“What is really happening is that brother has murdered brother knowing it was his brother. The American people are unable to face the fact that I’m flesh of their flesh, bone of their bone.” – James Baldwin, London, 1969.

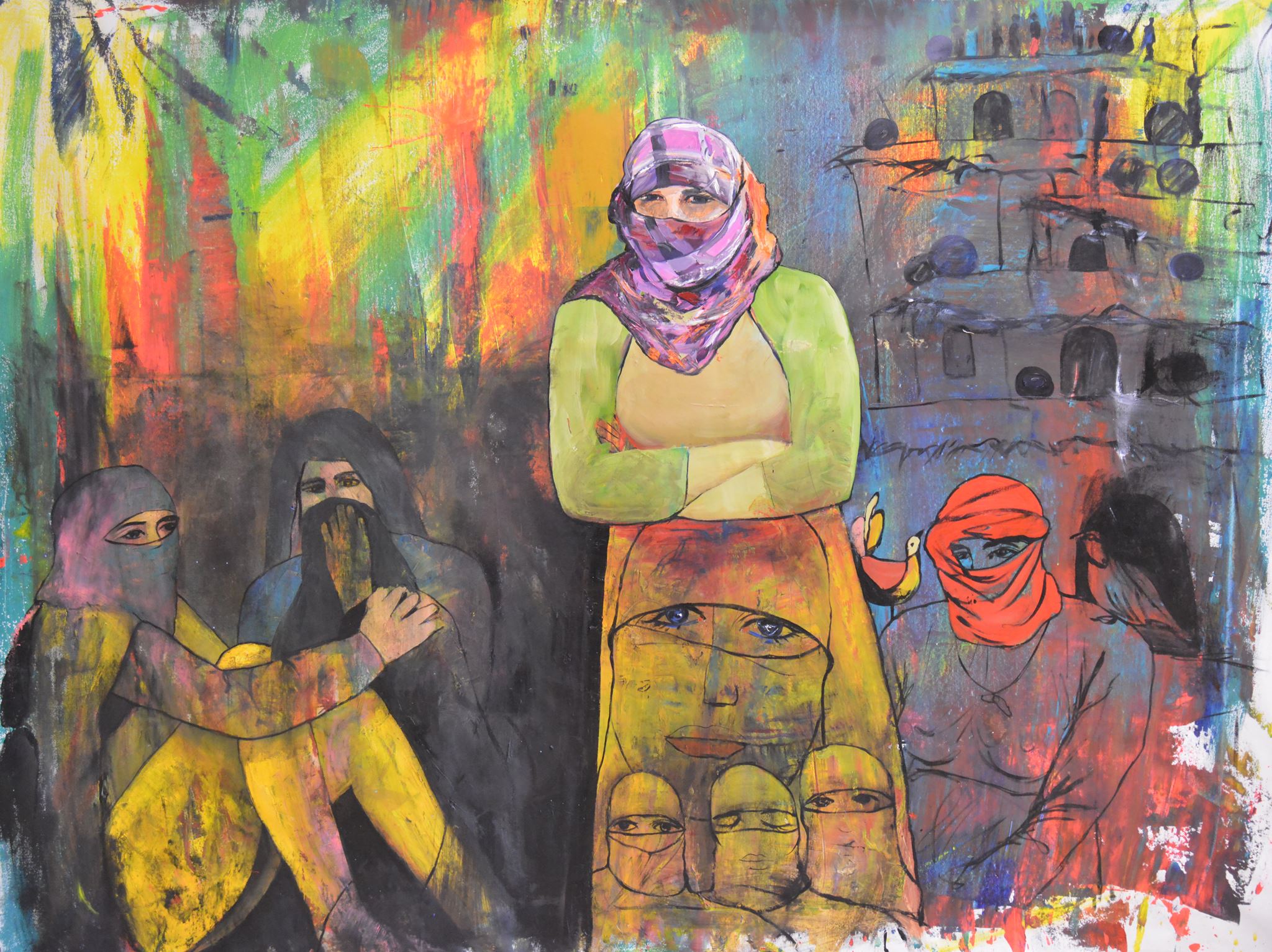

In this essay, I wish to look at the mechanisms behind a certain Lebanese reality: that of “Othering” groups of people with whom we have shared land for decades, namely Palestinians and Syrians. For the purpose of this piece, I will focus on the post-civil-war era from 1990 to the present.

A Baldwinian extrospection

As Palestinians have shared decades of Lebanese history with the Lebanese; the first wave having found refuge in 1948 just five years after Lebanon gained its independence; they have occupied an important position in the Lebanese imaginary, and in the Lebanese sense of themselves. For different reasons, Syrians have also shared decades of Lebanese history with the Lebanese. This is why, as is common with most forms of national identities, a component of “Lebanese-ness” is in the negative: an essential part of being Lebanese is not being Palestinian or Syrian.

At the end of Lebanon’s fifteen-year war in 1990, Palestinians found themselves with little to no political power. With the country’s warlords-turned-politicians agreeing on a formula of “no victors, no vanquished” (“la ghalib, la maghlub“), a formula put in practice by the passing of an Amnesty Law forgiving war crimes committed during the war, the Lebanese found themselves in need of a group of people to blame. This notably took the form of a growing acceptance of the notion that “the Palestinians,” collectively, were responsible for causing the war in the first place, a belief fitting well with the narrative of the war as “the war of others on our land.”

Even during the war, there was already a tendency to excuse or deny our own role in what was happening. It latched onto a widespread cynicism that developed soon after the war started in 1975. For a quick contextualization, and at the risk of oversimplifying, various Lebanese factions repeatedly switched loyalties depending on local and geopolitical circumstances. For example, the Lebanese Forces (LF) initially fought alongside the Syrian regime in 1976 before switching to opposing it and describing themselves as “the Lebanese Resistance.” That even more infamous “Lebanese Resistance,” Hezbollah, which also adopts the mantle of “Islamic Resistance” depending on the audience it is addressing, even fought its current ally Amal while both were vying for the attention and support of the Syrian and Iranian regimes as late as 1990. The rest, as they say, is history, and a victorious Hezbollah continues to dominate politics to this day, with Amal’s leader Nabih Berri rewarded as speaker of the parliament every year since 1992 in what they call a democracy.

On the ground, as some observers noted at the time, the increasing frequency of massacres and wanton destruction created an environment of distrust and fear. “There is no one to admire or trust,” Edward Said wrote in 1986, “in this too long and too sordid spectacle of idiotic violence and limitless corruption.” This lack of purpose, which we may call self-hatred, would be thrown on “the Palestinians” when the war ended, with real-life consequences for refugees. In the words of Bassam Khawaja, “the transformation of refugees in the collective public memory from the role of victim to that of instigator forms the base justification for their mistreatment in postwar Lebanon.”

Postwar Lebanon found its scapegoats because it would otherwise have had to face its own demons. Whatever power was held by Palestinians in Lebanon was effectively lost in 1976, when the Syrian army invaded, and then again in 1982, when the Israeli army invaded. Those crying for the sovereignty of Lebanon, who accused “the Palestinians” of violating it, those who slaughtered and destroyed in its name, oversaw both invasions and were complicit in both.

When the war ended in 1990, Israel was still there, brutally occupying the south, torturing and killing both Lebanese and Palestinians, and would stay until 2000. As for Syria, it maintained significant control over the country’s affairs, having a direct role in key decision-making processes and training our mukhabarat (intelligence agency) to replicate the Assad regime’s brutality in Lebanon. This would last until the 2005 “Cedar Revolution” following Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri’s assassination forced the regime’s army out of the country. Consequently, the murderous giants on their thrones could not be blamed for Lebanon’s ills as they maintained a tight grip on any discursive dissent in the years following the war.

The Lebanese could not be blamed, either. They were now in the business of maintaining that peace built on graves and ruins. The warlords-turned-politicians found it mutually beneficial to avoid any and all mea culpas, even refraining from pointing fingers at former war enemies, despite the fact that some of the most brutal battles were almost exclusively intra-Lebanese. In addition to the aforementioned Amal-Hezbollah rivalry, the notorious battles between forces loyal to now-President Michel Aoun and LF leader Samir Geagea (who “reconciled” in 2016) left many dead in 1990 as well—to name just two examples.

And so, it was those political orphans in the corner, those with no home to go back to, who were blamed.

Baldwinian introspection

When I found out I was the grandson of a Palestinian, this came as a surprise, but not a shock. I couldn’t be shocked because I had nothing to be afraid of. I was a Lebanese Christian. This land was mine, I was told. Everything about it was mine and, therefore, all those living in it were unwelcome guests, especially Palestinians. They were here because we were too good. We didn’t kill them all.

This is how the story was told to me in school by a nun who also told me to love my neighbor as I loved myself. Such is the sectarian historiography that I inherited. It was okay not to seek a solution to the ills of my society because I was comforted from a young age to believe these ills were all imposed from the outside, that they may one day disappear if I wished them away hard enough. And so I tried. I hated Palestinians and Syrians, although I had rarely even met one, let alone known anything about their dreams and nightmares, hopes and fears. I couldn’t be both Palestinian and a Lebanese Christian. One couldn’t be both because if one could then the whole premise of the civil war could not exist. But I am both, and so my very existence betrays a way of making sense of the world that desperately needs to reassert itself through violence, both structural and symbolic, inflicted on “Other” bodies.

Then 2011 happened. While the warlords and businessmen ruling us were engaged in their usual sectarian calculations, our neighbors to the east and north rose up against a brutal regime, the same Syrian regime we rose up against in 2005. I was there, in Beirut’s Martyrs Square, demanding that the Syrian army leave Lebanon. I didn’t understand much at the time, but I knew this was the right thing to do. Yet when Syrians rose up against that same regime, we Lebanese did not rise up with them.

And why should we? After all, as my grandmother told me in one afternoon in 2011, we should instead “remember what they did to us.” Just like that, “the Syrians” joined “the Palestinians” in my mind as faceless, nameless, and threatening. It was around the time the city of Homs was being besieged. Homs was where Homsiyyeh lived. Growing up in an overcrowded Catholic school in a small Christian village, I wasn’t even aware they were real people then. Us boys used to call each other “Homseh” as a byword for “stupid,” the same way we’d call each other “looteh” (equivalent of “faggot” in English). It’s how we reasserted our racialized, heteronormative, militarized masculinity—by showing no sign of weakness or emotion (other than anger, of course).

We knew that Syrians (here imagined as exclusively males) were those who rebuilt our homes after the war, that they did and continued to do so without getting recognition for it. And that was the point. Recognizing their role in rebuilding what we had destroyed with the help of the Syrian and/or Israeli governments would require introspection. And we couldn’t have that. Our masculinity was that of the warlords, the zu’ama, and their business associates. It allowed no room for thought.

The warlords and businessmen continue to calculate to this day. What else are they to do? The alternative is facing the past, and the past is too dangerous. The other alternative is facing the present, and the present is even worse. And so they calculate and calculate. They’ve included their sons in the calculations too, so that they may calculate once they’re gone. Instead of rising up, we sent our young men to go to Syrian homes and kill for that very same regime that we fought against. Well, “not all of us kill for the regime,” I hear some readers say. It’s true. The rest were too busy calculating, you see. But we could all at least agree with the killers on the urgent need to keep Syrians in Lebanese ghettos, those wretched of the Earth who build our homes while we destroy theirs.

In 2011, the Syrian revolution changed almost everything, but not our sectarian calculations. On the contrary, it exposed a very inconvenient truth about postwar Lebanon, namely that the war never ended. Violence lurks at every corner. It comes with us when we’re stuck in traffic, when the electricity cuts off, when trash overflows and spreads. It rises up again when we entertain the theatrics of elections. That is when our militarized masculinities explode in mindless violence, aided by the only thing they truly love: the gun. We call our nameless problems Syrian or Palestinian, but they are as Lebanese as can be. We anticipate violence every day, violence deeply rooted in this highly militarized Lebanese sense of masculinity which requires a constant reassertion of the “Other” through subjugation, alienation, and exile. We hate the Syrians because they did what we could not do, and they paid for it with their lives. And this worked well for us. It is a convenient reminder of what happens when a people finds the will to look at its own life and be responsible for it.

We hate Palestinians for that reason too, but we hate them even more because they lost on our land. Palestinians are a permanent reminder of what can happen to us if we fail to do what we dare not to and yet know we must. The same goes for Syrians. We are not able to wish them away. They lost but we didn’t win. We gained nothing from their loss. Israel did, the Assad regime did, but we didn’t. And if we didn’t win, doesn’t this mean we lost too? We banish that question before it can be asked, for we are inflicted by a deep malaise that also shields us from having to face it. It is, as Samir Kassir wrote, a deeply Arab malaise, and a deeply Lebanese one as well.

To quote the poet Nadia Tueni: “I belong to a country that commits suicide every day while it is being assassinated.”