[Editor’s note: This article was originally published in Arabic on 28 May, 2018]

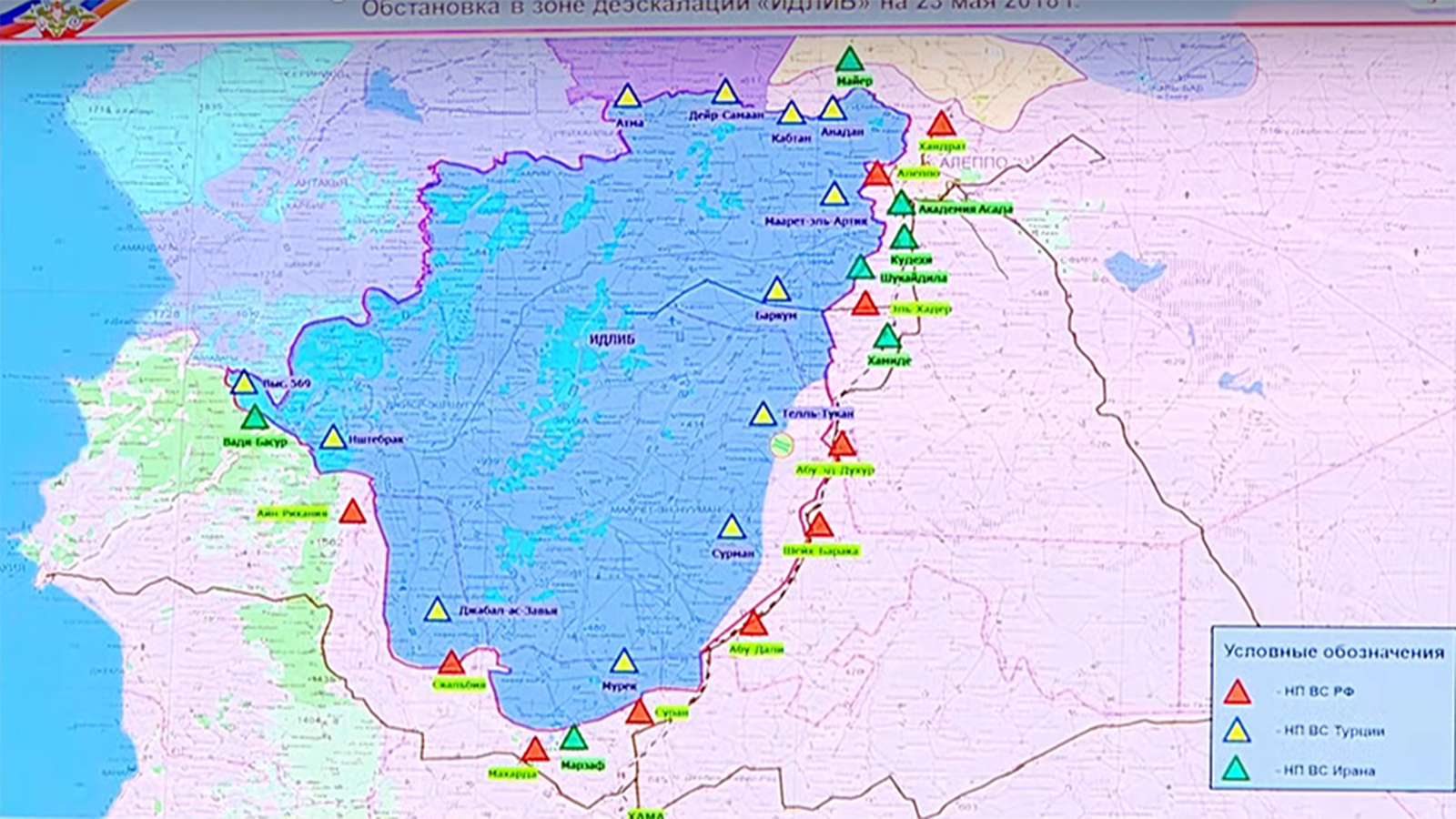

Last Wednesday, the Russian defense ministry announced the finalization of the stationing of military “observation posts“ around the outside of northern Syria’s Idlib Province, in accordance with understandings reached during negotiations in the Kazakhstani capital of Astana, where it was agreed to erect seven Iranian posts and ten Russian ones within the territory held by the Bashar al-Assad regime, and twelve Turkish posts in the areas controlled by opposition factions.

Officially, the purpose of these posts is to monitor any violations committed by any party of the so-called “de-escalation” agreement, and to issue a joint statement in that regard, to be circulated periodically by the Russian defense ministry on its website and social media accounts.

In practice, however, the likely key function of these posts is to firm up the shape of the map of control in Idlib, and to form a deterrent against military escalation in the region. That’s to say, they aim at more than just implementing the “de-escalation” memorandum in Idlib—to which Russia has anyway not adhered in other areas, such as Eastern Ghouta and Northern Homs Province. They appear, rather, to be a sketch of the zones of influence pertaining to the three states sponsoring the Astana process (Russia, Iran, and Turkey).

“Influence” in this context derives from guaranteeing commercial traffic in Syria, in a manner consistent with the country regaining its role as a center of land transit trade toward the south (with Jordan and the Gulf states). For the talk today doesn’t end at placing observation posts near the frontlines, but extends to securing the Aleppo-Hama highway, which is part of the international road stretching from Turkey to Jordan.

This development, which works in Turkey’s economic interest by facilitating commercial traffic toward the Gulf and the MENA region generally, will also achieve one of Moscow’s fundamental objectives, namely the appearance of a partial return of economic vitality in Syria. This will help the public relations campaign led by Moscow regarding its role in the country, and also reconnect neighboring states with economic interests they won’t wish to cut anew, especially in the case of Jordan, which is pressing the opposition factions of southern Syria to re-open the Naseeb border crossing and hand it over to the Assad regime, in order to recover what is for Amman a vital commercial artery.

The question of restoring life to the international roads in Syria is a vital one from Moscow’s strategic perspective. At a time when the latter’s military victory, after the massacres it committed in Eastern Ghouta, has enabled it to secure the Damascus-Homs highway; and the population displacement it enforced in Northern Homs Province gave it control of the Homs-Hama highway; agreement with Turkey on distributing observation posts to secure the Aleppo-Hama highway would be the penultimate step in securing the principal international road in Syria, which extends from the Turkish border north of Aleppo down to the Jordanian border in Daraa Province. It may be worth adding here that recent media leaks speak of a Russian-Turkish agreement to render the international Aleppo-Gaziantep highway operational once again.

A scenario such as this would have numerous key consequences. The securing of the roads between Aleppo and Hama would mean that the strategic weight south of Aleppo, parts of which region are controlled by Iranian-backed militias, would diminish in military and economic terms. Likewise, the re-opening of the international roads would facilitate the reconnection of Syria’s provinces with the central economic cycle in Damascus—which is run first and foremost by businessmen and influencers linked organically to the Assad regime—and would strengthen the domination of Turkish products over the Syrian market, after the loss of the majority of the country’s industrial infrastructure.

Alongside the economic effects, the confirmation of such understandings as these would mean that the path had been paved for confirming the more important understandings in Syria between the three Astana states to obtain the legitimacy to divide up influence within a political agreement sponsored by those states. The pressures currently faced by Tehran would appear highly favorable for the implementation of such an agreement, which Iran has long opposed in the hope of obtaining the largest share of control as a result of its militias’ direct support of regime forces on the ground since the start of the Syrian revolution.

From Turkey to Jordan, and from Tehran to the Mediterranean, it seems that all the region’s roads pass through Syria, albeit that their paving was only made possible by the destruction of the country, and at the expense of the blood and suffering and agony of millions of Syrians. If the regime in Damascus appears, by virtue of these understandings, to be in a secure position, that is less the result of the “victories” attained by Russian fighter jets than of its acknowledgment that it is the weakest link in the chain of the “victors,” and its consenting to hand over the country for the drawing of maps of regional and international control and influence, in exchange for Assad’s remaining on the seat of nominal power.