As millions of Ukrainians escape from Russian invasion and receive a warm welcome by the European Union and supporters of the “refugee cause,” as well as by Afghans and Syrians who had come here as refugees who expressed a sense of both solidarity but also bewilderment. Surely, those fleeing the war in Ukraine deserve support. But doesn’t this apply to any refugee? Are Syrians and Afghans just second-class refugees? Why can Ukrainians travel for free, while those stuck on Greek islands or on the Belorussian borders barely survive in inhospitable camps or freeze to death? Do Europeans roll out the red carpet for white and Christian refugees, but do everything they can to keep Muslims and People of Color out? Laudable as though it is, does the support for Ukrainian refugees, and even more so the relatively unbureaucratic process with which their situation is handled – they don’t need to go through lengthy asylum processes, can work immediately, can bring their families, to give some German examples – reveal Europe’s racism?

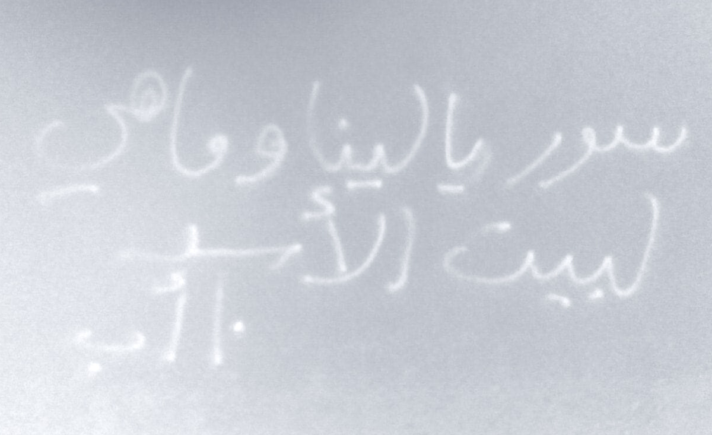

There’s no doubt about the racism that People of Color have to endure in Europe. Reports about Black students being beaten up or thrown off buses and trains when trying to leave Ukraine, about their segregation at the border, have made this abundantly clear. No doubt, this racism needs to be fought, though we shouldn’t forget that there is a long and deadly history of anti-Slavic racism in Europe too. Yet, analyzing the situation through such an anti-racist lens (“Europe cares about refugees if they’re white and Christian, but not if they’re brown and Muslim,” as the cartoon suggests) ultimately conceals more than it reveals, because it ignores politics. And in doing so, anti-racist discourse contributes to the silencing of those it pretends to support.

The support of Ukrainian refugees is only one side of the coin; the other side is the support Ukraine receives to defend itself against the Russian invasion, both militarily and politically. All over Europe, millions flock to the streets, listening to Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, waiving Ukrainian flags, and condemning Russia’s war of aggression. Western countries supply the Ukrainian army with much needed weapons, and have put massive economic sanctions against Russia in place, even if they don’t intervene directly in the conflict. Why? Because this is “our” (the West’s) war. Ukrainians defend our liberty, our democracy, our security. Ukraine is part of Europe, it may even join the European Union soon, not because it’s white and Christian (since Russia is also white and Christian) but because it’s democratic and “Western,” or wants to be at least. Ukraine is part of our political world.

Those fleeing the war receive support because they are our political allies. It’s indeed telling what kind of support Ukrainian refugees do not receive (in Germany): they do not need to go through integration courses where they are supposed to learn about democracy; there are no courses for Ukrainian men (mostly women and children come anyways) where they can learn how to flirt with (Western) women in a respectful way (as have refugees from the Middle East who supposedly had to unlearn their sexist and patriarchal attitudes).

Syrians, or so it seems, do not belong to our political world. We might notice their suffering at the hands of Russian warplanes, we might liken the fate of Mariupol to that of Aleppo (and, not to forget, that of Grozny), we might be aware that Russia tested its weapon systems in Syria. As victims of Putin, Syrians and Ukrainians are alike. But while thousands waive Ukrainian flags and parliaments across the Western world greet Zelensky with standing ovations, those fighting for democracy in Syria received little support, neither militarily nor politically. Their political voices are apparently barely worth listening to, whether in agreement or in disagreement; their struggle isn’t ours. Ukrainians are not only victims of Putin, they are also heroes fighting him; Syrians are not, or so it seems from the Western perspective.

Syrians expressing solidarity with Ukraine are thus also claiming to be part of this “our” political world. They demand being treated as political equals, as partners in the same struggle. To be clear, I’m full of sympathy for such declarations of solidarity. But there is also something tragic about them, because it seems to be one-sided, lonesome solidarity. While Ukraine is also a Syrian cause, the reverse doesn’t seem to be the case. Again, to be clear, this is not to criticize Ukrainians for a lack of solidarity with the Syrian cause. For once, it’s utterly understandable that right now, Ukrainians have their country’s situation in mind. And there are moments of solidarity, such as Taras Bilous’s Letter to the Western Left, quoting Leila Al-Shami’s critique of the Western Left’s silence on Syria. And when a Syrian reported in a Facebook group that he had opened his house to Ukrainian refugees, as he could relate to their suffering, the response by Ukrainians was overwhelming. Yet, this doesn’t change the picture: from a mainstream Western perspective, there isn’t a Syrian cause, much less one that has anything to do with us.

For sure, there are very pragmatic and egotistic reasons for Western countries treating the invasion of Ukraine differently than Russia’s destruction of Syrian cities using the very same forces. It’s simply a much more direct security threat, especially the Baltic and Eastern European countries. It would be foolish to ignore these realities of international politics. Yet, at the heart of different public reactions is a division of the world in a part where politics and the defense of democracy happens, and in a part where war and violence reigns, but that remains alien to our politics.

Criticizing the unequal treatment of refugees from Ukraine and those coming from other parts of the world though an anti-racist perpetuates this division. It sees people as equal victims, all entitled to the same rights and deserving the same kind of support. Yet it does not make Syrians and their struggles part of our political world the way Ukrainians are. It does not help overcoming these divisions. This, however, is what needs to happen.