The recent surge of protests in Syria has rekindled hope for political change in the country. It has also opened the door to wide-ranging discussions concerning the 2011 revolution, encompassing its symbols, slogans and methods, as well as the path that has led the country to its current state of intractability and devastation. But before we delve into that, let’s explore the theoretically viable scenarios for achieving the desired change in Syria.

The first scenario involves peaceful protests and strikes in Syria’s major cities, including – necessarily – the capital, Damascus. This would seek to profoundly disrupt the country, forcing the regime to make concessions and instigate self-directed reforms. Unfortunately, this proved unsuccessful in 2011, and no significant indicators suggest its feasibility and success in the foreseeable future.

The second potential scenario involves the regime accepting a transitional process aimed at halting the severe deterioration in the country’s situation. There is a well-established framework for this process outlined in UN resolutions and international commitments, which include the lifting of sanctions and the commencement of reconstruction once this course is taken. However, there has been no indication from the regime to suggest the possibility of implementing it. Instead, Bashar al-Assad and his associates have conveyed an inclination towards perpetual conflict rather than pursuing this path.

The third scenario entails a shift in regional and international circumstances which could result in the removal of Bashar al-Assad, either by Western powers or one of his allies, within the context of new global or regional arrangements. While this possibility remains constant, there is currently no dependable information regarding the readiness of the conditions for its realization. Syrians have no influence over this outcome, and they will be compelled to contend with its consequences without having a say in how or when it unfolds.

It appears that some Syrians may still believe in a fourth potential scenario: the arrival of opposition militants in the heart of Damascus to overthrow the Syrian regime by force. However, this option is no longer viable today, even in theory, as it would require a miracle: the withdrawal of foreign nations, leaving Syrian militants to fight without direct external support to any party or faction.

We have three theoretical scenarios to consider, then. While the protest movement is currently experiencing a resurgence in Syria, reaching a significant peak with the courageous protests in As-Suwayda that evoke memories of the peaceful revolution in 2011, there are no indications that any of these possibilities are imminent. However, these protests may hold the potential to pave the way for one of these scenarios to be realized, or to introduce unforeseen possibilities not yet apparent.

There is a factor that could come into play and alter the course of events. It involves a substantial shift among the regime’s supporters, particularly among those belonging to the Alawite sect, resulting in the majority of them retracting their support for the regime, and in some cases, actively resisting it. Such a transformation could lay the groundwork for a process of change, either by eroding the core of the regime or completely isolating it. This would demand a lengthy and patient approach, but without it, the prospect for political change in Syria seems limited, except through international intervention, which may never materialize.

The emergence of this transformation necessitates several objective conditions. Among them, there is no place for hastily encouraging people to risk their lives in the streets, nor for the expectations of swift regime change as if by lightning strike. Some of these conditions are created by the regime itself – through its brutality, corruption, and inability to ensure even the basic necessities and dignity for the populace. Others demand coordinated national efforts and favorable international and regional circumstances. Additionally, this transformation necessitates the active engagement of both the current protesters and the masses who played a role in the 2011 revolution, both within and beyond Syria’s borders. Central to these efforts is the imperative to abandon the discourse of “Where were you when we protested?” and abstain from disparaging protesters through superficial comparisons between a “revolution of hunger” and a “revolution of dignity.” It also involves recognizing that holding individuals accountable for crimes from all sides should occur during the political transition as part of a transitional justice program. Furthermore, it requires an acknowledgment that the narrative of the revolutionaries about their revolution may not attain national consensus at all times, and their banners and slogans may not represent all Syrians, not even those who desire the downfall of the regime. Most importantly, it entails a complete renunciation of the discourse of Islamic jihadism and the reliance on its factions, conflicts, and weaponry.

Some supporters of the regime are shifting their stances, and a new generation of young individuals, who were children in 2011, is emerging. Additionally, significant segments of the population who were previously neutral may now find themselves inclined to participate in the struggle for change. It’s likely that most of them won’t join the fight against the regime under the green Syrian flag. In such a scenario, the revolutionaries of 2011 should view themselves as constituents of the broader change movement in Syria, rather than as its sole representatives or spiritual leaders.

This does not mean that we abandon our story and our heritage. Rather, it means that we should be humble and acknowledge defeats, wrong assessments, the passage of time, and the transformations of reality. It means that we remember that the goal is not our own personal victory, but rather liberation from the Assad regime and the closure of its prolonged, bloodstained chapter in history. Afterward, we can embark on the journey towards a dignified life and justice, holding war criminals accountable and constructing a habitable nation.

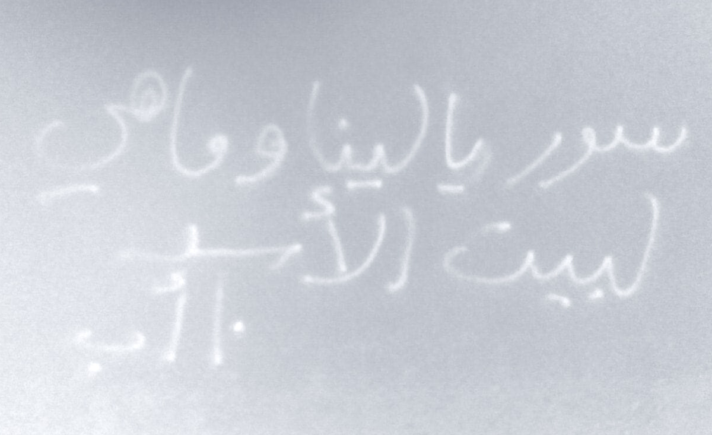

The spirit of 2011 and its slogans are evidently present in the current wave of protests. However, what must absolutely not be present is the repetition of its methods, rhetoric, and gambles. Furthermore, the perpetuation of divisions among Syrians based on their stance should be avoided at all costs. Our priority today is to take steps towards effecting change in our country. We will have ample time afterwards to champion our narrative and its symbols, narrating our story within Syria to those who are unfamiliar with it, as well as to other Syrians who are aware but may deny it, without having the power to silence us through their weaponry and security forces.