[Editor’s note: This article is part of Al-Jumhuriya’s “Gender, Sexuality, and Power” series. It was also published in Arabic on 6 December, 2018.]

In the summer of 2017, as (unfounded) rumors began to spread on social media of Syrians “going to protest against our honorable army,” a wave of hyper-masculine ultra-nationalism mixed with the usual xenophobia saw random Syrian men targeted by Lebanese men. Videos of Lebanese men filming themselves angrily beating Syrian men in revenge attacks went viral, and the already-intensifying talks of expelling Syrian refugees found themselves, if only for a few days, reaching the mainstream (they have since become even more normalized). Many rightly denounced these videos, but few were those who pointed out that the violence inflicted on Syrians was not just rooted in a quasi-racial sense of superiority, reflective of the otherwise fragile sense of nationalism that the Lebanese themselves often mock, but in the Lebanese idea of masculinity as well.

The topic of Lebanese masculinity has not been widely studied and is in itself an almost-impossible topic to approach in its entirety, given the difficulty of even defining the subject being studied. Does ‘Lebanese’ include only those lucky enough to get the difficult-to-obtain citizenship, itself often a sectarian calculation? Do studies exclude, for example, Syrian and Palestinian refugee men who have been in Lebanon for several years? What about those who are half-Lebanese, half-Palestinian, or those who have a non-Lebanese father and a Lebanese mother, and therefore don’t have the citizenship? Does the topic pre-suppose a cis and heterosexual subject? There are no good answers to these questions, but for the purpose of this essay, we will focus on what I believe is the dominant form of masculinity in Lebanon, and how it affects those who reside in the country.

In his essay The (Little) Militia Man: Memory And Militarized Masculinity In Lebanon, Sune Haugbolle speaks of how Lebanese artists who seek out a redemptive narrative on former militiamen who fought during the 1975-1990 civil war show them as regretful, even feminized, “little men” on par with other human victims of a senseless war. This is meant to “sever the link between masculinity and sectarian cultures that, still today, celebrate violence committed during the civil war.” In other words, masculinity in Lebanon is often linked to social constructs created or at least consolidated during the war, which, to quote Ralph Donald, is in “itself is a gendering activity, one of the few remaining true masculine experiences.” This is additionally relevant as the figure of the ‘militiaman’ was taken to “represent various structural explanations of the war” (Haugbolle, 2012 and Najib Hourani, 2008) as though it is through the figure of the ‘militiaman’ that the whole war could be understood.

Therefore, as (among other factors) narratives from and on the civil war remain unaddressed at the national level nearly three decades since its end, expectation of violence as an inherent part of masculinity remains widespread in Lebanon. In his recently-released book, Lebanon: A Country in Fragments, Andrew Arsan recounts the story of a former militiaman-turned-bodyguard of a Lebanese political boss (za’im) who, as soon as he heard of a violent but quickly resolved quarrel between his za’im‘s son and members of a rival party, “took to the roof of the apartment building in which the za’im and his family lived” and “lay down on the roof edge like a sniper, Kalashnikov ready” while muttering “they’re coming, they’re coming.” What was revealing was how the episode was recounted by those who knew him. The za’im‘s wife exclaimed “the poor man!” as though it was a pitiful occurrence, while the za’im‘s drivers found it amusing (“he was possessed,” “insane”). Besides their different interpretations, what was missing in their reactions is the element of surprise. No one was astonished by what the former militiaman did. It didn’t raise any eyebrows, nor was it viewed as particularly unusual. It was “normal.”

Indeed, it is ‘normal’ to expect outbursts of violence in Lebanon, often coupled with grand displays of toxic masculinity and, often still, with sectarian/conservative pronouncements. This is, after all, the country where former sectarian warlords, all men, and their allied clientelist class, overwhelmingly men, continue to maintain near-complete control over the country’s political and socio-economic life. They are our president, prime minister, speaker of parliament, most of our MPs and all leaders of political parties. Of the 128 members of parliament recently elected, only six are women, and even the minister for ‘women’s affairs’ is a man. Taking this into consideration, recent progress by women’s rights activists and/or LGBTQ+ rights activists in putting cracks in the decades-old patriarchal system is particularly laudable. From shy but steady advances in LGBTQ+ rights to the repeal of the infamous ‘marital rape‘ law which allowed rapists to avoid prosecution if they married their victims, there is no doubt that the work of these women and men is bearing its fruits. In addition, although only six were elected, a record number of 86 women ran during the 2018 parliament elections.

Perhaps sensing the way the wind was blowing, or simply re-asserting their authority, members of that patriarchal-sectarian/warlords elite have for years been mobilizing against the movements for gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights. In March 2017, Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah spoke out against the women-led campaign to ban child marriage, before demonizing Lebanon’s LGBTQ+ community and accusing them of “destroying societies.” Given that, “as the intensity of religiosity in party platforms rises, the share of women in leadership bodies falls,” as Fatima Sbaity Kassem argued, it is perhaps no surprise that Hezbollah was the only Lebanese party in the recent elections to have no women candidates, although the other sectarian parties were not exactly impressive either: tellingly, the overwhelming majority of women running during the 2018 elections were doing so independently or as civil society candidates.

Nasrallah’s comments are part of a wider tendency among politicians and the sectarian elites to portray gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights and, broadly speaking, feminism as some kind of ‘foreign’ (here meaning Western) import. In May 2017, members of the League of Muslim Scholars (Ulemas) in Lebanon threatened to protest should any event on the occasion of the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia (IDAHOT) take place. IDAHOT organizers and participants were the victims of a “campaign of pressure, intimidations and even threats by a number of Muslim authorities.” They also faced opposition from Christian groups as members of a Christian Orthodox group issued a call to their followers to “pray against the threat of homosexuality.” In 2013, Marwan Charbel, then-Minister of Internal Affairs, said that Lebanon should consider banning French homosexual tourists (shortly before same-sex marriage was legalized in France), using the Arabic equivalent of the ‘faggots’ slur as well as implying that Lebanese homosexuals don’t exist. Also in 2013, the mayor of the Dekwaneh suburb east of Beirut, Antoine Chakhtoura, ordered a police raid on a LGBTQ+-friendly club, describing one transgender woman as “half-woman and half-man,” adding, “I do not accept this in my Dekwaneh.”

I could go on.

This reality contradicts the way Lebanon is often portrayed in relation to the Arab world, namely that of a progressive or liberal beacon, even a safe haven, within a conservative region, particularly with regards to gender and sexual orientation. On the surface, the results of the International Men and Gender Equality Survey, or IMAGES, survey would seem to confirm this. For example, 75% of men in Lebanon “think there should be more women in positions of political authority” and ‘only’ 26% of men in Lebanon agree with the notion that a woman should tolerate violence “to keep the family together.” This is in stark contrast with the 90% of Egyptian men who say women should tolerate violence and the 29% of Egyptian men who say that there should be more women in positions of political authority.

With such progressive views apparently so widespread, how can we explain the low participation of women in political life? Or the fact that, of the six women elected, only one was neither related to existing male politicians nor a member of a sectarian party? These questions are part of the reasons why when I read the above statistics, I had to read the full report. My skepticism turned out to have some merit. Indeed: “When asked about their support for women in various public positions, men were most likely to express support for women as heads of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and least likely to express support for women as religious leaders, heads of political parties, heads of states, and military officers.” Unsurprisingly, men were also “less likely to express comfort with having a female boss” (at 74%, compared to 92% of women). In other words, women could hold some form of power, but not in places that could actually challenge existing power structures.

These results are further explained by the deep connections between patriarchal structures and the country’s notorious sectarian (or ‘confessional’) system. Indeed, Human Rights Watch’s 2015 report entitled Unequal and Unprotected: Women’s Rights under Lebanese Personal Status Laws explains how the lack of a unified civil code regulating personal status matters affects women disproportionately. Rather than one civil code, Lebanon has 15 separate personal status laws for the country’s different recognized religious communities. And when Human Rights Watch reviewed 447 legal judgments issued by the various religious courts, it found (unsurprisingly) “a clear pattern of women from all sects being treated worse than men when it comes to accessing divorce and primary care for their children (“custody”).”

To understand how deep the ties go, consider the recent comments by the director general of the Ministry of Public Health regarding abortion: “There will never be any law legalizing abortion, quite simply because the religious authorities will never authorize it. Also, it is not our priority in terms of public health.” With a cabinet that includes almost no women, is it a surprise that women’s reproductive rights are routinely dismissed in Lebanon? Needless to say, this horrific reality has forced women to risk their lives to get illegal abortions, which has also disproportionately affected working-class women—the country’s majority—and rendered them vulnerable to abuse. In 2016, it was revealed that 75 Syrian women were held as sex slaves and had 200 abortions performed on them by a Lebanese doctor before being released. Had these women managed to escape to seek help, and had they wished to get the pregnancies caused by rape terminated, they would have been prevented by law from doing so.

The links between sectarianism and patriarchy were also expressed by Gebran Bassil, Lebanon’s foreign minister and son-in-law of the president, who, when asked about the right of Lebanese women to pass on their nationality to their spouses and children, replied that he would consider supporting it as long as it explicitly excluded those married to Syrian and Palestinian men, adding that this was necessary to “save Lebanon’s land.” Given that most of these men are (non-wealthy) Sunnis, his answer reveals the widespread sectarian calculations made by Lebanon’s political class—his party, the Free Patriotic Movement, draws its voting base from Lebanon’s Christians and their major allies, Hezbollah and Amal, from Lebanon’s Shia—and, to a considerable extent, Lebanese society at large. Here we can see the link to class as well: while Bassil rarely goes a week without repeating that he will never allow Palestinians (let alone Syrians) to become naturalized as Lebanese citizens, he supported the naturalization of over 300 people, allegedly mostly wealthy Syrian businessmen with ties to the Assad regime.

The picture is incomplete, however, without adding how vulnerable groups become racialized. As Alli, a social worker with the Anti-Racism Movement (ARM), recently told me, “black women’s bodies are very commonly seen as targets of verbal and physical harassment.” This was shortly after two Kenyan women were beaten in broad daylight by an off-duty Lebanese soldier. Soon after, rather than the perpetrator facing justice, one of the Kenyan women, Shamila, was deported instead. The relevance of this story lies in the fact that migrant domestic workers are an inevitable part of Lebanon’s gender dynamics, given that out of the estimated 250,000 working in Lebanon, the overwhelming majority are women. In the houses where they live, they are the ones performing ‘traditionally feminine’ household tasks and their role in Lebanese society has the potential to threaten the status quo as well. In 2015, the Lebanese state rejected the creation of a Domestic Workers’ Union, despite it meeting all legal requirements. A well-organized union has the potential to challenge the country’s notorious ‘Kafala’ (sponsorship) system, which ties a migrant worker’s legal status to their sponsor and renders them vulnerable to abuse.

And yet, migrant domestic workers are often excluded from national narratives on women’s rights due to their race, gender, nationality, and class. This is despite the fact that, according to the ILO, domestic workers are among the global workforce’s most vulnerable to violence and abuse, partly because of their physical isolation, hidden behind the closed doors of private residences. This is in addition to the Lebanese state de-facto criminalizing their womanhood: Between 2016 and 2017, at least 21 migrant domestic workers were detained and deported for the crime of having children in Lebanon, along with their children. As justification, Lebanese authorities said the women “were not living with their employer or were not supposed to give birth in Lebanon.”

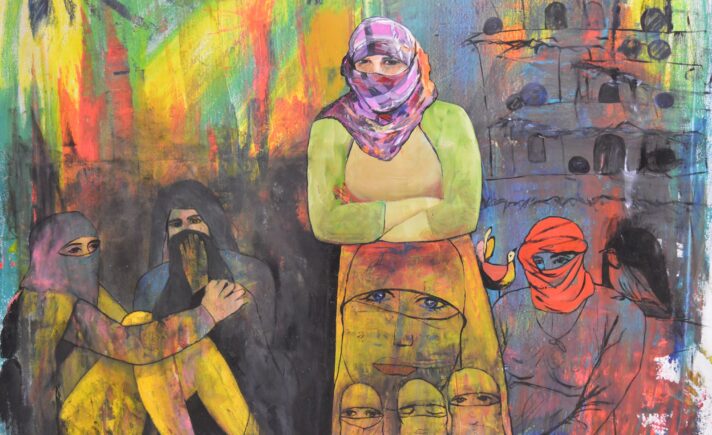

In a country politically dominated by what I call a patriarchal-sectarian-warlords class, is it so surprising that basic rights such as women’s reproductive rights and their right to pass on nationality are absent in Lebanon? Is it so surprising that racialized women—here defined as working-class women from countries such as Palestine, Syria, Sri Lanka, Sudan, the Philippines, and Ethiopia—are viewed, when viewed at all, as potential ‘demographic threats’? Lebanon, despite officials’ denials, is still living in the shadow of its own civil war. As the militarized masculinities forged or solidified during the war continue to dominate discourse, they have found company in widespread discourses demonizing those who don’t fit within the rigid gender binaries and sectarian/class calculations upon which the foundations of this so-called delicate ‘sectarian balance’ of post-1990 Lebanon inevitably rest.