The sun gathers its rays and recedes, carrying its light elsewhere and leaving it to electricity generators to dispel the darkness of the city. I hasten my steps as the roar of generators reverberates in my nerves. I finally arrive at my grandfather’s house, which is located at the center of our town, which is in turn located midway between Homs and Damascus, towering among the rugged rocks of the Qalamun Mountains. No one is there except my grandmother. She sits on a sofa near the fireplace which renders the room resemblant of a furnace or a sauna. “Oh… Who is it?” she asks in her usual bewilderment.

We sit across from each other. I am sweating; Grandma is shivering. She adds more fuel to the fireplace, which compensates in warmth for all the cold years of her life, or so they say. I stare at her glowing face, with the light of the fire reflecting on it and bestowing a gracious aura upon its features.

No one knows exactly when she was born, herself included. Her sister passed away just before she was born, and she was named after her, and inherited her ID card later on. Our grandmother in the ID is her sister in the grave. We suspect that she is nearing eighty years of age. And yet, her skin still resembles that of a young girl, as she has long anointed it with rosewater and massaged it with lemon and cucumber peel.

Grandma rolls up her sleeves to perform wuḍū’ (partial ablution), lamenting Umm Ahmad, who seems to have punctuated her arrival to Grandma’s wuḍu’, and Umm Ismail who never ceased to knock the door while Grandma was praying. I look at my watch, embarrassed, then I remember that even official speeches and coups d’états, as well as power outages, all conspire to adjust their schedules to the timing of Grandma’s wuḍu’ and prayer.

With a simple calculation to divide the day between her ablutions and prayers, the remainder is but a few minutes escaping the stretches of time she had dedicated to these two acts. Only a fortunate few get the chance to coincide these fleeting periods of times. This is because Grandma prays along with every farḍ (compulsory prayer) another one, in an attempt at atone for those she had missed before she was guided back to Islam. This happened in the late 1980s, after a student of Al-Fatih Islamic Institute had proposed to her granddaughter.

Then arrives the adhān. Ten minarets in this small town call for prayer simultaneously.

“Thank God for the grace of Islam, and what sufficient blessing it is,” she mutters. She then prays for her seven children, then the grandchildren scattered across Germany, Turkey, Gulf countries and the Homeland. They are many, but only one daughter and a few grandchildren have remained in Syria. We have our usual quick and disjointed conversations. I ask her about her favorite subject: her method of housekeeping. I never tell her the news about her two granddaughters who have taken off the hijab in some cold and faraway countries.

Before the Family Found God

As is the case with most Qalmouni families, religion did not have paramount status in my grandfather’s household in the 1960s and 1970s. The hijab, for example, was more of a prevailing social norm. In addition to embroidered dresses, women covered their heads with headscarves that often revealed their necks and some of their hair, just as men dressed in kufiya and headband. In fact, modest clothing has been rather a rural custom of virtually all villagers.

Religiosity began spreading mildly in the early 1980s, and was in our family limited to individual and moderate devoutness expressed by the eldest son and a son-in-law. In the late 1980s, however, the eldest granddaughter began wearing the hijab. She was influenced by the young religious uncle, who used to pass to her prohibited cassettes of Islamist singer Munther Sarmini (known as AbulJoud); as well as by her teacher, sheikh Adib Kallas, who had been sent to the village as a teacher of religion in the girls’ public high school. Kallas was one of the most prominent sheikhs in Damascus, and he had been schooled by sheikh AbulYusr Abdeen

Administratively speaking, Qalamun villages belongs to the Rif Damascus governorate, which is all under the intellectual, religious and political influence of the capital city. Knowing what is happening in Damascus is a prerequisite for understanding the Rif (countryside). In his early reign, Assad’s relationship with Damascene religious groups was pretty tense. His opponents often highlighted his religious and sectarian heritage to challenge the legitimacy of his rule. Hafez al-Assad was both in need of and at war with Islamism.

In the 1980s, a violent confrontation broke out between the Muslim Brotherhood militants and the regime, in which Assad crushed all militant Islamists and persecuted others with arrests and executions. Following horrendous massacres, however, he was quick to make concessions to the sectarian majority population. He gained the favor of some clerics by granting them more social influence, allowing them to preach and disseminate their teachings as long as they remain strictly apolitical. He continued to hold sway after he reached a suitable formula for the relationship between his rule and religion.

The Syrian regime is secular in terms of general characteristic, or it claims to be so. Yet in exchange for fuller monopoly over politics and power, it has loosened its grip on “public religious practices” and allowed the Islamic character to overly imbue social life.

Thus, a symbiotic relationship emerged between the regime and a group of religious scholars and clerics, in which the latter managed to restore legitimacy to the status quo in exchange for formal concessions and privileges. It was something of a bargain for the benefit of both parties. Assad induced sheikhs he had selected, such as Ahmed Kuftaro, who later inaugurated the vast Kuftaro Foundation (known colloquially as AbulNour complex); Saleh Farfour, who founded Al-Fatih Islamic Institute, and Muhammad Said Ramadan Al-Bouti, who antagonized Islamism and whoever aspires to exercise politics among Islamists.

Al-Bouti’s approach has been disengagement from politics, retaining their exclusivity to the “sultan.” As he puts it, “Preachers who call to God and introduce His religion must turn away from rule and rulers; so as not to tarnish their Islamic identities with political goals and thus lose people’s faith in them. If goodness wins out and commitment to Allah’s religion in society prevails, rule would automatically be imbued with Islam and its regime”

A Granddaughter’s Hijab Ceremony

The eldest granddaughter was the first girl to wear the standard Islamic veil in the family, amid fears and reservations voiced by many, especially with incidents of unveiling women by Rifaat Assad’s Defense Companies in 1981 lingering in their minds. Her consent to marrying a student at Al-Fatih Institute

In addition to the genuine Islamic thought he bore, the young fiancé had such Damascene amiability. He engulfed the family with his geniality and frequent visits, until the the family’s Qalamouni spirit grew more tender and accepting of him. After a few months of preaching, girls in the family began to wear hijab, commitment to prayer began to prevail, and regular religious lessons began to be held for children and adults, men and women alike. Despite the grandfather’s reservations, the family was exceedingly welcoming to him, and its fears gradually receded.

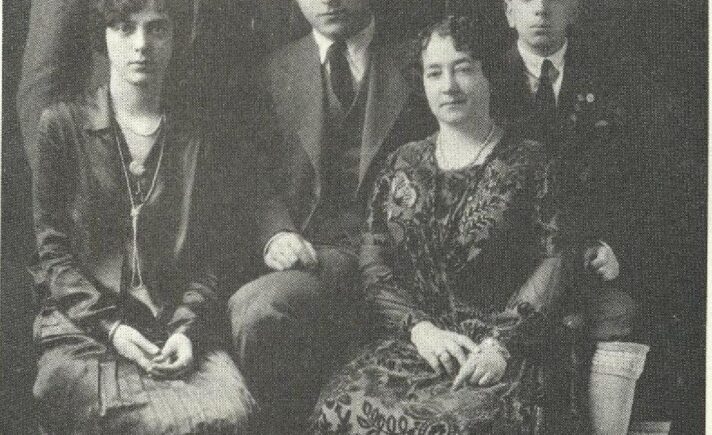

My Grandfather

Our grandfather was not religious, and he was not promptly attracted to the faith. We learned through the grapevine that he consumed alcohol, and that he happened to return home intoxicated. He was nonetheless very noble and straight, and extremely venerable. He never slept a night owing someone a nickel. He used to be an officer in the Syrian Army, which highly appreciated his services and asked him to join the reserves several times. He was a patriotic person of the highest caliber. Bitterly disappointed in the scale of corruption, he withdrew from the army, feigning pain in his back. He moved on to other forms of services, investing in a private school at first, before settling to cultivating his land in the village.

We do not know much about Grandpa. He was reticent. His story was inseparable from the history of Syria and its taboos. Only after the revolution have I learned that they found among his belongings a medal of honor from the military, which could enable him to enroll all his children at any university of their choice. But he refused to use it, saying in unyielding determination “I want nothing from them, my son studied engineering with his own grades.” It was inexplicably defiant of him.

I also learnt that he fought with the Army on the frontlines against Israel in 1967, before soldiers were ordered to vacate their stations, leave their arsenal behind and retreat. He refused. He took with him in a tractor-trailer whatever soldiers, weapons, ammunition and gears he could, and returned to the battles. He was later punished for disobeying orders.

Grandpa was not pliable or easily pressured. His psychological fabric seems to have been kneaded from the Qalamoun soil itself; tough and solid. We have been told that our compassionate grandfather is someone different from the strict father who raised his children. If he were among us today, I wonder, would he side with the revolution, driven by his hatred of the regime? Or would he oppose it, driven by his knowledge of the regime and what it’s capable of doing?

The Nineties

Faith and religious practices gradually proliferated within the family, despite their contradiction with the nature of the locality and and what its people had been familiar with: gender-mixing, alcohol, nightly celebrations and simplicity. However, adamant Qalamouni stones were destined to yield to mellow Damascene water, and people were eager to whatever gives them meaning and answers their profound questions. Any means of consoling their scarred conscience was welcome. The defeat in 1973 and the loss of the Golan Heights in 1967 were too calamitous to bear. How would the Israeli occupation triumph over our patriotic songs, progressive regimes and the entire Arab states combined? A popularized notion at the time suggested that the reason for these defeats is being led astray from God’s laws; for Allah shall not bestow His victory onto those who do not uphold His religion. Combined with a lately loosened security grip which had strangled Islamists, this notion contributed to pushing people towards more religious lifestyles.

In the 1990s, religiosity witnessed a remarkable surge under the watchful eye of the state. The regime allowed the return of some of the sheikhs it had exiled after the 1980s, including Abd al-Fattah Abu Ghudda and the two sons of Abdul-Karim al-Rifai, the founders of Zayd Group in Damascus. This return was facilitated by other sheikhs close to the regime. Shami (or Levantine) religiosity, which is sometimes referred to as neo-orthodoxy, began to adhere to the political line; outwitting the political class at times, and being overpowered by it at others. Islamist movement managed to devise their own epistemological tools, reproducing themselves, expanding their networks and re-establishing their spheres of social and political influence. Religiosity penetrated the depth of society vertically, and expanded and proliferated horizontally. Mosques became saturated with preachings and teachings, students at sharia institutes increased in number, and religious lessons reached homes. In the meanwhile, strong economic ties were being established, notably with the Damascene business community which was a pure asset for “social Islamism.” This coincided with the use of technology, wherein religious tapes, books and graphic novels spread like wildfire. The vines of religion grew and intertwined with the fences of politics.

Subsequently, it was only natural that turning to religion in the second generation, i.e. Grandpa’s sons and daughters, would automatically enact change in the second generation of grandchildren, who inherited devout faith from their parents. The upbringing was based on unquestioned obedience, and everyone thus complied with the new emerging lifestyle. It was clear what to do: obey orders. Only one girl rebelled against and refused to comply. “I do not want to cover my hair!” she exclaimed.

After the 1990s, a new generation in the family was indoctrinated at a tender age with religious notions and observances, exceeding their parents’ religious commitment, and growing up doomed to revolution later on.

The Death of the Father-Leader

On June, 10th 2000, Hafez al-Assad died. Sheikh al-Bouti led his requiem mass, so moved that he cried as he eulogized him. “What a hypocrite!” my grandfather commented.

We had known al-Bouti and seen him often on TV, but we hardly understood what he talked about. His nomenclature was too difficult for our comprehension. After the son’s rise to power following a sham constitutional amendment, al-Bouti religiously legitimized the bequeathing. Forty days after the father’s death, al-Bouti mocked the “artificially conceited democracy,” as opposed to “a pure, honest allegiance pledged by the people” to the new president Bashar al-Assad

Since then, Bashar al-Assad’s regime permitted other sheikhs to return to Syria, including Abdulqadir Habannakeh and Mustafa al-Bugha, while opening the door for Zayd Group to resume its activity under the leadership of al-Rifa’i brothers, Osama and Sariya. In the meanwhile, preacher Mohammed Rateb al-Nabulsi and scholar Wahbah al-Zuhayli rose to pan-Arab prominence. The hearts of Syrians were beginning to be caught by the hook of Islam, becoming evermore attached to it as ordeals and crises continued to befall the Arab world: The September 11 attacks, the US invasion of Iraq, the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, and the siege of Gaza.

We would watch TV and follow what was unfolding on each ordeal, then perform congregational prayer with sincere humility before God. The sheikhs maintained that if people were more God-fearing, so would be their regime, for authority is a divine instrument warranted by our sins: “Your leadership is a reflection of you,” as goes the traditional saying. They kept calling upon us to establish the state of Islam in our hearts, and then we would witness it materialize on the ground. Despite the successive crises, an optimistic sense overwhelmed our family, as well as Syrian society, that the both the State and Islam were heading towards a bright future under the leadership of the young President “Dr. Bashar.” I recall how we rejoiced when Assad stated in his speech “Syria is under Allah’s protection!” We believed that faith has entered the heart of our president, and that said State of Islam is forthcoming. Apparently we had completely taken in the Baathist bait.

In 2000, the girl who had rebelled against the hijab had two options: “Either you wear the hijab and get baccalaureate preparatory courses, or you get no courses during the summer.” The girl remained stubborn, abandoning the summer baccalaureate courses and preserving her liberty. A few months later, she wore a hijab alongside a group of her friends, who by then had been influenced by the rising star in religious TV, Egyptian preacher Amr Khaled.

The state was evidently in full support of “moderate” Islam –as we called it at the time– or –more precisely– “official” Islam. While the state denied all requests for the licensing of political forums during the short-lived Damascus Spring, it nonetheless approved the licensing of a forum aiming to disseminate “moderate Islamic thought” within only two months of the request

The Qubaysiat

The Qubaysiat were named after sheikha Munira al-Qubaysi, a disciple of the late Grand Mufti Kuftaro. As of 2003, the regime officially allowed them to operate. Sheikh al-Bouti had been rumored to say “They continuously pray for President Bashar al-Assad without any engagement in politics; their loyalty to the President is absolutely unblemished.” Having been working in hiding since the 1980s, they have intensively permeated Syrian society, before beginning to spread across other Arab and even Western countries.

The Qubaysiat mostly work as teachers in schools and institutes. Around 2013, a Qubaysi Miss used to visit us to supervise our memorization of Quran and tell us tales of prophets. After their official license, they took over all the Assad Institutes and monopolized religious education for girls.

Almost all of the girls in my family attended their lessons and memorized parts of the Quran under their supervision. Notably, it should be noted, religious education was not about abstract sermons; it was rather a holistic social and cultural cultivation, combined with all sorts of entertainment activities, continuous encouragement, celebrations at the end of each summer or winter semester, in addition to honoring the achievers with trips to perform pilgrimage.

Our town had no theater, cinema, café, or conservatory. Thus children spent summers between computer classes, language courses and Assad Institutes, before heading back to schools in the winter.

A Workshop for Islamic Garments

Up until 2003, the manifestations of religiosity had been limited to a handful of families in our village. Among the major difficulties faced by the nascent born-again-Muslim community was finding suitable clothing for their veiled daughters, ones that are spacious, yet modern and stylish. The market had not evolved to meet such requirements back then. Members of my family came up with the idea of establishing a small workshop for the design, and later sale, of Islamic garments.

The idea was received with great enthusiasm. Given to the difficulty of finding skilled tailors and dressmakers, however, it was not destined to be more than a mere idea.

In the meanwhile, mosques were being extravagantly constructed in our village, which was being transformed into a town, with its economic conditions improving due to remittances flowing from young expatriates in the Gulf.

With Amr Khaled TV shows as the trendy face of Islamic preaching, in addition to the efforts of the sheikhs and sheikhas in Syria, religiosity increasingly ceased to be an individual or family phenomenon and became the social norm. The hijab with the manteau (long coat for chaste women) prevailed, and religious individuals became a majority which either attracted the rest, or exercised a type of collective symbolic power that happened to be harsher than the state’s naked power.

Freedom: The Stick Cracking the Ice

As the revolution sparked in Daraa, and protests broke out in the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, debates raged all over the family. A state of rebellion and terrible tension overwhelmed the spirits. The string was strained to its maximum capacity, and we heard our hearts being torn apart. The youngsters, as usual, waited for the religious elites to take action before following suit.

To their surprise, the family’s sheikh stood against the revolution. Our family was for the first time divided in half, along the lines of support or opposition to the revolution, i.e. with and against the family’s sheikh. Many were disappointed in the sheikh’s firm stance. As violent zeal began resonating within their chests, the young men and women passionately argued with their master for the first time. They even berated him for his pro-regime views, only to find out later that these were not his own views, but rather those of the religious establishment. Frustrations grew even more dire.

Discussions recurred, at times turning into verbal brawls. The young family members were not familiar enough with history to better understand what was happening. All they could discern was that the former alliance between Islamists and the regime had been only a temporary balance necessitated by the political juncture and regional considerations. Now that the people revolted, where are those elites?

Over time, it became evident that the regime had masterfully woven the precise role of Islamism, which in turn went according to plan. After long discussions and heated arguments, while horrific massacres were taking place, it became clear that the train shall not deviate from its decades-long habitual path. It was the people who left the train and took to the streets, protesting against Assad from the very mosques he had been appropriating. The institutions that were made to be strongholds of indoctrination turned into hotbeds for the uprising.

The family had been only ostensibly coherent, supposedly following one religious reference and adhering to the same political views. But the word “freedom” broke the static balance and split it in half. Other schisms followed, and divisions grew. The family began to look like a huge mirror that was shattered by an axe and turned into small pieces and fractures, a mosaic that harms whoever tries to touch it.

The Seed of Rebellion

Those who had been injecting religious knowledge in the veins of young people, filling their heads with aspirations of Renaissance, fled in panic as the first cry of freedom emanated into the ether. The momentous aspirations of the youth were rendered empty promises. Not a single word was uttered and lived up to the calamity of the situation. Religious leaders withdrew and shut themselves in, before conceiving of their anti-chaos doctrine, and ultimately siding with injustice. The near unanimous position of Syrian Muslim scholars was condemnation of the revolution, with a few exceptions that only confirmed the norm. It was utterly staggering.

The young men and women had to swallow the bitter pill and realize that religious and political establishments are intimate allies. They had to discover the extent to which religion was involved in politics, which made them skeptical of everything that arrived to them through the regime, including its official variety of Islam. They witnessed the regime’s shocking ability to lie and fabricate. Minds were set ablaze, and the seed of rebellion began to grow in their hearts.

The youths began to understand the stark difference between the religious establishment and true religious piety. They rallied around the sheikhs who have taken up the banner of freedom, despite their late arrival (Sariya Rifa’i, Krayyem Rajih, Moaz al-Khatib, as well as pro-revolutionary Islamic thinkers such as Ahmed Khairy al-Omari, Mamoun Deiranieh and AbdulKarim Bakkar). Internet access had already begun improving in the country; smartphones were within the reach of any hand; and the regime was too overwhelmed to control the flow of information as it had before.

As hearts bloomed and began to tear down preset boundaries, the revolution and concurrent massacres were putting tremendous pressure on everybody. Debates continued to rage. The family’s sheikh was armed with traditional statements and attitudes. Among those was the infamous fatwas of al-Hasan al-Basri, who stood against the qurra’s failed revolt. “What do you say about fighting this oppressor who has unlawfully spilt blood?” al-Basri was asked, to which he replied: “I hold that he should not be fought. If this is a punishment from Allah, then you will not be able to dispel it with your swords. If this is a trial from Allah, then be patient until Allah’s judgement comes to pass; for He is the fairest of judges.”

The family sheikh went on to quote prophetic words in regards to obedience to the rulers “even if they whip your backs and take your wealth,” in addition to stories that date back to the reign of the Umayyad caliphs and their tyrannical viceroy al-Hajjaj. Despite the fact that the Quran praises Moses and his revolt against the tyranny of Pharaoh, any discussion with clerics and religious authorities on these grounds would be rendered obsolete, since the ball would always be in their court.

While the revolution was such a legendary and fascinating event for the youngsters in our family, an historic moment that arrives only once in a lifetime, it was only viewed as a repeated farce by the sheikhs, who seemed to know the arguments of their young opponent a priori.

The chaos, the conspiracy and the country’s devastation were the only ready-made responses to the demands of freedom, dignity and equality. The sheikhs opted to preserve the gains and interests they had been keenly garnering from the regime, so they viewed what was happening as a plot aimed at cutting “their” religion’s lifeline. The youth in our family were frustrated by all the absurd arguments, while blood was being horrendously split all over the news. The elites fell from grace forever, and young people had to learn the harsh lesson that they must make their way on their own; to be their own vanguards and pioneers.

The young family members began building a fleet to sail through the sea of rhetoric, in search of less shameful principles. They began looking for rebellious and responsive religious authorities that are more in tune with their concerns, ignoring the pleas and warnings of the elites, and leaving behind all the sham achievements of scholars who were either too scared or in cahoots with dictatorship.

While what I have characterized in this article concerns the affairs of my grandfather’s family, it can be more or less generalizable. For we are but a small cell and random sample, which affects and is affected by what is happening to the whole body.