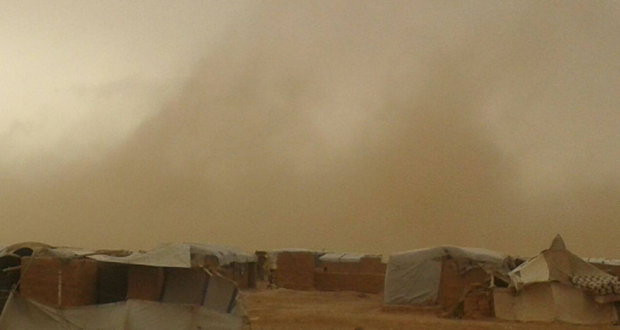

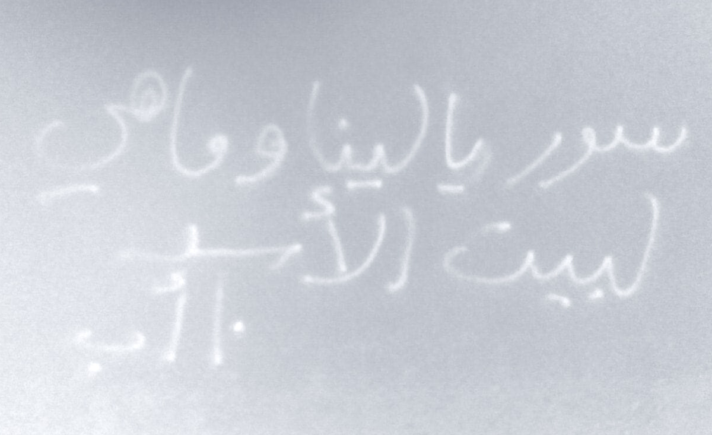

The recent videos coming out of the Rukban camp for internally displaced Syrians at the extreme northeastern tip of the Jordanian-Syrian border send shivers down the spine. Past days have seen torrential rain and hailstorms flooding the bare passages between worn-out tents and mud-brick huts; gale-strength sandstorms turning the air into a reddish-yellow soup, toying with the tattered rags of tents, tossing the rubble of makeshift walls as they please; and people in clothes made filthy with muck and sand trying in vain to repair what they can, imploring the world to help them or remove them from this frightening place in which they’ve become trapped.

The existence of such a camp in such circumstances as these isn’t difficult to comprehend for the general Syrian populace, who have grown accustomed to horrors they wouldn’t have imagined possible only a few years ago. Equally, it doesn’t appear that anyone in the world feels astonished or shocked by these scenes, after the inundation of death and pain that has gushed forth in the news and on social media without interruption for years. Yet a few minutes’ calm reflection on the particular catastrophe of Rukban camp ought to suffice to drive even a jaded soul to astonishment.

This camp, after all, is not in an area inaccessible for geographic or climatic reasons. Nor is it a concentration camp or collective punishment site held by some heavily-armed entity. Nor is it deep in the Syrian interior, encircled by a faction hostile to its residents, subjecting it to a siege that could only be broken by military means.

The Rukban camp, on the Syrian-Jordanian border, lies in an entirely internationalized area, around which almost all the states of the world come and go as they please. Jordan, and behind it the Gulf Arab states, are perfectly capable of getting humanitarian aid into it without obstacles. It sits in an area protected by a broad international coalition comprising dozens of states, including three permanent members of the UN Security Council, located just 25km from the al-Tanf base housing the same coalition’s forces as well as Syrian opposition fighters.

The Bashar al-Assad regime and its allies have severed the roads crossing the desert toward the camp, leaving its residents only a few weeks from disaster, some of their children having already died from lack of healthcare, then facing storms without anyone offering a helping hand, as though all the world’s nations were incapable of securing them food, medicine, and other basic humanitarian aid, at the same time as they have no difficulty getting officers, fighters, materiel, ammunition, and indeed food rations, to the very same area.

The Americans and Russians accuse one another of responsibility for the terrible humanitarian situation, while both could reduce its severity without the slightest difficulty. The Security Council goes on with its work, its meetings and discussions, and regional and international states continue their arguments about the constitutional committee, the dispute around which impedes the possibility of ending the tragedies faced by Syrians, including in Rukban, as though to secure food, medicine, water, and new tents and pre-fabricated houses required a constitutional declaration, rather than a small amount of money and a few cars and employees. There can be no doubt that the cost of improving the situation of Rukban’s residents would be less than that of another round of talks in Geneva, Astana, or Sochi.

Assad and his allies propose only one way to end the camp’s woes, which is for them to regain control over the area it sits in, and for its residents to return to their towns, cities, and villages through so-called “reconciliation” agreements, which is to say surrender agreements placing the fates of those residents at the mercy of the regime and its security agencies. To this end, the latter take the route of siege and collective punishment in broad daylight, by preventing the arrival of trucks and supply lines from areas under their control, while their UN representative Bashar al-Jaafari claims it’s Washington that obstructs the arrival of UN aid convoys by failing to secure the road leading to the camp.

For its part, neither Washington nor the coalition it leads does anything to secure alternatives to the aid that doesn’t arrive. Nor does Jordan permit the passage of convoys through its own territory, under the pretext of threats posed by the camp to Jordan’s security, with officials constantly recalling the Islamic State (ISIS) attack that took the lives of six of its border guards near the camp in 2016, as though to punish the camp’s residents for the attack, ignoring the fact that ISIS also attacked the camp itself several times, deeming its residents agents of the international coalition.

The picture, in summary, is that Russia, the Assad regime, and Iran use the camp as a card with which to press for the coalition’s withdrawal from al-Tanf and its environs; and that the international coalition has little interest in this Rukban card, but perhaps prefers that its burden be lightened; and that Jordan wants its Syrian borders to return in their entirety to the regime’s hands, in order for security and intelligence cooperation to become easier, even if that necessitates the loss of tens of thousands of Syrian lives; and that ISIS continues to benefit from all the mutual antagonisms to maintain its presence in parts of the desert; and that the UN cannot save a single child from death if “sovereign” states do not agree to save it.

The case, then, is complicated, and it’s this complication that drives civilians in Rukban to their current fate. It’s the same complication that has led to the destruction of Syria, and the rending of the lives of its people; the complication arising from placing state sovereignty above the value of human lives. State sovereignty is the foundational principle of the UN Charter. The scenes coming from Rukban serve as sound evidence of the inhumanity of this principle, and the moral baseness of those safeguarding it.

[Editor’s note: This article was originally published in Arabic on 31 October, 2018]