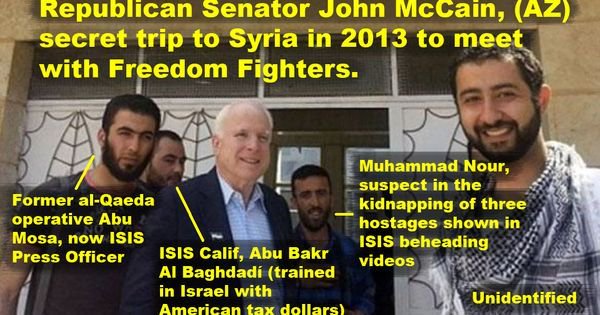

If one image sums up the marriage of “War on Terror” discourse with self-styled “anti-imperialism,” it is a widely-circulated doctored image of the late John McCain in Syria meeting with members of the Syrian opposition. McCain went to Syria in 2013 in his capacity as a US Senator. The image of him smiling with several unidentified Syrian opposition figures has since made the rounds on the Internet, photoshopped to mislabel the figures accompanying McCain as a series of Islamic State (ISIS) leaders, including the infamous self-declared “Caliph,” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Additionally, the photo erroneously claims al-Baghdadi was trained in Israel with US tax dollars. Nevermind that the labels are false; the image circulates anyway and feeds on people’s fears that larger powers are manipulating the conflict in Syria for their own ends, which is most certainly true. The average Internet user can easily slip into believing these Syrian men are indeed ISIS leaders, and that Baghdadi is really a US/Israeli agent, as the accusation fits vaguely into an existing framework, one in which “imperialism” is willing to arm and train many questionable groups and individuals for short-term geopolitical gain. As will be seen, this is only one of numerous examples of War on Terror discourse misrepresenting complex conflicts as black-and-white battles against “terrorism,” irrespective of the actors using it, with human rights violations and civilian deaths the inevitable result.

In an interview from June 2018, the fraught Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad described the forces opposing him as “…mainly the West, led by the United States and their puppets in Europe and in our region; with their mercenaries in Syria, they try to make it farther, either by supporting more terrorism, bringing more terrorists coming to Syria, or by hindering the political process.” Assad’s repeated statements about “terrorism” show he speaks of the entire opposition as terrorist proxies for foreign states. One should expect little more from a dictator who inherited rule over an entire country from his father, and who has brutally imprisoned, tortured, and killed thousands of Syrians. Yet, such discourse has been parroted, and in some cases made yet more extreme, by “anti-imperialists” in their defense of the Assad dynasty against what they insist is a Western-initiated war of regime change. By repurposing “War on Terror” discourse in the service of “anti-imperialism,” these actors attempt to cast away the problems with such broad accusations of terrorism, convinced of their accuracy and justice on the grounds of challenging imperialism.

For example, one episode of Moderate Rebels, an ostensibly anti-imperialist podcast, titled “Syria is not Palestine; anti-Salafi/Wahhabism is not Islamophobia,” illustrates this position well. The very name Moderate Rebels, indeed, is a jab at the idea that any part of the opposition to Assad is not extremist. The writers Max Blumenthal and Ben Norton, who co-host the podcast, spoke with fellow “anti-imperialist” Rania Khalek and attempted to address the accusations that they parrot War on Terror discourse, among other criticisms.

In explaining his complete U-turn on the issue of the war in Syria (he had previously written critically about the regime), Blumenthal says at first he “imposed his understanding of Palestine, projecting it onto the Syrian situation… I also imposed my understanding of Islamophobia in the West onto the Syrian situation…” Blumenthal’s comments show he struggled to reconcile his position on Palestine with his position on Syria, in a manner that focuses on the states involved and not on the peoples. Indeed, the entire discourse around the War on Terror as a tool of imperialism prevents Blumenthal from seeing Israel and Syria as states repressing their subjects, in that peoples are struggling against states for independence and self-determination. In the same podcast, Khalek dismisses the idea that she is using War on Terror discourse by emphasizing how terrible and heinous the acts of groups challenging Bashar al-Assad are, which is exactly what one must do when siding with a state against people. To this author’s mind, none of what Khalek describes did not happen; rather the problem is that she and the others speak of the entirety of the opposition as if its worst, most extreme facets constitute the whole. Assad’s state sought just such an outcome at the beginning of the uprising, evidenced by its release of thousands of prisoners it had previously jailed for membership of extremist groups (see here and here.) Khalek embraces and repeats the exact logic used by Assad, namely that Syrians must choose between having him as dictator or “terrorists” running Syria. At any point from 1970 on, it was possible for the Syrian state to democratize and transition away from autocracy. Instead, it developed a cult of personality around the president and brutally repressed opposition figures, especially but not exclusively Syrian Communists. War on Terror discourse is now central to the Syrian state’s proclaimed legitimacy.

“Terrorism,” however defined, clearly did not begin with 9/11, but the discourse surrounding the term took a dramatic turn in the wake of the infamous attacks that shook the United States, and indeed the entire world. For our purposes here, “terrorism” may be defined as the use of violence against civilians to achieve political and/or ideological goals. By this definition, states can commit terrorism, as can non-state actors, a distinction necessary to avoid merely demonizing just causes and groups. Then-US President, George W. Bush, launched the Global War on Terror in 2001, in response to 9/11. The event remains surrounded by conspiracy theories proclaiming that the US was ultimately behind the attacks. This shadow of doubt and conspiracy lingers around jihadist terror to this day, intimating that it is ultimately the US animating and supporting these extremist groups. US and Coalition troops invaded Afghanistan in late 2001 and Iraq in March of 2003, both as part of Bush’s declared War on Terror. A global infrastructure consisting of numerous black sites, Guantanamo Bay prison, and later a program of drone assassinations are some of the most infamous facets of this War on Terror, sweeping up many individuals, disproportionately Muslim men or men from societies in which Islam is a predominant part of culture and life.

One effect of War on Terror discourse from the US state and its implementation was to racialize Muslim men as evil and extremist. Hollywood and popular media representations fed the stereotypes of Muslim men as angry, bearded jihadis who needed to be fought and killed by valiant white American soldiers. “24” and “Homeland” are both examples of popular television shows deeply steeped in such racialized representations of Muslim men. The cumulative effect of policy and popular media conflated brown men of non-Muslim backgrounds with Muslims, racializing them together under the umbrella of ‘terrorist brown men.’ Examples include a Sikh temple in Wisconsin that was the target of domestic terrorism in the USA, killing six; the heckling of a left-wing Canadian Sikh politician named Jagmeet Singh in Ontario, Canada, by a woman who accused him of being “in bed with sharia” and the Muslim Brotherhood; and a Texas branch of the Republican Party that recently came close to voting out its member simply for being Muslim. These are just a few instances, both violent and non-violent, of War on Terror discourse demonizing innocent civilians. Even if directed at groups or individuals genuinely guilty of engaging in terrorism, War on Terror discourse inevitably bleeds outward and stains an even broader swath of people. This overgeneralization parallels the way Islamophobia and racism in general function, negatively stereotyping entire groups as a means of exercising power over them.

In the years since Bush launched his War on Terror, numerous authoritarian states have adopted its discourse for their own ends. China has sought to conflate Uighur separatism with the “Global War on Terror” since 9/11, deliberately embracing talking points used by Washington in its effort to paint Uighurs as Islamic terrorists. Vladimir Putin, similarly, saw an opportunity to align with the US and present Russia’s long-running war against Chechen separatists as part of the Global War on Terror. More recently, Russian officials have referred to groups in Syria challenging the Assad regime as “terrorists,” especially those killed by Russian forces. “We have killed, we are killing, and we will kill terrorists…whether that be in Aleppo, Idlib, or other parts of Syria,” Russian government spokesperson Maria Zakharova said in comments in late 2018. Such remarks are in line with Moscow’s support for Assad and his use of War on Terror discourse. The Syrian Civil Defense, a volunteer rescue organization also known as the “White Helmets,” has been repeatedly tarred as “terrorists” and a “tool of Israel.” As in other parts of the world, the “terrorist” label is meant to delegitimize, to push an individual or group beyond the pale of respectability. Russia and China both deployed rhetoric against “terror” prior to 9/11 (and, indeed, had real problems with separatist violence). Both used Bush’s declaration after 9/11 to launder their countries’ issues with separatist violence, presenting the problems as local manifestations of the Global War on Terror.

Buried just under the surface of the term “terrorist” for anyone willing to look is a debate about statehood and sovereignty. States have armies and, thus, recourse to “legitimate” violence, assuming they follow international law pertaining to when and how they engage in war. For non-state actors, however, the nation-state system adopted worldwide allows no legal recourse to violence, and such non-state groups are frequently labeled “terrorists” by their opponents when they attempt to wield violence for political ends. Russian President Vladimir Putin gave a nod to this ongoing debate over the moral, rather than analytical, definition of terrorism in remarks made in 2004, questioning the use of the term “terrorist” and calling for a coherent definition that would be equally applied without double standards. Of course, from a state’s perspective, separatist and nationalist movements challenging state sovereignty are illegitimate, and therefore “terrorist,” not to be debated or tolerated. Groups of this kind around the world are frequently championed by anti-imperialists as legitimate representations of popular will and challengers to larger power structures, and indeed many are. Their exclusion from legitimate violence by international law and their targeting by the states they challenge means they are often correctly understood as oppressed peoples, not terrorists. This is exactly the position that Blumenthal, Norton, and Khalek take on Palestine—one I share with them. Unfortunately represented in such disagreements, the question of how to define terrorism remains unanswered in policy or international law to this day, nor does it seem likely to ever be resolved. The term is too situated in power relations, subjectively understood, to be to used objectively and agreed upon.

A central facet of using War on Terror discourse is linking local conflicts to larger international terrorist organizations. China, Iran, and Russia all have separatist movements which challenge state sovereignty and seek anything from autonomy to national independence. The Uighurs in China are a Muslim minority, currently making headlines around the world due to Beijing’s policies of mass arrest, detention, torture, and re-education as part of its own War on Terror against this religious/ethnic minority group. The scale of China’s crackdown on Uighurs involves a large infrastructure of camps and detention centers, reminiscent of dark times in the twentieth century. Convinced that these events are not real, or nowhere near the scale reported, the same Norton, along with fellow traveler Ajit Singh, published a piece denying that China is building or using detention camps for Uighur Muslims, arguing that the media reports of atrocities against Uighurs have the trappings of a Western regime-change operation. Rather than accept that states are always capable of such horrors against their people, the writers seem to think such accusations can only be part of a Western attempt at demonizing the Chinese state to, in their words, “advance imperial ambitions.” All of the information presented by Singh and Norton attacks the reputations of the media outlets and the human rights group (the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders, or CHRD) that have reported on the issue, but nothing gets at the factual basis. Contradicting their misinformed argument, China itself recently acknowledged the existence of the “re-education centers.” Multiple reports from people who have been able to flee describe the terrifying and apparently genocidal actions of the Chinese state (see here, here, and here).

Iran has a number of groups challenging its sovereignty on the physical extremes of its territory, namely in Baluchistan to the southeast and the Ahwazi Arabs in the southwest. At least one group, the Mujahideen e Khalq (MEK), is heavily supported by outside powers and US figures as a challenger to the Islamic Republic. In some cases, such support is illicit and hard to prove; in the case of Iran, many conservatives in the US openly agitate for changing the government’s leadership and support the MEK to take its place. Rudy Giuliani, one such conservative figure, spoke openly about seeing “…an end to the regime in Iran.” John Bolton is also affiliated with the group, speaking about how the MEK was ready to replace the Iranian regime. Indeed, such tactics come from a long and well-documented history of US attempts to interfere in foreign countries’ politics, especially during the Cold War, as part of the Communism “containment” policy. It is this history in Iran (1953), Iraq (1963), Afghanistan (1980), Chile (1973), El Salvador (1980s), Guatemala (1954), Nicaragua (1981-1986), Congo (1961) and most recently Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003)—examples I personally detest and do not justify or ignore—that anti-imperialists draw on today in labeling groups like ISIS and al-Qaeda not only as terrorists, but as puppets of imperialism—a step I cannot support, and which the facts do not support.

This is where the War on Terror discourse has come full circle, now pointed back at the US by anti-imperialists and states like Russia, Iran, and Syria. In Syria, the roots of the current civil war lie in the Arab Uprisings that began in late 2010. In line with the demands for more just rule, more freedoms, and an end to corruption, Syrians rose up peacefully demanding reforms from the authoritarian government in Damascus. Yet, to some, unfortunately, the entire series of Arab Uprisings looks like one big CIA conspiracy. Instead of a genuine popular uprising in Syria later co-opted by larger forces, the entire war is claimed by some to be a means to build an oil pipeline through Syria for Western interests. Iran’s Ayatollah Khamenei accused the US of being behind ISIS to distract the world from Israel. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov accused the US of moving ISIS fighters from Syria to Iraq and Afghanistan.

In this way, actual US foreign policy throughout the Cold War and the later invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan shape the worldview of anti-imperialists, making the logical leap to the US creating and funding ISIS possible. One need not deny or turn a blind eye to any of those parts of history to question the application of that discourse to our understanding of the war and crisis in Syria. Neither the McCain photo, nor any of the publicly available information proves that ISIS was formed deliberately by the US and Israel as part of their attempts to dominate the region, nor is there any evidence to suggest the US has been arming or helping ISIS. Making this point in no way necessitates supporting the foreign policy of the US or Israel. Rather, the available evidence suggests ISIS is a product of blowback, i.e., unforeseen consequences, from the failures of US foreign policy, but not a deliberate creation that the US manipulates like a puppet. The distinction is key. The former does not let the US off the hook for terrible foreign policy, but also does not wantonly accuse it of actions for which there is no evidence. The latter position, all too common among anti-imperialists, says more about their worldview—and their confused notion of what it really means to oppose imperialism—than it does about reality.