tunisian father. She says she repeatedly attempted suicide while living in Raqqa with her husband, who kept her locked in an underground cellar. She eventually escaped, paying $3,000 to members of the SDF, in order to avoid being arrested along with her children. She ended up in the countryside west of Aleppo, but was unable to get her marriage recognized.

“My husband used to keep his papers in a belt pocket, which he took with him even to the bathroom,” she said.

Eventually, Umm Abdallah managed to obtain a forged family ledger from the town of al-Dana, north of Idlib. She had tried various ways of obtaining legitimate official papers, spending around $300 on a lawyer, but in vain. Thus she resorted to the “quickest and cheapest” method of resolving the issue of her children’s parentage.

For 10,000 Syrian pounds (SYP), or about $20, she acquired a counterfeit family ledger, similar to those issued by the Assad regime. This enabled her to get registered in the civil registry, with a false name for her husband. At last, she can now access humanitarian aid.

Such counterfeit documents have become rife throughout the country, encompassing not just family ledgers but also university degrees, passports, and even death certificates. We found brokers openly working in the forgery business, both in opposition and regime-controlled areas. Others operate on social media.

We contacted one such broker, saying we wished to get a marriage recognized, along with the parentage of two children we said were close relatives. For approximately 200,000 SYP ($400) per child, we managed to obtain a family ledger from a civil registry in regime-controlled areas in just a week. In opposition-held areas, prices were much lower, ranging from 10,000 to 20,000 SYP ($20-40), or even less if the family ledger was not stamped with “original” seals.

Ghiath al-Ali, from the Aleppo countryside, was one victim of this trade in forgeries. Upon obtaining a family record statement, he was surprised to discover he was husband to a second wife, and the father of children he had never heard of before. He is now seeking to sue the woman who “married” him without his knowledge. He laughs as he tells us how he felt when he found out.

“For a moment, I was frightened, especially if my wife found out about it. I was afraid she wouldn’t believe me, with all the problems that would entail. After a while, though, I laughed about it, and wondered why I was chosen, especially since I have never in my life met anyone with the name of my supposed wife.”

A civil registry employee in the countryside west of Aleppo explained that forgers “use records lost from the civil registries during battles, or obtain them using phone applications, or from shops selling and buying mobile phones.”

Fearing legal prosecution, many wives of ISIS fighters have registered marriages to relatives or cousins in order to obtain official judicial recognition. “ISIS wives attribute their children to their relatives in sham marriages, fearing prosecution,” says Muhammad Ayman, head of records at the Jarabulus court. This was corroborated by Judge Haddal of the Suran court, who described these fake marriages as “a serious issue, because of the loss of inheritance and lineage.”

Other women saw traveling to Turkey as the solution. Umm Khalil received temporary ID (Kimlik) cards from the Turkish government for her daughter and grandchildren, whom she attributed to an imaginary father.

“The procedures were easy. All I needed was a forged family ledger, for which I paid about $30, which I then provided to the immigration services along with a home address and phone number. It was not checked thoroughly, and I obtained the card and family number.”

“Terrorist bloodline”

During discussions of a new law for people of unknown parentage in June 2018, the Assad regime’s parliament (officially the “People’s Council”) replaced the term “child of unknown lineage” with the word “foundling,” per Law No. 107 of 1970. According to the legal definition, a foundling is “a newborn who is found and whose parents are unknown.”

The Council approved Article 20 of the draft law, which states that, “The person of unknown parentage shall be considered a Syrian Arab, unless otherwise established.” Article 21 of the same law states that, “The person of unknown parentage shall be considered a Muslim, unless otherwise established.” This law was the subject of intense debate in the Council, and the controversy spread to the public and the press. Some considered the law’s passage to be a response to an urgent humanitarian need, since the children were innocent of the sins of their fathers. Others, however, including Council member Nabil Saleh and the journalist Maggie Khouzam, said the law “grants terrorist bloodlines the legitimacy of official documents” and approves what they termed “sex jihad” (jihad al-nikah). This latter phrase alludes to a rumor that has circulated in Syria since early 2013 in the context of the revolution, attributed to one Sheikh Muhammad al-Arifi, who has denied it. It is widely seen as a fabrication promoted by Assad’s forces and intelligence services in an effort to defame the armed Islamist opposition.

The semi-official Al-Watan newspaper has reported the existence of 300 children of unrecognized parentage in regime areas alone; a figure which cannot be independently verified.

In northern Syria, courts affiliated with local armed factions refuse to allow mothers to grant their Syrian nationality to their children, except either as “foundlings” or “persons of unknown parentage.” Ahmad, for example, did not obtain Syrian nationality, and could not be registered in the civil records, even though his mother got her marriage contract recognized by a court in al-Bab, and provided the father’s Turkish travel document. Ahmad’s mother, whose husband was killed in 2017 in a battle with regime forces, said she was unable to obtain an official family document for her child. When asked why, she gestured with her hands to indicate she didn’t know, and said she wished she had pretended not to know the father’s identity.

“In cases involving marriages to foreigners, the children cannot obtain Syrian nationality,” says Alaa al-Din Abdo, a lawyer in the countryside north of Aleppo. “The judge has the right to grant the child Syrian nationality if their birth is proven to be on Syrian soil. They are then treated as foundlings, placed in special registries, and given a name, surname, and special record.”

As for the SDF-controlled areas in the northeast of the country, officials there demand the return of hundreds of children of unrecognized parentage to their “countries of origin.”

The child who carries a child

The issue of unregistered children in Syria is likely to get worse with time, as it is not only confined to the children of foreign fighters, but also those born of many marriages between Syrians themselves which have for years been transacted through informal, customs-based contracts, rather than in courts and civil registries.

“It is rare for citizens to use the courts,” says Osama al-Khodhr, a civil registry official in the countryside west of Aleppo. “Of the 800 marriages in Aleppo’s western countryside in 2018, only 150 were conducted in court.” Al-Khodhr attributed this to “ignorance,” or fear of accountability and prosecution in the case of wanted persons.

In the areas controlled by opposition factions, no local councils or humanitarian organizations have yet supported programs raising awareness in this regard. The sole initiative addressing the issue has been the “Who Is Your Husband?” campaign, launched in early 2018 by activists in Idlib and rural Hama.

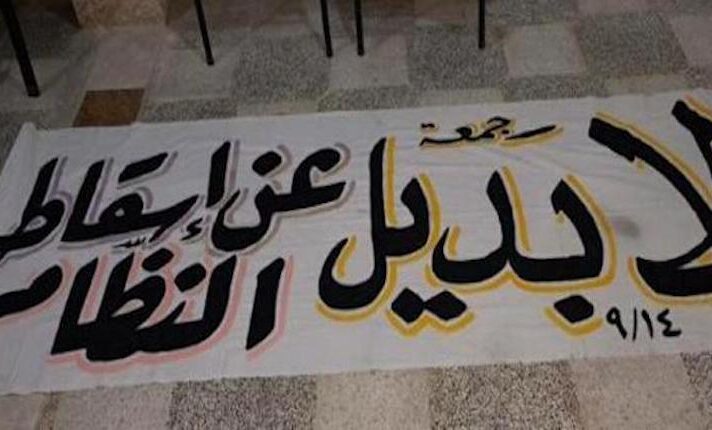

“It was met with hostility from armed factions, and accused of standing against marriage to foreign fighters who came to support the Syrian revolution,” says Judge Hamidi, one of the campaign’s organizers. It involved seminars to publicize the dangers of such marriages, and graffiti calling for the naturalization of the children, bearing slogans such as “I want my children to have a lineage” and “A child with no nationality will have no civil rights.”

Judge Hamidi warns that the failure to naturalize these children and integrate them into society helps the expansion of extremist organizations, especially ISIS, inside the IDP camps, citing examples of “extremists penetrating immigrant families” in al-Hawl and other camps.

“The social stigma that attaches to these families, and the absence of care programs, facilitate the initiation of children into the world of crime and extremism,” says Husam Raslan, a social researcher and teacher at the al-Nur Institute in eastern Aleppo province. He adds that the problem of forged lineages will be a long-term one, potentially beyond the ability of any institution to rectify.

For his part, Panos Moumtzis, the UN’s Regional Humanitarian Coordinator for the Syria Crisis, has called on governments to resolve the situation of 2,500 foreign children detained in al-Hawl camp in northeastern Syria. In a statement in Geneva on 18 April, 2019, Moumtzis said, “Children should be treated first and foremost as victims. Any solutions must be decided on the basis of the best interest of the child,” adding that solutions must be carried out “irrespective of children’s age, sex, or any perceived family affiliation.”

*

Last January, in the Deir Hassan camp in the countryside west of Aleppo, Hibatullah—now 16 years old—sat cross-legged, holding her two-year-old daughter, as passers-by made remarks.

The “child who carries a child” is the nickname given to her by a camp official. She seemed happy to see us again, long after our first encounter. The baby girl, who faltered as she walked, was full of life, and tried to stumble away from her mother’s embrace. Her name contrasted with the experience of her mother since her conception: Farah (“Joy”). Hibatullah’s face, chapped by the cold wind and lack of heating, formed a smile as she held out a document confirming her marriage and Farah’s parentage. She said she obtained it through a lawyer from the Assad regime, and with it she has managed to receive some aid. The documents are doubtless fraudulent, yet they seem to have brought a measure of happiness to a child abandoned to face life’s burdens alone in a cold tent far from home.