The double standards of Western media coverage on Palestine and Israel will at this point be very familiar to critical readers. Years of regular Israeli aerial bombardments of Gaza and repression of Palestinians in the West Bank have established a particular framing: Palestinian “terrorists” as the initiators, Israeli “citizens” as the victims, and the people of Gaza as unfortunate, more so than regrettable, collateral damage. The bias is exemplified by the disparity in the language of reporting: Israelis are “killed”, while Palestinians “die.”

Importantly, this is not new – it is cumulative reinforcement. From a discourse analysis perspective, coverage of the ongoing “operation” in Gaza, the largest Israeli campaign of mass bombardment ever conducted, can be considered a continuation (or even, natural progression) of the tropes which have been established over a number of years. The traditional stalwarts of such narratives are the Israeli and US mainstream media: prominent figures in Israel have variously described Palestinians as “human animals”, “cockroaches”, including calls for Palestinian villages to be “erased”, vocabulary which comes to be represented in US and Israeli media coverage often with limited critique or contextual background.

UK media outlets are far from immune to influence and agenda, particularly those with a reputation for integrity: UK journalist and documentary director Harry Fear recently accused “Western media” of exhibiting bias in its coverage of the current conflict in Gaza, saying the “overarching storytelling” is based on an Israeli-directed narrative. There are various ways in which this can be measured: framing, language, and selection bias.

Framing, language, and selection bias

Framing concerns how particular UK outlets build a picture of the conflict, through narratives which obfuscate context and position the suffering of Palestinians and Israelis on very different hierarchies. Rather than situating the conflict in the context of 75 years of occupation and violence in Gaza and the West Bank, the Hamas attacks of 7 October were presented by most mainstream UK outlets as “unprecedented”, a “surprise attack” that “no one expected.” Current reporting and even broadcast discussions on the subject of the Israeli bombardment of Gaza continue to start the clock on 7 October, “in the wake of Hamas attacks”, despite years of successive large-scale Israeli military campaigns in the Palestinian territories. Positioning the storyline within such a limited timeline not only cultivates a collective amnesia amongst the UK media audience, for whom the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is assumed to be excessively complex, but importantly, it presents the current offensive as unilateral: Hamas struck, and Israel has a right to defend itself. The inference is that if Hamas hadn’t struck ‘first’, Israel would not now be compelled to issue a “final plea” for Palestinians to evacuate their homes. The suffering inflicted by Hamas operations in Israeli territory is deplorable, but the deaths of civilians, total devastation of infrastructure and livelihoods inflicted on Gazans are solely the result of the act of the initial aggressor. Some outlets even position Palestinians as collectively responsible: The Daily Telegraph, a conservative UK media outlet, recently released a comment piece titled, “There can be no peace so long as Palestinians want to annihilate Israel.”

On the other hand, the Israeli offensive on Gaza is subject to a device known as ‘military framing’, where facts from the ground are reported using terminologies related to military strategy. Whilst the events of 7 October are reported using epithets such as a “murderous rampage carried out by Hamas” and a “bloodthirsty attack”, descriptions of Israel’s relentless bombardments and invasion are couched within militaristic language: Israeli forces “fight through the night” to prepare to conduct a “ground offensive.” The BBC live-streamed the Israeli forces’ heaviest bombardment of Gaza on the night of 27 October. Due to the near-total electricity and communications blackout caused by the strikes, the videos were only illuminated in regular intervals by the light of explosions and resulting fire, so military commentators were offered alongside the footage to provide dense descriptions of the Israeli military strategies used to “neutralise” Hamas targets – although the total Palestinian death toll inflicted in the strikes is believed to be amongst the highest of the conflict so far. Other UK outlets offered complementary analysis of Israel’s alleged targets, Hamas’ “vast labyrinth” and the “spider’s web of tunnels.” Framing Israel’s offensive within such structures as military terminology effectively sanitises and legitimises their activity, and neglects the very real human cost of these actions. Meanwhile, due to Israel’s targeting of the territory’s telecommunications networks, evidence from Gaza is effectively silent and therefore ceases to exist.

A key aspect of this framing is the UK media’s use of language. Perhaps the most ubiquitous is the use of the term “Israel-Hamas War” to refer to Israel’s ongoing bombardment of Gaza. This is despite the Israeli armed forces’ relentless destruction of civilian infrastructure, including over 42% of the territory’s residential housing units – which was reported as “450 Hamas targets within the past 24 hours.” In accordance with the 7 October chronology, the word “terrorist” is exclusively applied to Hamas, and not to perpetrators of attacks by Israeli settlers on Palestinian residents of the West Bank. Incidents of “Israeli settler violence” are presented in isolation and in the passive: Palestinian residents receive images containing death threats, and then are subsequently killed in their homes by those bearing small arms, chainsaws and axes. The perpetrator, in this instance, is rarely addressed.

Rather than calling out the BBC for its omissions, other UK media outlets have predominantly criticised the BBC for not going far enough, particularly due to editorial’s decision not to refer to Hamas as “terrorists”: The Daily Telegraph printed the words of former BBC Television director Danny Cohen on the front page of its 9 October cover, in which he writes that “This is no time for the BBC or any other news organisation to call terrorism anything but what it is.” In the article, Cohen asks readers to “Imagine if a city such as Bristol or London or Cardiff was invaded by armed men… the BBC describes the actions of “militants” as if shooting children in cold blood is some part of conventional military warfare.” Perhaps the BBC’s current coverage of Gaza is more to Cohen’s taste.

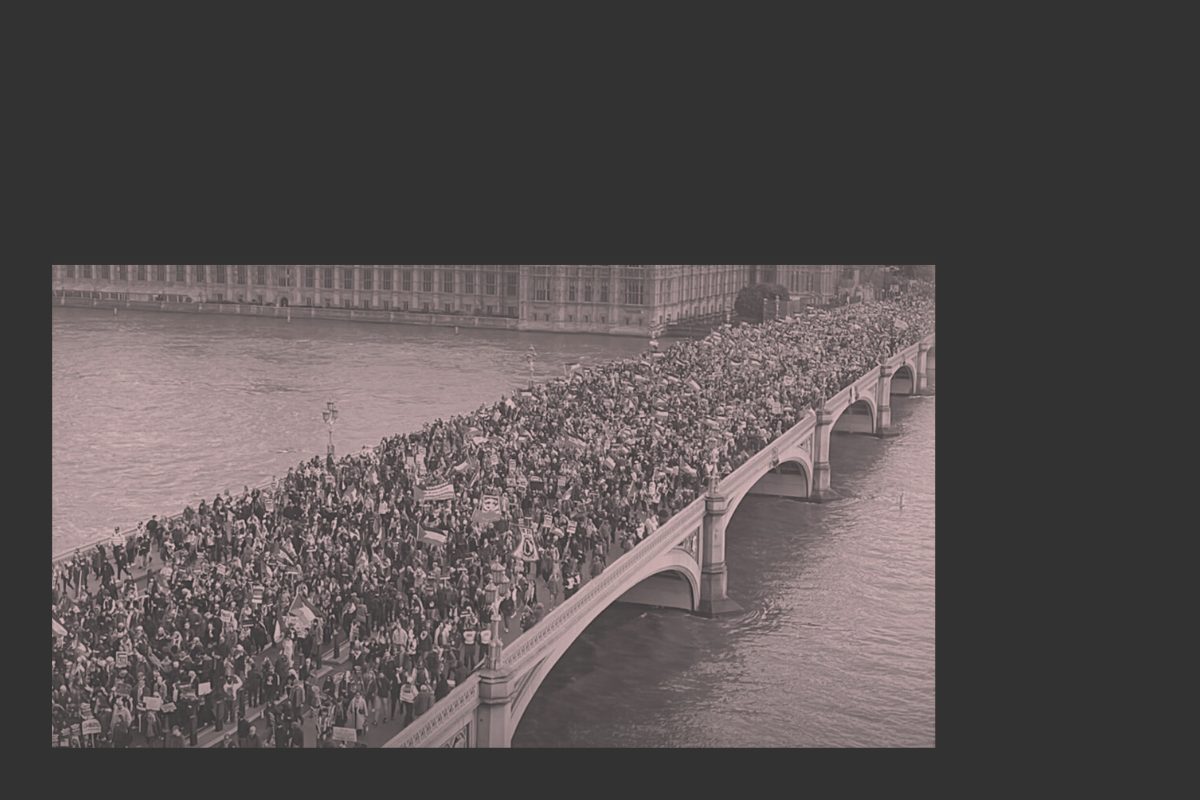

Analysis of sources indicates that the stories which do become part of the UK media narrative are also subject to a significant degree of selection bias. A search engine collection of one of the UK’s more left-leaning outlets, The Guardian, generates 41,300 results for “Hamas attacks”; a search for “Israel attacks” returns 1,510. This is not only related to the recent escalation of conflict: despite thousands of Palestinians having been killed by Israeli airstrikes in recent years, UK outlets predominantly focus on Hamas rockets – even when they haven’t resulted in casualties or significant damage. Are we to assume, then, that the suffering of Palestinians is so relentless and commonplace, that it has ceased to be newsworthy? Likewise, opposition from the UK public regarding government support for Israel has been significantly downplayed, and media outlets are likely to have consistently underestimated numbers of attendees at demonstrations in support of Palestine (for example, on the 28 October, the BBC reported that 70,000 people had gathered in London, whereas organisers and affiliates have given estimates of half a million.)

Lessons from Iraq

It might seem as though such tropes of framing, language and selection bias are simply the result of a media industry which privileges audience demand for particular stories and at a particular pace. However, this notion is dispelled by comparing the current coverage with the UK media’s coverage of Iraq and Afghanistan. The media tropes used in both are concerningly similar: both display military framing, the sanitisation of conflict, and an unequal presentation of civilian casualties, revealing a well-established tactic deployed by UK mainstream media outlets to drive particular narratives of brutal invasions.

In 2003, the BBC commissioned its own study regarding the organisation’s coverage of the US-led coalition invasion of Iraq. Despite having been considered one of the more anti-war outlets, the study concluded that BBC coverage raised “some serious concerns”: that embedded correspondents had given a “sanitised version of war, rather than a full picture”, deliberately avoiding those images considered too graphic for UK audiences. It also commented that the editors had made such extensive use of military framing that aspects of its coverage resembled “a war film,” and that only 22% of BBC stories about the Iraq invasion mentioned Iraqi casualties. The study also found that four significant stories that had been published were later found to be untrue (the Scud attack in Kuwait, the Basra uprising, the Basra tank column and the fall of Umm Qasr), and that half of the claims made in their coverage were not attributed to sources. The deputy director of BBC News at the time, Mark Damazer, responded to the study by warning that the BBC’s “credibility is on the line” and that there was “a significant problem” regarding the outlet’s reporting: “I don’t think we should go down the route of al-Jazeera, but we need a serious debate to establish where the boundaries need to be.”

Thirty years later, the BBC, along with other major UK media outlets, have ignored the lessons illustrated by Iraq: there have already been several publications of unverified or unsubstantiated material related to recent Hamas attacks, including claims of militants beheading 40 babies. BBC correspondent Rami Ruhayem has expressed “the gravest possible concerns” over the outlet’s coverage of the ongoing war, including “incitement, dehumanisation and propaganda” against Palestinians.

The critical difference between the UK media’s coverage of Iraq and Gaza is that of direct UK military engagement. In the case of Iraq, BBC media were granted specific and limited access through the process of embedding journalists within the coalition military. Deploying these same tropes in the context of Gaza highlights the scale of Israeli influence on the UK media landscape to shape the narrative and construct a very particular reality, in which Israeli military intervention is justified, and the destruction of Gaza is a casualty in a resurrected “war on terror.” Any deviation from this particular directive has encountered stringent, corrective criticism: following the BBC’s coverage of the explosion at the al-Ahli hospital, which included BBC correspondent Jon Donnison stating that there was “no possibility” for the cause of the damage as anything other than an Israeli airstrike, the news outlet was shortly afterwards reported to have admitted its “mistake” and “pledged to attribute claims more clearly.” Israeli leadership are themselves aware of their own influence on UK media reporting: on 19 October, Israel’s president, Isaac Herzog, raised “the issue of objective or unobjective reporting about this tragedy” in a meeting with UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, referring explicitly to the BBC’s refusal to refer to Hamas as terrorists – and the BBC’s links with the UK government. Sunak responded by agreeing with Herzog, that “we should call it what it is – an act of terrorism perpetrated by the evil terrorist organisation Hamas.”

Palestinian voices and UK audiences

In such a landscape, the burden is on Palestinians to play within the established rules of engagement which blatantly favour Israeli sources, and where opportunities for voicing their own perspectives are limited. It has become standard format that on the limited occasions where Palestinian representatives are interviewed by UK media channels, they are first presented with the question: “Do you condemn the Hamas attacks on 7 October?” Interviewees themselves, whilst often unaffiliated with Hamas, cannot discuss the impact of Israeli bombardment on Palestinian civilian populations without first navigating their presumed support for, if not involvement in, violent acts of terrorism. The head of the Palestinian mission to the UK, Husam Zomlot, when asked this question during an interview with the BBC, replied: “How many times have you interviewed Israel officials? Hundreds of times. How many times has Israel committed war crimes live on your own cameras? Do you start by asking them to condemn themselves? You don’t.”

Unlike in 2003, the UK media audience has access to social media, including to the wealth of material produced by Palestinian and in particular Gazan journalists, filmmakers and social media accounts such as Plestia Alaqad, Eye on Palestine News, Bisan’8 and Al Jazeera’s Wael al-Dahdouh. Many of these channels and accounts produce content for English-speaking audiences and document perspectives from those on the ground as well as records of specific Israeli attacks. Palestinian journalists, once again, carry the burden not only of reporting but also justifying abuses perpetrated against them (again, particularly difficult when telecommunications networks are sabotaged).

Act now, ask for forgiveness later

Ultimately, whilst influences on UK media coverage can be clearly identified in terms of framing, language and selection bias, comparisons between the coverage of Gaza and that of UK media reporting on Iraq and Afghanistan also raise the question: can any amount of bombardment, destruction and collateral damage of Palestinian civilians ever warrant a change in UK media positioning? There is evidence to suggest shifting sympathies amongst the UK media landscape, although likely due to the extreme scale of Israel’s offensive: yes, “Israel has the right to defend itself” – but to what extent? BBC journalists have recently been reported as “crying in lavatories” and taking unpaid leave due to the outlet’s approach towards Israel as “too lenient”, while “dehumanising Palestinian lives.” We are likely to see a slow shift in language, as observed in media reporting on Afghanistan, where later studies pointed out that “the governments of the United Kingdom and Australia… constantly adjusted their narrative frameworks about what constitutes ‘progress’, while ‘victory’ [was] a term slipping into irrelevance, just as it did during the Iraq war.” Yet the suffering of Afghans left in the wake of the US and coalition invasion and subsequent withdrawal from the country has almost completely slipped from the UK media agenda.

This also begs another – even darker – question as to the purpose of this construction and promotion of particular narratives of sanitisation, militarisation and dehumanisation: are we being prepared for the worst? There is precedent for this: for one, the legacy of the UK government’s dossier on alleged nuclear weapons in Iraq, which was stated to have been “sexed up” for BBC publication in order to promote sympathy for the country’s impending joint invasion. Is it, then, sufficient for UK media outlets to act now and ask for forgiveness later: to commit the same peddling of constructed and biased narratives on Gaza and Israel, only to produce a study later down the line highlighting previous biased reporting, once the overall objectives have been accomplished?

The oft-repeated phrase is that the first casualty of war is truth. But the truth in this case is not only a casualty, but a hostage, and one for which the media is compelled to negotiate. As we remain glued to our screens, struggling to comprehend both the scale of devastation and the sheer volume of information emerging from Gaza, we often neglect the critical questions: why are we being sold a particular story, and where is it taking us?