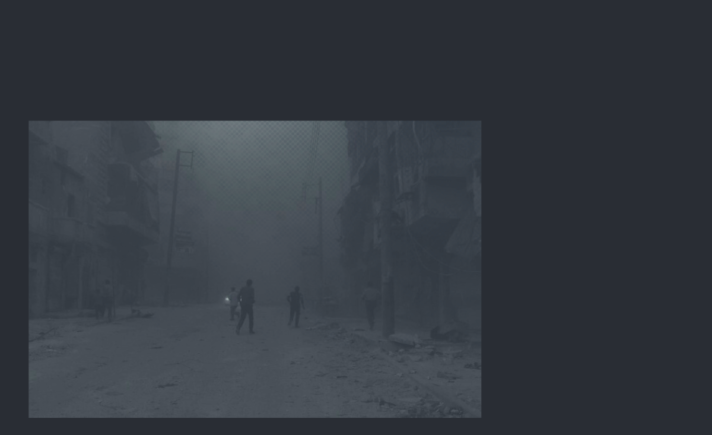

One March morning in 2018, Muhammad Abu Ahmad left his shelter after hearing of a “humanitarian truce” declared by Russia for a few hours. Like others, he assumed the truce would lighten the bombardment on Eastern Ghouta that day.

A brown-skinned man in his thirties, Muhammad hailed from Ghouta’s Kafr Batna town. Anemia had sunk his small, tired eyes in two dark patches. He had a short beard and a thin body—the ravages of life under siege. The first of his three daughters was born two months before the revolution; the second ten days after the chemical massacre of 21 August, 2013; and the youngest during the second round of internal in-fighting. In such terms were events documented in Eastern Ghouta.

Muhammad struggled to start his motorcycle that ran on fuel distilled from plastic waste, now frozen by the cold. After much difficulty, the engine started, and he rode it around the local neighborhoods, alleyways, nearby towns, and the very few relief centers in the area. Though his rifle was on his shoulder, he wasn’t taking it to the frontlines with which he’d become well-acquainted; he was out to fetch bread and food for his children and pregnant wife. The journey would be a chance to gain some clarity of mind and collect his thoughts. Perhaps he’d reach a decision regarding the fate of him and his family: what would he do if he survived and the inevitable happened—the Syrian regime took over all of Ghouta, forcing its residents to choose between “reconciliation” and displacement, as it had done in other regions? Would he accept “reconciliation” and stay in Ghouta? Or would he leave to northern Syria with the displaced?

“Where have they reached?”

Wherever he went in his quest for food, he’d hear the same question: “Where have they reached?” These words, heard everywhere in Ghouta at the time, referred to the Syrian regime’s forces and their allies, who had begun a long-anticipated ground invasion at the start of the month, in an escalation of their most ferocious assault yet on Ghouta, formally launched on 18 February.

The campaign saw the Assad regime successfully break through rebel defenses and gain ground from Ghouta’s rural eastern fringes. Rapid gains followed in Nashabiya and Hazrma, succeeded by more gradual conquests in Otaya, al-Hawash, al-Shayfuniya, and al-Rayhan to the north, as well as Aftaris, al-Muhammadiya and Mazari Jisreen to the south. This brought the ground battles and frontlines to the edges of Ghouta’s densely-populated major towns and cities, changing the nature and tools of the fight.

Shortly afterwards, as the frenzied bombardment resumed, Muhammad returned with half a kilogram of flour and a kilo of lamb meat—the most affordable kind of food still available in Ghouta at the time. The lambs that had lost their grazing ground could obviously not feed on cement. The butchers’ blades were closer to their necks than any grass.

Muhammad shouted through the basement door for his wife Umm Ahmad, calling down to her place of refuge, hoping his voice would find its way to her amid the din of chatter and crying babies in the collective shelter he had chosen on the advice of Bassam Dafdaa, the “Sheikh of Reconciliation.” This was one of several shelters designated “safe zones” by the Sheikh; places that wouldn’t be bombed, and would face no repercussions if regime forces were to enter the town. Naturally, these were later shown to be empty promises.

Before the regime advanced on the ground, there was a violent prelude of heavy bombing of vital civilian areas with all sorts of weaponry—both legal and prohibited—targeting every facet of life. This bombing continued non-stop for fourteen days, then escalated with a ground invasion that made perfectly clear the regime’s intention to destroy the entirety of the area’s infrastructure.

Muhammad’s family spent most of these days in the basements. He would occasionally leave at night to look for food, vital necessities, and a source of electricity to charge his phone. Such sources might be solar panels charged in the daytime, or small electric generators. He tried to keep his phone connected to the Internet, despite the bomb-damaged line, to stay up to date with the local news. He kept an eye out for any reports or information that might help him decide between his limited set of options.

The regime’s advance and the rapid collapse of the frontlines led to the dense concentration of civilians and fighters in shrinking pockets of territory that were continuously being destroyed and rid of all vital necessities. This was all on top of several years of choking siege, which had already brought severe shortages of food, water, healthcare, medicine, heating, and essentially all means of survival. Such exceptional pressure caused the fighters to lose their discipline, morale, and determination, and their main motivation to fight: the defense of civilians. They were simply incapable of protecting their families from the most brutal military campaign conceivable.

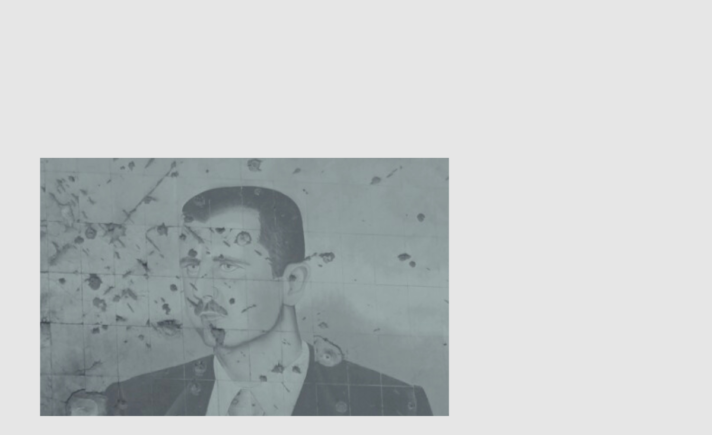

In parallel with all this, major internal destabilization was underway within the neighborhoods still in opposition hands in Ghouta, encouraged by the regime through its supporters and proxies among local religious figures and party members both inside and outside the area. These figures called on civilians and fighters to hand over their territory and cease fighting in exchange for guarantees of safety and the possibility of recruitment into regime forces along with a pardon and certain privileges. This successfully prompted many fighters to surrender and exit Ghouta with their families through so-called “humanitarian passageways” established by Russia and the regime. Ghouta thus witnessed the surreal spectacle of besieged victims escaping the hell of bombardment by the regime and its allies into the arms of the selfsame regime. In this chaos, only few fighters—most of them highly ideological—remained on the hopeless fronts lining the peripheries of Ghouta’s most crowded cities and towns. Their sole purpose was to slow the regime’s advance, while waiting for who knew what.

Kafr Batna, Muhammad’s hometown and world, is the center of a wider district by the same name, comprising a large segment of Eastern Ghouta known as the central sector. Despite several military frontlines and points of contact between Kafr Batna and regime territory to the south along the Barada River, the regime didn’t attempt a ground advance from this direction in its final campaign. Instead, it shelled the interior of the town and tried to enter it from the east, after taking the town of Jisreen next door.

These new eastern frontlines in Kafr Batna were not as fortified and well-equipped as those along the Barada. The few fighters there were disorganized locals and youths, though some of them had previously fought in formal rebel factions. These factions tried to send them assistance from other areas, but for each fifty men sent over, only two or three would reach the frontlines. The others would slip away, seeing no point in fighting, and being more concerned with their hungry families and children in the basements and bomb shelters, who would have no one looking after them if they went off to the front. These were moments when a man would abandon his own brother, as though Judgment Day were underway in Ghouta.

Inside the town, in parallel with Sheikh Bassam’s work to gather people in places close to his residence, a center was opened to register the names of those who accepted “reconciliation” and those who rejected it in favor of displacement. This initiative was intended to catch the local opposition off guard, given their refusal at the time of all offers to negotiate, including offers mediated by Sheikh Bassam.

In light of the factions’ opposition to these propositions, it was clear that Sheikh Bassam’s initiative to register these names was pointless, and not a constructive step toward ending the catastrophic situation in the area, nor even a means for individuals to save themselves. Nonetheless, it drew a large turnout, especially after the massacre in Kafr Batna on Friday, 16 March, in which dozens were killed and wounded, even after rumors were circulated by Sheikh Bassam’s supporters to the effect that Kafr Batna was secure, and that the areas designated by the sheikh were safe havens for civilians. These had led many of Ghouta’s people to move to Kafr Batna, and prompted those hiding in the bomb shelters to resurface and flood the streets in the hopes of doing all they’d been unable to throughout the preceding days of terror.

Muhammad carried his rifle, which hadn’t left his shoulder throughout the campaign. He stood at the entrance of the shelter where his wife and daughters were hiding. Sheikh Bassam’s offices were on the same street, now crowded with throngs arriving to choose their fate. Muhammad tried to find a spot to stay at the door of the shelter without getting in the way of the column that stretched from the middle of the street, by the sheikh’s offices, to well beyond the shelter’s entrance.

A single queue united those seeking to “reconcile” with the regime and stay in their homes with those refusing the offer, preferring to leave. Muhammad found himself in the thick of this crowd, stepping slowly toward the sheikh’s center at the front. This center consisted of two offices, each representing one option. There was no third option. While Muhammad inched forward, he summoned all the possibilities, ideas, and memories his mind could conjure, hoping these might help him select the right office at the end of the queue; the office that would determine his and his family’s fate.

From glassmaker to medic to fighter

At the start of 2011, Muhammad was a young newlywed just beginning his adult life, working in glass production, which provided him a reasonable income. When the protest movement began in March, he wasn’t initially spurred into action; he was broadly content with his lot. For months, the revolution continued without him paying it much heed. Those who joined the revolution faced mounting repression and violence, and sweeping security campaigns began in Ghouta. By the end of the first year, businesses, shops, and factories began closing down and the area was placed under partial siege.

Muhammad was eventually moved to action by a sense of regional identity as he watched his neighbors being injured, killed, and arrested. He started secretly (and apprehensively) helping the uprising, using the small car he had recently bought as an ambulance for the wounded. As the bombing, violence, and siege intensified, Muhammad continued to work with a medical unit, providing him with a means of obtaining basic necessities.

When the infamous chemical massacre occurred on 21 August, 2013, Muhammad’s medical unit assisted whomever it could among the victims. He behaved heroically; not sleeping for over twenty-four hours while continuously transporting the wounded and dead, before suffering the debilitating effects of the Sarin nerve agent himself, only recovering after a week in bed.

After eventually losing his car under the rubble of a building struck by regime fighter jets, Muhammad ceased working in the first aid field. Instead, he joined one of the local armed brigades, spurred by his heightened feeling of regional belonging and his need for a source of income to support himself and his family.

For months, he moved between various frontlines along the borders of his town and others next to it, battling against regime forces. He was fully immersed in the armed struggle, assuming the role that was in some sense imposed upon him. Disputes broke out between local brigades along ideological and partisan lines, but he paid them little heed. His sole concern was fighting for the faction he felt best served the interests of his town and community, and his own survival. As such, he shifted between various different groups, balancing the need to stay with his communal peers and his need to support his family financially.

Muhammad was injured twice: first during a battle with the regime, and then in a confrontation with a local faction that tried to raid his town. Neither injury kept him away from the fight, to which he had now grown accustomed. It became his profession, at a time and place where professions were few and far between. Alongside his earnings from the faction—a meager, irregular income and a daily meal he brought home to his family—his military status in the community offered him further opportunities. These took the form of firewood for heating gathered from trees on the frontlines, for example, or furniture and household items and plastic (the “oil of Ghouta;” essential for distilling fuel) taken from empty homes, or anything else encountered in any place reached.

For this conduct, Muhammad battled feelings of remorse, which he tried to banish with dishonest rationalizations. Though what he was doing may have been theft, it was euphemized as “weeding” during the siege; the mildest term people could find for it, which may have been coined by the religious preacher employed by his brigade. This preacher would occasionally show up at the fighters’ bases to offer sermons and guide them to the virtuous path. The fighters in turn would choose to listen to the part most pleasant to their ears: “necessity permits the impermissible”—the most convenient religious precept for the survival in the area.

And the factions indeed survived. Despite the steady decline of their popular support owing to their repeated transgressions, violations, and conflicts, they continued to benefit from the catastrophic consequences of the siege, which pushed many to find any available means of staying alive, including joining these same factions. By the time the battle in Ghouta reached its final peak, the fighters were not the same people they’d been a few years previously. Most had become creatures of stone, driven by need rather than conviction, governed by despair and hopelessness, robbed of opinions and decisions, concerned only with escaping their situation.

With the continued bombing and advances by the regime towards Kafr Batna, the opposition factions, as well as many civilians, began withdrawing to the last remaining areas on Ghouta’s western front. These factions left behind a lot of fighters, some of whom had decided to stay and accept their fate in regime hands. Others hadn’t yet made up their minds, especially since it was still unclear what would happen to the remaining opposition-held neighborhoods. Would they be displaced, or annihilated entirely? After the regime took Kafr Batna, and announced the displacement agreement and the end of military operations, many of those who had stayed were able to smuggle themselves out to where the buses were waiting to relocate families to northern Syria.

Based on what I saw first-hand living with Muhammad in those days, and what he told me from time to time, I would say his decision was reminiscent of the dilemma faced by Sartre’s French student, who had to choose between joining the Free French forces to avenge the Germans’ killing of his brother, or staying with his mother to help her survive.

What ethical system could help Muhammad make his decision? Religion? Which religion? Which doctrine or interpretation? Both choices might be permissible, depending on these variables. Moreover, religious discourse of all kinds had already lost its charm and influence on the youth, given how many clerics had stood by the regime, while the clerics who did oppose the regime had waged internecine battles reaching the point of bloodshed.

Equally, there were no alternative ethical systems for Muhammad to rely on to make his choice. No philosophy or ideology could have guided a young man with a modest level of education, nor could abstract moral values offer the clarity required to help make such a pivotal decision. All that remained to guide him was a combination of deep-set instincts and emotions.

As such, Muhammad ignored all the values wrestling one another inside him and let his feelings decide. He loved his family and mother, as well as his hometown and its people, and so chose the option dictated to him by his emotions. He was also given numerous guarantees by Sheikh Bassam and others that he and his family would be unharmed. He decided to remain in Ghouta under regime rule, supporting his family and elderly mother, even though he knew the decision could mean aligning with the regime, and even fighting alongside it.

Sure enough, “Muhammad Abu Ahmad”—not his real name—was drafted into Assad’s reserve forces eight months after Ghouta fell and he “reconciled” with the regime. Perhaps he was later transferred to the northern frontlines in Idlib, to face his former neighbors now displaced to the same region. Despite this cruel fate, Muhammad may have been among the lucky ones: many of his old comrades were arrested after the “reconciliation.” His own choice to “reconcile” was one he was unable to defend to me except with the following confounded words, the last I ever heard from him: “To whom will we leave the country?”

[Editor’s note: The above article was originally published in Arabic on 15 January, 2019, as part of Al-Jumhuriya’s Fellowship for Young Writers.]