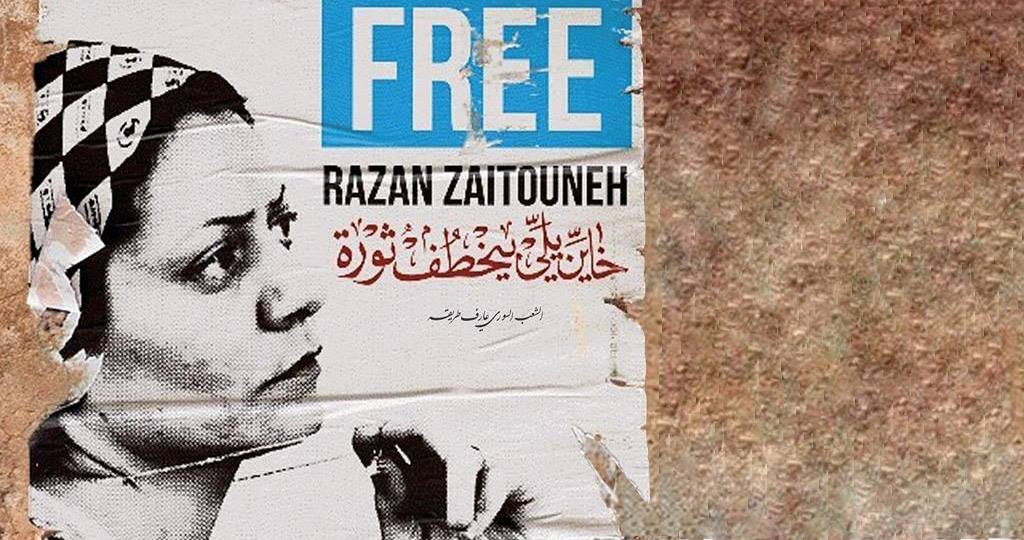

There was a time, not too long ago, when a young woman headed one of the largest networks of Syrian activists working against the Assad regime. She had blue eyes and uncovered blond hair; she spoke English and held a degree in law; and she was a staunch secularist. But Razan Zaitouneh was utterly uninterested in showcasing any of these ‘qualities’, or in becoming an international icon. She believed in the universality of freedom and human rights, but it was only through very local battles that she thought such values could acquire life and meaning.

It was in 2005 that I first heard of Razan. She had taken part in a small demonstration in Damascus, and soon thereafter stories circulated of her exceptional bravery. Razan Zaitouneh had raised chants against the Assad family when, for most Syrians, the mere mention of the president or his father was reason enough to shudder with fear. She had spoken the radical truth when older activists and most international observers were content with their vague demands for ‘reform’ or ‘gradual change’ in Syria.

And so when the Syrian countryside rose up in rebellion in 2011, Razan did not hesitate to join the struggle. With her husband Wael Hamadeh and many old and new friends, she had soon built a formidable constellation of ‘Local Coordination Committees’, which covered around fifty different locations in the country. The LCCs organized and documented demonstrations on film; they tracked the rising numbers of the dead, the wounded, and the missing; and they started to provide and coordinate humanitarian assistance to the displaced families. They also elected a political committee that debated all matters related to the Syrian uprising, and offered a detailed vision for a truly democratic and pluralistic post-Assad Syria.

It was all the stuff of true revolutions, and for those of us who took part or helped from outside, the experience was often truly euphoric. But by the time the uprising had entered its second year, the inclinations of the mostly secular and pacifist members of the LCCs seemed at odds with the grand political realities and ideological forces that were now at work in their country. The savage repression of the Assad regime had made it impossible for the people to continue with their non-violent protests. They started to carry arms, and with that, their need for an ideology of confrontation and martyrdom started to eclipse their earlier enthusiasm for forgiveness and reconciliation.

For many civilian activists, the transformation of the Syrian uprising into what seemed like a full-blown civil war was unbearable. Of those who escaped death or detention, many decided to flee the country; and, from the bitterness of their exile, they began to tell a story of loss and disillusionment. But for Razan, Wael, and many of their close friends, these same developments called for more, not less, engagement. They argued that civilian activists had the responsibility now to monitor the actions of the armed rebels, to resist their excesses, and to set up the institutions for good governance in the liberated parts of the country. They also believed, much like their friend the renowned writer Yassin al-Haj Saleh, that their task as secularists was not to preach ‘enlightenment’ from a safe distance, but to join the more ordinary and devout folk in their struggle for a life lived with dignity. Only then could liberal secularism earn its ‘place’ in Syrian society and truly challenge its primordialist detractors.

It was these beliefs that set Razan Zaitouneh on her last journey in late April 2013. After two years of living underground in Damascus, she followed the example of Yassin al-Haj Saleh and moved to the liberated town of Douma. There, among a starving population that was constantly under shelling by the regime forces, Razan launched a project for women empowerment and a community development center, all while continuing her work in documenting and assisting the victims of the war. By August, al-Haj Saleh had already left for the north, but his wife Samira al-Khalil, Razan and her husband, and their friend, the poet and activist Nazem Hammadi were all settled in Douma, sharing two apartments in the same building. In the middle of the night of December 9, they were abducted from their new homes by a group of armed men that were later linked to Al-Nusra front and the Army of Islam. To this day, their fate and whereabouts remain unknown.

Razan Zaitouneh did not cover her hair in Douma, nor did Samira al-Khalil. They did not ‘go native’ in the conservative town, because they believed that to be a native of Syria should not require conforming to any one cultural or political mold. This alone seems to have terrified the new Islamo-fascist forces in the area in the same way mass protests had terrified the Assad regime. But beyond these local actors, the presence of people like Razan Zaitouneh also disturbed the narrative that the world had found most convenient to adopt about Syria, in which true democrats were seen as weak or entirely absent in what was now only a sectarian civil war. If this statement has a ring of truth now, it is only because for two years the true democrats have been left to fight a brutal dictatorship, Al-Qaeda extremists, and corrupt warlords all by themselves. Already in December 2011, when Amy Goodman asked her what she expected from the world, Razan replied “I do not expect anything anymore”. She was right. The world has done nothing for Syrians like Razan. At least not yet.