By the time Huda was arrested by regime soldiers in 2013, the siege of Daraya, a suburb of Damascus, was entering its first year. Huda was arrested with two of her friends at a checkpoint and taken to a prison in Muadamiya, a town just south of the capital. This experience shaped her worldview, Huda told the Syrian media outlet Enab Baladi: “After being arrested I knew the meaning of injustice and I am more willing to ask for freedom.” Huda, like many other Syrians, reported feeling a sense of awakening upon witnessing the brutality of the Assad regime first-hand.

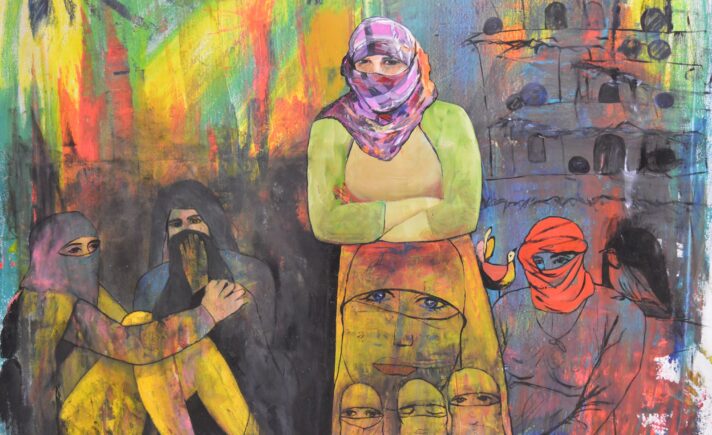

Fast-forward to August 2016. Daraya’s remaining people were forcibly evacuated after a deal was reached with the Assad regime to end the siege and return the town to regime control. They would follow the fate of the people of Homs before them and Aleppo and Eastern Ghouta after them. As the town was falling, a group of women from Daraya wrote an open letter stating: “We are demanding action from the international community” to prevent their forced displacement. No such action came, and so, Daraya fell.

Four years of siege by Assad’s forces and the Lebanese sectarian militia Hezbollah left this small suburb desperate for an escape. They knew what the regime had done to other liberated cities, a regime whose slogans of “Assad or we burn the country” and “kneel or starve” were applied with barrel bombs, sieges, and gulags. People gathered at the graves of loved ones, many of whom were killed during the siege, packed whatever they could, and left. Many of Daraya’s sons and daughters made it to Idlib, the city and area in the north of Syria where many refugees ended up. Of the approximately three million civilians currently in Idlib, around half are refugees from elsewhere in Syria.

Upon arriving in Idlib, Mohamed Abou Faris was told that he came from a special place. When he went looking for a job, a brick factory owner told him “you’re from Daraya, sir. You have everything. You’re our teachers.” Even before 2011, Daraya had gained a reputation for its nonviolent resistance to the Assad regime. Razan Zaitouneh, the celebrated lawyer and activist kidnapped by the rebel group Jaysh al-Islam in 2013, called the city “a star before the revolution and a star during.”

Decades of activism

This star shone in 1998 when, under Hafez al-Assad’s reign, some twenty youths were kicked out of a mosque by the cleric as their “lively discussions had veered too close to social change.” Among them was a then-18-year-old Yahya Sharbaji, who would lead non-violent protests again when Daraya’s time came thirteen years later in 2011. Their actions were inspired by a form of Islamic humanism influenced by the pacifist cleric Abdul Akram al-Saqqa, who in turn introduced them to the philosophy of Shaikh Jawdat Said, another influential advocate of non-violence. Their expulsion from the mosque may have been surprising for such young minds, but that didn’t stop them from continuing to question established dogma.

It shone again in 2003, when the US and UK invaded Iraq to depose Saddam Hussein. Daraya’s youth, including al-Saqqa’s son-in-law Haytham al-Hamwi, held a protest to stand in solidarity with the Iraqi people. The Assad regime, although officially opposed to the invasion, rounded the activists up and sentenced most of them to three to four years in prison. With the intense socio-political discussions generated by the ‘Damascus Spring’ intellectual revolt of 2000-2001, and with the fear that he would be next, Assad could not tolerate a resurgence of civic activity. At the same time, the Assad regime made itself available to torture ‘suspects of terrorism’ on behalf of the US government. This was made most notorious with the case of Canadian-Syrian Maher Arar, who was kidnapped by US authorities in 2002, sent to Jordan and then transferred to Syria to be tortured for eight months. To quote ex-CIA agent Robert Baer: “If you want people to be well interrogated, you send them to Jordan. If you want people to be disappeared, you send them to Egypt. And if you want people to be tortured, you send them to Syria.”

Daraya’s young men and women were of the generation that watched Bashar inherit the throne in 2000 and perhaps believed, as many did, that he would be different from his ruthless father. Bashar had even opened up space for activism and journalism, albeit within strict boundaries. He didn’t appear like his father who had built a reputation for crushing all dissent, controlling neighboring Lebanon’s affairs and suppressing the Palestinian/Leftist/Nationalist coalition of the mid-1970s. He didn’t seem like his uncle Rifaat, Syria’s ‘Butcher of Hama’ who crushed a Muslim Brotherhood uprising in 1982 by slaughtering up to 40,000 people, mostly civilians. He wasn’t like his brother Maher, the commander of the Republican Guard and the army’s elite Fourth Armored Division, who had built a notorious reputation for his savagery. Nor was he like his other brother Bassel, who was Soviet-trained and handpicked by Hafez to be his successor before dying in a car crash in 1994. With such relatives around Bashar, no one could have been prepared for this mild-mannered ophthalmologist, married to a ‘respectable’ British-born businesswoman who spent her time championing charities for Syria’s many social issues (with the exception, naturally, of freedom of speech). Everyone believed that Bashar inherited the throne with significant reluctance.

But reluctant or not, Bashar outdid them all. Within a year of the revolution, he besieged Daraya and restricted all movement outside the city, and even significantly restricted it within. The regime’s daily barrel bombs and snipers positioned on the outskirts created a city where no man, woman, or child would dare roam freely. It even went on a three-day killing spree, killing over 400, in August of 2012. The town was almost emptied: the pre-war population of around 300,000 was reduced to around 6,000 within a year or so.

An extraordinary experiment

To understand why Daraya became the first town in Damascus to be placed under such a tight siege, we should look at the extraordinary experiment in direct democracy that was born there. In a country where the army and its shabbiha, or sectarian thugs, served the interest of the few in and around the Assad family, Daraya’s Free Syrian Army rebels were under the authority of the Local Council. They embodied a model of governance that was antithetical to such a regime.

Abandoned by state services, Daraya resorted to self-governance and defiance, out of both necessity and conviction. As the British-Syrian writer Leila Al-Shami wrote in her eulogy to this rebellious city, the Local Council grew beans, spinach, and wheat. A relief office held a soup kitchen. A medical office oversaw the field hospital under impossible circumstances. In the early days of the revolution, Daraya’s revolutionaries even confronted the army sent to shoot at them with chants of “the army and the people are one.” Supported by the sound of church bells, these revolutionaries gained their image of peaceful protestors by handing out flowers and bottles of water to soldiers. They chanted for democracy and for equality for all of Syria’s religious communities and ethnic groups.

This experiment couldn’t survive in Damascus unless the regime ruling over this ancient city were to fall. And they knew that. This is why Local Coordination Committees were formed to coordinate protests across Syria. They were the brainchild of, among others, one of Daraya’s sons, a 26-year-old tailor named Ghiyath Matar. They were also the product of the Syrian anarchist thinker Omar Aziz’s conviction that the revolution could only succeed if it self-organized in ways antithetical to the regime’s authoritarianism.

In this city, a group of 40 young Syrian men between the ages of 21 and 30 even built an underground library. It had over 15,000 books collected from beneath the rubble of homes and from homes that would soon become rubble. They ranged from Islamic theology to Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist and Stephen Covery’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. The library housed a children’s section, and women who couldn’t leave their homes sent their husbands to pick up books from it. The young men even asked the books’ owners for permission whenever possible, and made sure to write their names in the books out of respect. In We Crossed A Bridge and It Trembled, Wendy Pearlman’s collection of Syrian testimonies, Wael, now a refugee in Sweden, spoke of how he thought of Daraya the first time he checked out a book in his new town: “A library means people will read, which means they’ll think, which means they’ll know their rights.” By the time the siege ended, the library’s fate joined that of Daraya’s people.

Ghiyath Matar was arrested on September 6th, 2011 and his mutilated corpse returned to his family days later. He was one of the first to go. In August 2018, the regime updated its records to list people who had died under torture in detention. The list included around 1,000 people from Daraya, including the Sharbaji brothers. Yahya and his brother Mohammed, known as Ma’an, were arrested with Ghiyath. Yahya was declared dead on January 15th 2013, Ma’an on December 13th of that same year.

They followed the fate of many Syrians who lost their lives in regime detention. In the notorious Saydnaya prison near Damascus, up to 13,000 people were hanged between 2011 and 2015 (and it is still operational). Omar Aziz died under torture in prison on February 17th, 2013. The Palestinian-Syrian open software developer Bassel Khartabil Safadi was executed in October 2015 in Adra prison, and his wife Noura only found out two years later. In Aleppo’s final weeks, the brutal four-year-long siege turned into another surrender. The de-facto capital of the revolution fell and the brutality of the town’s reconquest drew comparison with Guernica and Sarajevo.

I cannot list all of the dead, the ‘disappeared,’ the exiled. There are too many.

An idea called Daraya

This is the story of an idea called Daraya. Its people exposed the hypocrisy of a world that could let such atrocities happen, and only reluctantly welcomed a few survivors while leaving the rest to die. By doing so, the world exposed itself as criminal, through its inaction to protect the people of Daraya, Homs, Aleppo, Daraa, and Eastern Ghouta. This is a testimony to an inconvenient fact: that long before Syrians turned into refugees and were being scapegoated on the shores of Fortress Europe, the revolution they were building under barrel bombs, snipers, and sieges had already been abandoned to its fate. The Local Council’s many appeals to the United Nations, including in the final months of its existence, went unanswered. As the council correctly noted in January 2016, UN Security Council Resolution No. 2165 of July 14, 2014, “authorizes the delivery of humanitarian aid without requiring approval” from the regime. No satisfying answer was ever provided for why that humanitarian aid never came, why people were left to die from starvation or their inability to access medical treatment. No answer was ever needed for a crime so open for everyone to see in the age where massacres are live-streamed on Facebook and Twitter.

In the subsequent years since Huda was first arrested, the West’s self-declared gatekeepers of democracy watched actually existing democratic experiments die one after the other in Syria. And rather than speak of a European Crisis, the one that has so far allowed over 15,000 people to drown to death on its shores between 2014 and 2018 alone, we speak of a “migrant crisis.” To quote the everlasting James Baldwin, “what you say about somebody else reveals you.” The burden of proof has been thrown on the victims, on their mysterious ways, their darker skin, their cultural differences. In classical colonial arrogance in supposedly post-colonial times, the real crisis was avoided and, instead, the convenient scapegoats of the continent’s own structural crises were made to carry the cross.

Two weeks after Daraya fell, Bashar al-Assad went to the emptied town to pray in a mosque. Alongside him were high-ranking officials, including Mufti Ahmad Badreddin Hassoun, known locally as the Mufti of Barrel Bombs for his sermons advocating the violent crushing of protesters. The Mufti was also named in an Amnesty International report as one of three officials deputized to approve the hanging of people in Saydnaya. The message was clear, again. Assad or we burn the country. Kneel or starve. They rejected Assad, so Daraya was burned. They refused to kneel, so Daraya was starved. Assad’s message was also addressed to the world: “Look what I can do to them.” He also wanted to tell his supporters that they can live a ‘normal’ life under his rule, as long as they behave. As the Syrian writer Omar Kaddour wrote: “As the regime applies its scorched earth policy and starves the population to bring it to heel, it insists on showing that in the regions it controls, life follows its natural course.” Those living under its control in Damascus could live a relatively ‘normal’ life. It’s why refugees tended to flee to regime-controlled areas a number of times. They knew that the regime’s barrel bombs wouldn’t fall from regime-controlled skies.

This is the story of an idea called Daraya. It is the story of a sick world, a world with a sickness that, in the words of the Syrian writer and former prisoner Yassin al-Haj Saleh, “is aggravating our sicknesses, both inherited and acquired.” As more countries turn to increasingly authoritarian and xenophobic politics, those that were portrayed, against their will, as catalysts of that turn were made witnesses of the societies that produced it. As witnesses, they were forced to look at both Syria and the so-called ‘international community’ while being stripped of their agency to do anything about either. As for that community, it can exert its agency on Syrians and other marginalized groups without ever having to look at them.

Assad or we burn the country. Kneel or starve.